Mad About Memes … But is it Fair Use in Singapore?

This article assesses whether memes which are circulated on social media and the internet would be considered fair use or fair dealing under Singapore copyright law. It makes references to the decisions of the US Supreme Court and Circuit Courts in this area, and concludes that such memes generally are permissible transformative uses of the original works in a digital cultural milieu.

Introduction

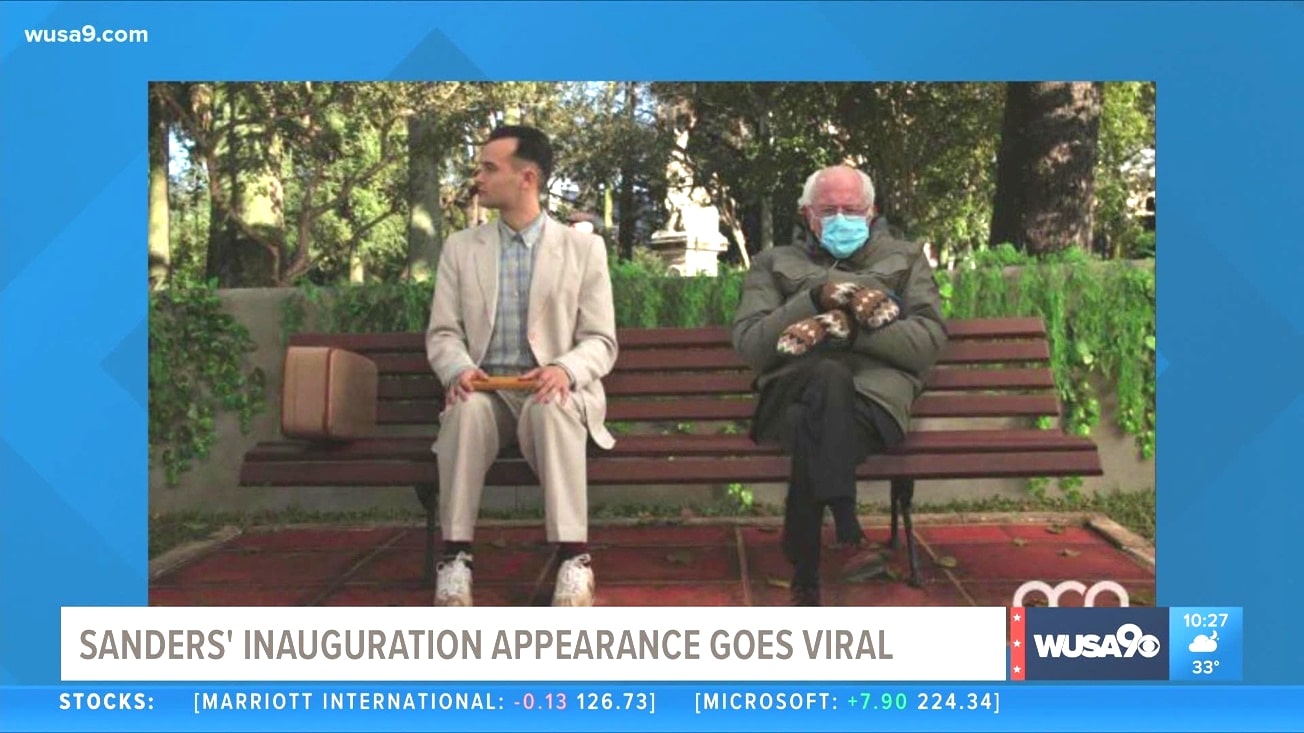

In January 2021, an internet meme took the world by storm. The photograph by Getty photographer Brendan Smialowski of Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, a former presidential candidate, sitting comfortably masked, cross-legged and bundled up in a bulky coat with garish oversized mittens, at President Joe Biden’s inauguration on 20 January 2021, captured the imagination of netizens as the image was inserted into a panoply of famous scenarios and everyday situations that include being on the USS Enterprise in Star Trek, at The Last Supper, sitting with Forrest Gump on a bench, and having a conference with the superhero group The Avengers.1Mike Ives and Daniel Victor, Bernie Sanders Is Once Again the Star of a Meme, The New York Times (Jan. 21, 2021) https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/21/us/politics/bernie-sanders-meme.html.

Memes provide a cogent example of how cultural expression shapes and is shaped by digital technology, demonstrating the constant challenge of reconciling social norms of online communication with the fair use doctrine in copyright law. Memes are a pervasive form of expression online and may incorporate image or video elements which are widely shared across a variety of internet platforms and social media apps. They often draw from copyrighted works of popular culture such as films, television series, paintings or photographs, and rely on the viewer’s prior knowledge to make the necessary semiotic connections. Ultimately, memes circulated on social media and the internet – collectively known as “digital memes” – may be conceived as remixed, iterated discursive units of digital culture typified by rapid diffusion that inhere some form of commentary.

Contemporary society has been described with terms such as “presentational cultural regime” and “specular economy.”2P. David Marshall, The Celebrity Persona Pandemic 5, 37 (2016); P. David Marshall, The Specular Economy: Celebrity, Two-Way Mirrors, and the Personalization of Renown, 47(6) Soc’y 498 (2010). These characterisations reflect how the influence of social media in the 21st century has led to new social norms of behaviour where individuals present themselves to others, whether physically or virtually, on various social media platforms and impels innovative economic models. Cultural norms of fair use in the digital realm vary greatly from the legal framework imposed by copyright law. The divergence of these norms is reinforced by a virtual absence of copyright enforcement against the private users that create digital memes. Insofar as the use of copyrighted works is concerned, private non-commercial individual internet users perceive that a “free culture” permeates the internet.3Mary W. S. Wong, Transformative User-Generated Content in Copyright Law: Infringing Derivative Works or Fair Use, 11 Vand. J. Ent. & Tech. L. 1075, 1081 (2009). If something is published online, such users often see no harm in reposting those works on different websites or social media platforms such as Instagram, Twitter or Facebook. This perceived free culture online naturally conflicts with copyright holders’ exclusive rights to control reproduction and distribution of their works. Ultimately, the seemingly permissionless nature of the internet and social media platforms, combined with the breakneck speed in which users can download, alter, and reshare content, have combined to create a semi-anarchic system where emergent norms constrain user behaviour to a greater extent than do legal and regulatory structures such as copyright law.

This article comments on how digital memes are protected by the fair use/fair dealing doctrine, and to what extent they should be, under Singapore copyright law, with references made to decisions of the United States (US) Supreme Court and Circuit Courts of Appeals.

Memes and Digital Culture

What are Memes?

The term “meme” was first introduced by biologist Richard Dawkins in his book The Selfish Gene in 1976.4Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene (1976). The word meme derives from the Greek mimema, meaning something which is imitated, which Dawkins shortened to rhyme with gene. Dawkins defined memes as a small cultural units of transmission, analogous to genes, which are spread from person to person by copying or imitation that include specific signifiers such as melodies, catchphrases and clothing fashions. According to Limor Shifman, like genes, memes are replicators that are constantly subject to variation, competition, selection, and retention.5Limor Shifman, Memes in a Digital World: Reconciling with a Conceptual Troublemaker, 18 J. Computer-Mediated Comm. 362, 363 (2013). As different memes compete with one another for attention, only those that are suited to their sociocultural environment are propagated quickly and successfully, i.e. going viral. Michele Knobel and Colin Lankshear contend that the word meme is employed by Internet users mainly to describe the rapid uptake and spread of a “particular idea presented as a written text, image, language ‘move’, or some other unit of cultural ‘stuff’.”6Michele Knobel and Colin Lankshear, A New Literacies Sampler 202 (2007).

Broadly speaking, digital culture is the interaction of people through computers and mobile devices. The term “digital culture” distinguishes from earlier forms of media and reflects new ways in which users interact with copyrighted works, including user-generated content, algorithmically curated newsfeeds, and the role of social media influencers. Ultimately, the digital realm is a readily available carnivalesque arena for individuals to express themselves and to make – and constantly remake – an online public persona. By posting, sharing, and creatively altering what they find online, social media users use readily available images, especially well-known images imbued with cultural meanings, to construct their public selves. The circulation of digital memes usually alter the meaning of the underlying works through semiotic recontextualisation, recoding, or visual editing, but they often do so in a way that does not mesh well with copyright law that is developed for dissemination of works through traditional intermediaries. Memes have become a fundamental mode of expression in digital culture, embodying the transformative qualities that fair use is intended to protect.

Digital memes defy rigid categorisation, but establishing a definition is necessary to analyse them through the lens of copyright law. Bradley Wiggins defines digital memes as:

“[a] remixed, iterated message that can be rapidly diffused by members of participatory digital culture for the purpose of satire, parody, critique, or other discursive activity. An internet meme is a more specific term for the various iterations it represents, such as image macro memes, GIFs, hashtags, video memes, and more. Its function is to posit an argument, visually, in order to commence, extend, counter, or influence a discourse.”7Bradley E. Wiggins, The Discursive Power of Memes in Digital Culture: Ideology, Semiotics, and Intertextuality 11 (2019).

In the propagation of digital memes, overt reproduction of the original image is often accompanied by new elements which may be images or text which introduces a different take on the original event.

Typology of Memes

For the purpose of copyright fair use analysis, memes may be grouped into three broad categories:8There is actually a fourth category of Self-referential or Standalone memes, which often utilise and remix crudely drawn characters that reference digital culture but they generally do not engage significant copyright concerns and will not be discussed in this article

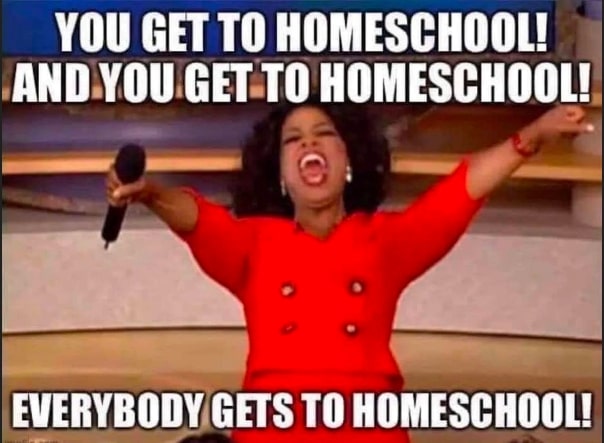

(1) Image Macros, which caption direct reproductions of existing visual and audiovisual works for commentative effect and vary to the extent they alter the underlying meaning or message of the original work;9An example is the Oprah’s You Get A Car Meme. Know Your Meme, “Oprah’s ‘You Get a Car’”, Online: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/oprahs-you-get-a-car.

(2) Exploitables, which rely on direct reproductions of works as a single frame or series of frames in which users can add dialogue or label objects within the frame to explicate a relationship between objects and subjects;10An example is the Distracted Boyfriend Meme. Know Your Meme, “Distracted Boyfriend”, Online: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/distracted-boyfriend.

(3) Edits, which visually transform original works by adding elements into existing scenes or relocating subjects into unfamiliar or ironic surroundings.11A recent example is the Bernie Meme. Know Your Meme, “Bernie Sanders Wearing Mittens Sitting in a Chair”, Online: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/bernie-sanders-wearing-mittens-sitting-in-a-chair. Another example is the Rihanna Met Gala Dress Meme. Know Your Meme, “Rhianna’s Met Gala Dress”, Online: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/rihannas-met-gala-dress.

The first two categories either directly reproduce or allow easy modification to the underlying image requiring few technical skills that the average private user could easily grasp, while the third can be executed with widely available software such as Photoshop.

Image Macros – perhaps the most common type of memes – encompass a spectrum of captioned direct reproductions of copyrighted works ranging from those that transform the message or meaning of the original work with some degree of social commentary, to “reaction images” which are instead used to augment the user’s own expression. Many draw upon current events and recent works of popular culture, sometimes captioning an image only through an online platform’s user interface. While utilising a still image from an audiovisual work or photograph for purposes of self-expression rather than to entertain or to inform arguably does alter the purpose of the use from the original, those that use the format to create new information, insights, and understandings will have a greater claim to transformativeness than reaction images.

Exploitable memes reproduce a single frame or multiple frames from a photo or audiovisual work as a template, differing from Image Macros in that they label subjects or objects in the frame to explicate a relationship between elements in the frame, or to create a dialogue between two characters. The visual relationship between objects or subjects in the frame allow meme creators to discuss other concepts, often wholly unrelated to the original scene. By labelling subjects in the frame, meme creators leverage one’s understanding of the visual relationship between characters to suggest an analogous relationship in another form.

Edits are a highly creative and varied category of memes in which users add elements to existing scenes or remove characters from their original context. Often drawing from audiovisual works and photographs taken of notable people, they represent a more labor-intensive form of memes which creates new aesthetics and visually alters works in ways that are more immediately cognisable under transformative use doctrine. They are also generally the category that comes closest to parody, as a prominent element – or the “heart” – of the original image necessarily becomes the object of ridicule or derision.

The typology groups memes based on the use they make of the underlying work, offering enough precision to apply the fair use factors to each category. While Edits bear analogy to cases involving appropriation artists such as Richard Prince and Jeff Koons, Image Macros and Exploitable memes rely on a form of semiotic play that could be understood as the “creation of new information, new aesthetics, new insights and understandings” that may “reasonably be perceived” by the online community, but requires a comparison between the author’s intent and the supposed alteration to that intent by the secondary user.12See Blanch v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244 (2nd Cir. 2006); Cariou v. Prince, 714 F.3d 694 (2nd Cir. 2013). Memes that recode and recontextualise the original work without visual alteration are harder to situate within existing fair use doctrines than those that visibly transform an underlying work. An internet meme can only exist if it refers to something in addition to the original subject matter it contains, existing as an inherently intertextual medium that draws upon the semiotic aura of the original work. Most works are indirectly intertextual by adherence to a genre, or directly by way of citation, allusions, parody, pastiche, etc., but memes often directly appropriate earlier expressions to draw upon their cultural symbolic relevance, relying on the audience’s widespread familiarity and relatability with underlying content to emphasise their message.13Kara Podraza, When Is a Little Too Much: The De Minimis Doctrine and Its Implications for Online Communication Tools, 25 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 550 (2018).

Fair Use / Fair Dealing in Singapore

Copyright law is intended to promote creativity and innovation by providing fair compensation to copyright holders. However, the exclusive rights of the copyright holder give way to a user’s right allowing limited, unauthorised use of protected works to prevent these rights from stifling creativity and innovation.

Those familiar with Singapore copyright law will know that we can currently rely on the open-ended fair dealing defence under section 35(1) of the Copyright Act, which recognises fair dealing for “any purpose” other than those referred to in section 36 (for the purpose of criticism or review), and section 37 (for the purpose of reporting current events). Section 35(2) then provides a non-exhaustive list of factors to be considered – and balanced – in the determination of whether a particular dealing are fair. In this regard, the Court of Appeal in Global Yellow Pages v Promedia Directories Pte Ltd has provided significant guidance on the interpretation these factors.14(2017) 2 SLR 185 (“Global Yellow Pages”). Section 35(2) in full provides:

“For the purposes of this Act, the matters to which regard shall be had, in determining whether a dealing with a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work or with an adaptation of a literary, dramatic or musical work, being a dealing by way of copying the whole or a part of the work or adaptation, constitutes fair dealing with the work or adaptation for any purpose other than a purpose referred to in section 36 or 37 shall include —

(a) the purpose and character of the dealing, including whether such dealing is of a commercial nature or is for non-profit educational purposes;

(b) the nature of the work or adaptation;

(c) the amount and substantiality of the part copied taken in relation to the whole work or adaptation;

(d) the effect of the dealing upon the potential market for, or value of, the work or adaptation; and

(e) the possibility of obtaining the work or adaptation within a reasonable time at an ordinary commercial price.”

The Copyright Bill 2021 contains a new section 182(1) which will replace the current section 35, and it emphatically states that “[a] fair use of any work is a permitted use.”15See Copyright Bill 2021, s 182(2) (“A fair use of a protected performance is a permitted use.”). Section 183 retains the first four factors from the present section 35(2) as the factors to be considered in deciding whether a work or performance is fairly used.

In Global Yellow Pages, the Court of Appeal traced the development of fair dealing in Singapore, as codified in the Copyright Act. The Court noted that in 2004, the scope of section 35 was expanded such that a fair dealing for “any purpose” (as opposed to merely for “research or private study”) might be held not to amount to an infringement of copyright, and that “[t]his also made Singapore’s fair dealing provisions more similar to its American counterpart, which is more open-textured.”16Global Yellow Pages (2017) 2 SLR 185 at (76). The Court emphasised that the inquiry under s 35(2), “in the final analysis, is necessarily fact-sensitive.”17Ibid at (86). Section 35(2) enumerates five non-exhaustive fair dealing factors to be considered; four are similar to the US fair use factors, the fifth requires a consideration of “the possibility of obtaining the work or adaptation within a reasonable time at an ordinary commercial price”. Chief Justice Menon hinted at the willingness of the local courts to take greater cognisance of American and Australian decisions in this area.18Ibid at (76). The persuasiveness and relevance of US fair use decisions was similarly argued in earlier academic articles.19David Tan and Benjamin Foo, “The Unbearable Lightness of Fair Dealing: Towards an Autochthonous Approach in Singapore” (2016) 28 SAcLJ 124; David Tan, “The Transformative Use Doctrine and Fair Dealing in Singapore: Understanding the ‘Purpose and Character’ of Appropriation Art” (2012) 24 SAcLJ 832.

In particular, in respect of the first factor, the purpose and character of the dealing, Menon CJ emphasised that “the inquiry is heavily shaped by what it was in a work that attracted copyright and what was done with that aspect of the work.”20Global Yellow Pages (2017) 2 SLR 185 at (77). The Court referred to both English and American cases, observing that this factor favoured fair dealing where “the defendant added to, recontextualised or transformed the parts taken”21Ibid at (79) (referring to Newspaper Licensing Agency v Marks & Spencer plc (1999) EMLR 369 at 380; University of London Press Ltd v University Tutorial Press Ltd (1916) 2 Ch 601 at 613-614). or where the new work was “transformative”, i.e. whether it “supersede[s] the objects” of the original creation, or “adds something new, with a further purpose or different character”.22Ibid (referring to Campbell v Acuff-Rose Music, Inc, 510 US 569 (1994) (“Campbell”)). It appears that the Court of Appeal is edging toward the view of the US Supreme Court in Campbell v Acuff-Rose Music, Inc when Menon CJ remarked that “we do not go as far as those cases which suggest that a commercial nature or purpose of the dealing will presumptively be regarded as unfair” and “the commerciality of the dealing is but one of the factors to be considered and it will not necessarily be fatal to a finding of fair dealing.”23Ibid at (81). In fact the Court considered the application of the transformative use doctrine in Campbell (where the commerciality of the rap song “Pretty Woman” was trumped by the transformative value of the parody) and in Authors Guild v Google Inc24Authors Guild v Google, Inc, 804 F 3d 202 (2nd Cir, 2015). (where Google’s making of digital copies of books for the purpose of enabling a search for identification of books containing a term of interest to the searcher involved a highly transformative purpose).

Interestingly, the Court of Appeal made a reference that “various circuits were apparently split”25Global Yellow Pages (2017) 2 SLR 185 at (88). on the transformative use doctrine, but unfortunately, the Court did not explain further the extent to which it would accept the transformative use doctrine as informing Singapore law. The transformative use test has become the defining standard for fair use, and it has risen to the top of the agenda of the copyright academic community in the United States in the last five years. In light of the US Supreme Court’s decision in Google LLC v Oracle America Inc handed down in April 2021, the transformative use doctrine has taken a backseat in respect of the fourth factor which evaluates market impact.26Google LLC v Oracle America Inc, 141 S Ct 1183 (2021) (“Google”). Justice Breyer, delivering the majority’s opinion, held that: “in determining whether a use is “transformative,” we must go further and examine the copying’s more specifically described “purpose[s]” and “character.””27Ibid at 1203. Furthermore, the Court would “take into account the public benefits the copying will likely produce.”28Ibid at 1206. The majority concluded that since Google had reimplemented a user interface, taking only what was needed to allow users to put their accrued talents to work in a new and transformative program, its copying of the Sun Java API was a fair use of the material.

The second factor, the nature of the work, recognises that some works are closer to the core of intended copyright protection than others, especially literary, dramatic, musical and artistic (LDMA) works that are highly creative in nature.29Staniforth Ricketson and Christopher Creswell, The Law of Intellectual Property: Copyright, Designs and Confidential Information, 2nd ed. (Lawbook Co, 2002). This factor tends to weigh against fair use when LDMA works are being copied. As for the third factor, the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work, it asks whether the quantity and value of the materials used are reasonable in relation to the purpose of the copying.30Global Yellow Pages (2017) 2 SLR 185 at (83). Nonetheless, there is no blanket rule against copying entire works where such copying is reasonably necessary.31For the US position, see Cariou v Prince 714 F 3d 694 at 710 (2nd Cir. 2013), citing Bill Graham Archives v Dorling Kindersley Ltd 448 F 3d 605 at 613 (2nd Cir, 2006): “Although neither our court nor any of our sister circuits has ever ruled that the copying of an entire work favours fair use, … courts have concluded that such copying does not necessarily weigh against fair use because copying the entirety of a work is sometimes necessary to make a fair use of the image. The third-factor inquiry must take into account that the extent of permissible copying varies with the purpose and character of the use” (emphasis added).

The third factor also influences the fourth factor, which investigates the effect of the use of original work on the potential market on the value of the copyrighted work. This requires the court to consider “not only the extent of market harm caused by” the alleged infringer’s action, but also whether the defendant’s conduct, if “unrestricted and widespread”, would “result in a substantially adverse impact on the potential market” for the original; it takes into account not only harm to the original but also harm to the market for derivatives works.32Global Yellow Pages (2017) 2 SLR 185 at (84). The fourth factor generally seeks to uphold the incentive rationale that underpins copyright law by preventing unjust enrichment and harm to the original works, thereby “facilitat[ing] greater investment, research and development in copyright industries in Singapore.”33Parliamentary Debates Singapore: Official Report, vol 78 col 1053 (16 November 2004) at col. 1052 (Parliament commissioned a study which considered jurisdictions including the UK, Australia, Canada, Germany, France and the United States.) This fourth factor is influenced by the degree of transformative use present under the first factor; a finding of a highly transformative use will result likely a finding of little or no market substitution, and market harm will not so readily inferred. However, where there is moderate or little transformative use, the greater the quantity or quality taken (third factor) may indicate that the secondary work serves as a market substitute, with the fourth factor thus weighing against fair use. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals in TCA Corp. v. McCollum has commented that the generous view of what might constitute transformative use (and therefore fair use) might have hit its “high-water mark” in Cariou,34TCA Corp. v. McCollum, 839 F.3d at 181. Judge Easterbrook of the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals was also highly critical of the Cariou decision: Kienitz v. Sconnie Nation, LLC, 766 F.3d 756, 758 (7th Cir. 2014) (“We’re skeptical of Cariou’s approach, because asking exclusively whether something is “transformative” not only replaces the list in § 107 but also could override 17 U.S.C. § 106(2), which protects derivative works”). and Judge Pierre Leval, now sitting on the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, has retreated noticeably from endorsing the transformative use talisman in Capitol Records, LLC v. ReDigi, Inc. commenting that the fourth factor is “undoubtedly the single most important element of fair use.”35910 F.3d 649, 662 (2nd Cir, 2018) (citing Harper & Row Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises, 471 U.S. 539, 566 (1985)). he correctly observed that the fourth factor is a consideration of whether the secondary use brings a competing substitute to the marketplace, and “the more the objective of the secondary use differs from the original, the less likely it will be to supplant the commercial market for the original.”36 Capitol Records LLC v ReDigi Inc, 910 F.3d 649, 662 (2nd Cir, 2018) (internal citations omitted). The renaissance of the primacy of the fourth factor was alluded to in the majority’s judgment of the Supreme Court in Google,37Google, 141 S Ct 1183, 1206-9 (2021) and more forcefully emphasised in the dissenting judgment.38Ibid at 1216.

Finally, the fourth factor possibly influences the fifth factor in section 35(2), which evaluates the possibility of obtaining the work within a reasonable time at an ordinary commercial price.39See generally, Global Yellow Pages (2017) 2 SLR 185 at (35); Tan & Foo, supra note 18, at (44)-(47). Essentially, if the defendant could have obtained the work on reasonable commercial terms, then this factor weighs against fair use. The fifth factor, however, will no longer be relevant as Proposal 6 of the Copyright Review Report has recommended the removal of the final factor, in order to “mirror more closely in form”40Ministry of Law and IPOS, Singapore Copyright Review Report (17 January 2019) at (2.6.8), https://www.mlaw.gov.sg/files/news/public-consultations/2021/copyrightbill/Annex_A-Copyright_Report2019.pdf. the US fair use provision that only consists of the first four factors. This has also been affirmed in section 183 of the Copyright Bill where this factor has been removed.

In summary, while the talismanic power of the transformative use doctrine appeared to have diminished by 2021, it has not been discredited by the Supreme Court in Google. One would expect courts in Singapore to place greater weight on the substitution effects or effects on potential derivative and licensing markets that a secondary use impinges on. Moving forward, transformative use as a juridical concept is unlikely to have the trump effect which it has enjoyed for over the last three decades.

Are Memes Circulated on Social Media Fair Use?

The digital culture has led to a pronounced focus on the production of the self or an online persona – whether through Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Twitter, or Pinterest, billions of individuals worldwide are constantly making and remaking public versions of themselves for myriad purposes and monitoring these profiles daily. As the COVID-19 pandemic ravaged the world and governments enforced draconian lockdown measures, individuals have stormed social media to express their frustration, anger, and despair. The proliferation of memes on Twitter and Facebook, and parody videos on YouTube provide humorous outlets to convey our emotions and criticisms of political leaders and government agencies in their handling of the pandemic. Images and videos are widely shared and reposted, often at breakneck speed.

The posting of selfies, social photographs, and memes all form “part of an ongoing communication of who you are, what you are experiencing, the simple fact that you exist and are live doing things.”41Nathan Jurgenson, The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media 16 (2019). A well-known literary or artistic work does much more than simply educate, inform or entertain; it also functions as a signifier of a set of social meanings. Digital memes remix and recode images and videos with meanings often substantially different from the original expression. They result from a process of audience interaction and participation with some of the most prevalent and salient cultural forms available to the public.

Image Macro memes usually manifest a substantially different purpose than the original. Image Macro memes, as exemplified by the Oprah You Get A Car memes, as well as Exploitable memes such as the Distracted Boyfriend memes, represent non-visually transformative uses that utilise the underlying work as “raw material” for the different purposes of political, social, and cultural expressions. Current fair use jurisprudence applies most unproblematically to Edits, in which visual transformation alters or recontextualises key elements in the frame to suit the secondary user’s discursive intent, such as the Bernie Sanders Wearing Mittens Sitting In A Chair memes. Memes that are focused on the creation of shared meanings by commenting on relatable and broadly applicable socio-political themes largely external to the self (such as the coronavirus pandemic, the presidential election or #blacklivesmatter), and “reaction image”-style memes are simply different aspects of individual expression that enables users to construct and promote their idealised digital persona through identification with the semiotic coding of the original work. By utilising well-known characters or works to portray their emotions or reactions rather than a selfie or photo of themselves, individuals leverage the near-universal semiotic coding and instantly-recognisable features of the original – at the same time reinforcing that individual’s role as a participant in a mediated digital culture. Denying meme creators – especially if they were private non-commercial individuals – protection under fair use risks further impoverishing the cultural public domain and subjecting social media users to copyright infringement liability or harassment by rights owners.

Digital memes tend to be highly transformative under the first factor, thus reducing their relevant fourth factor market impacts. While there is a recent reinvigoration of the fourth factor in the US Supreme Court and Circuit Courts, neither this factor nor any arguably commercial character of the user would seem capable of outweighing the transformativeness of these categories of memes. Memes neither create a market substitute for the original nor infringe directly on the exclusive rights to authorise derivative works, as no real licensing market exists for memes. For instance, the Oprah memes do not produce a market alternative for Oprah’s talk show, or is there any evidence that the increased exposure of her car giveaway led to any relevant market harms for the copyright in The Oprah Winfrey Show.

Conclusion

Social media today invariably enable and encourage the creation of individuated online identities through repetition, reproduction, and remixing. Unsurprisingly, we are mad about memes! The memes circulated on social media, with their rich semiotic connotations, are popularly used for the purpose of creating, maintaining and remaking of a digital public persona, and should generally qualify as highly transformative secondary uses that repurpose copyrighted works in an online medium. This article does not contend that there should be a per se rule that all digital memes are fair use. Fair use ought to be found for most private individuals using memes, but the finding may not be as certain for influencers on social media who gain a commercial benefit from their social media account or for multinational corporations seeking to capitalise on popular iconic works for profit.

Endnotes

| ↑1 | Mike Ives and Daniel Victor, Bernie Sanders Is Once Again the Star of a Meme, The New York Times (Jan. 21, 2021) https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/21/us/politics/bernie-sanders-meme.html. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | P. David Marshall, The Celebrity Persona Pandemic 5, 37 (2016); P. David Marshall, The Specular Economy: Celebrity, Two-Way Mirrors, and the Personalization of Renown, 47(6) Soc’y 498 (2010). |

| ↑3 | Mary W. S. Wong, Transformative User-Generated Content in Copyright Law: Infringing Derivative Works or Fair Use, 11 Vand. J. Ent. & Tech. L. 1075, 1081 (2009). |

| ↑4 | Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene (1976). |

| ↑5 | Limor Shifman, Memes in a Digital World: Reconciling with a Conceptual Troublemaker, 18 J. Computer-Mediated Comm. 362, 363 (2013). |

| ↑6 | Michele Knobel and Colin Lankshear, A New Literacies Sampler 202 (2007). |

| ↑7 | Bradley E. Wiggins, The Discursive Power of Memes in Digital Culture: Ideology, Semiotics, and Intertextuality 11 (2019). |

| ↑8 | There is actually a fourth category of Self-referential or Standalone memes, which often utilise and remix crudely drawn characters that reference digital culture but they generally do not engage significant copyright concerns and will not be discussed in this article |

| ↑9 | An example is the Oprah’s You Get A Car Meme. Know Your Meme, “Oprah’s ‘You Get a Car’”, Online: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/oprahs-you-get-a-car. |

| ↑10 | An example is the Distracted Boyfriend Meme. Know Your Meme, “Distracted Boyfriend”, Online: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/distracted-boyfriend. |

| ↑11 | A recent example is the Bernie Meme. Know Your Meme, “Bernie Sanders Wearing Mittens Sitting in a Chair”, Online: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/bernie-sanders-wearing-mittens-sitting-in-a-chair. Another example is the Rihanna Met Gala Dress Meme. Know Your Meme, “Rhianna’s Met Gala Dress”, Online: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/rihannas-met-gala-dress. |

| ↑12 | See Blanch v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244 (2nd Cir. 2006); Cariou v. Prince, 714 F.3d 694 (2nd Cir. 2013). |

| ↑13 | Kara Podraza, When Is a Little Too Much: The De Minimis Doctrine and Its Implications for Online Communication Tools, 25 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 550 (2018). |

| ↑14 | (2017) 2 SLR 185 (“Global Yellow Pages”). |

| ↑15 | See Copyright Bill 2021, s 182(2) (“A fair use of a protected performance is a permitted use.”). |

| ↑16 | Global Yellow Pages (2017) 2 SLR 185 at (76). |

| ↑17 | Ibid at (86). Section 35(2) enumerates five non-exhaustive fair dealing factors to be considered; four are similar to the US fair use factors, the fifth requires a consideration of “the possibility of obtaining the work or adaptation within a reasonable time at an ordinary commercial price”. |

| ↑18 | Ibid at (76). |

| ↑19 | David Tan and Benjamin Foo, “The Unbearable Lightness of Fair Dealing: Towards an Autochthonous Approach in Singapore” (2016) 28 SAcLJ 124; David Tan, “The Transformative Use Doctrine and Fair Dealing in Singapore: Understanding the ‘Purpose and Character’ of Appropriation Art” (2012) 24 SAcLJ 832. |

| ↑20 | Global Yellow Pages (2017) 2 SLR 185 at (77). |

| ↑21 | Ibid at (79) (referring to Newspaper Licensing Agency v Marks & Spencer plc (1999) EMLR 369 at 380; University of London Press Ltd v University Tutorial Press Ltd (1916) 2 Ch 601 at 613-614). |

| ↑22 | Ibid (referring to Campbell v Acuff-Rose Music, Inc, 510 US 569 (1994) (“Campbell”)). |

| ↑23 | Ibid at (81). |

| ↑24 | Authors Guild v Google, Inc, 804 F 3d 202 (2nd Cir, 2015). |

| ↑25 | Global Yellow Pages (2017) 2 SLR 185 at (88). |

| ↑26 | Google LLC v Oracle America Inc, 141 S Ct 1183 (2021) (“Google”). |

| ↑27 | Ibid at 1203. |

| ↑28 | Ibid at 1206. |

| ↑29 | Staniforth Ricketson and Christopher Creswell, The Law of Intellectual Property: Copyright, Designs and Confidential Information, 2nd ed. (Lawbook Co, 2002). |

| ↑30 | Global Yellow Pages (2017) 2 SLR 185 at (83). |

| ↑31 | For the US position, see Cariou v Prince 714 F 3d 694 at 710 (2nd Cir. 2013), citing Bill Graham Archives v Dorling Kindersley Ltd 448 F 3d 605 at 613 (2nd Cir, 2006): “Although neither our court nor any of our sister circuits has ever ruled that the copying of an entire work favours fair use, … courts have concluded that such copying does not necessarily weigh against fair use because copying the entirety of a work is sometimes necessary to make a fair use of the image. The third-factor inquiry must take into account that the extent of permissible copying varies with the purpose and character of the use” (emphasis added). |

| ↑32 | Global Yellow Pages (2017) 2 SLR 185 at (84). |

| ↑33 | Parliamentary Debates Singapore: Official Report, vol 78 col 1053 (16 November 2004) at col. 1052 (Parliament commissioned a study which considered jurisdictions including the UK, Australia, Canada, Germany, France and the United States.) |

| ↑34 | TCA Corp. v. McCollum, 839 F.3d at 181. Judge Easterbrook of the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals was also highly critical of the Cariou decision: Kienitz v. Sconnie Nation, LLC, 766 F.3d 756, 758 (7th Cir. 2014) (“We’re skeptical of Cariou’s approach, because asking exclusively whether something is “transformative” not only replaces the list in § 107 but also could override 17 U.S.C. § 106(2), which protects derivative works”). |

| ↑35 | 910 F.3d 649, 662 (2nd Cir, 2018) (citing Harper & Row Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises, 471 U.S. 539, 566 (1985)). |

| ↑36 | Capitol Records LLC v ReDigi Inc, 910 F.3d 649, 662 (2nd Cir, 2018) (internal citations omitted). |

| ↑37 | Google, 141 S Ct 1183, 1206-9 (2021) |

| ↑38 | Ibid at 1216. |

| ↑39 | See generally, Global Yellow Pages (2017) 2 SLR 185 at (35); Tan & Foo, supra note 18, at (44)-(47). |

| ↑40 | Ministry of Law and IPOS, Singapore Copyright Review Report (17 January 2019) at (2.6.8), https://www.mlaw.gov.sg/files/news/public-consultations/2021/copyrightbill/Annex_A-Copyright_Report2019.pdf. |

| ↑41 | Nathan Jurgenson, The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media 16 (2019). |