The Role of Prosecutors as Ministers of Justice

Disclosure of Unused Material, and Calling of Witnesses at Trial (Part I)

This two-part article examines two aspects intimately related to a prosecutor’s role as a Minister of Justice – the Prosecution’s duty to disclose unused material, and its discretion to call witnesses at trial. This part offers a summary of the current law in Singapore on the Prosecution’s duty to disclose unused material, a discussion of why there will be cases where the Prosecution assesses its disclosure obligations differently from the courts, and some general suggestions on how to further enhance matters moving forward. The other part (forthcoming in next month’s issue) considers recent case law developments vis-à-vis the Prosecution’s discretion to call witnesses at trial, as well as some challenging questions that these particular developments potentially raise.

Introduction

Prosecutors around the world, including here in Singapore, have been regarded as Ministers of Justices in the criminal justice system. One main reason they are so called is because of the pivotal role they play in assisting fact finders (whether courts or juries) to ascertain the truth and effecting justice, when an accused claims trial to committing an offence.1See, for example, Justice Steven Chong, “The role and duties of a prosecutor – the lawyer who never ‘loses’ a case, whether conviction or acquittal” (10 November 2011) at (8), <https://www.supremecourt.gov.sg/Data/Editor/Documents/J%20Steven%20Chong%20Speeches/The%20Role%20and%20Duties%20of%20a%20Prosecutor%20(10.11.11).pdf>, Chief Justice Murrell, “Prosecutors as Ministers of Justice – Speech delivered at the inaugural annual ACT DPP Dinner” (2 August 2019), <https://courts.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/1396270/Speech-Prosecutors-as-ministers-for-justice.pdf>, Howard Shapray, “The Prosecutor as a Minister of Justice: a Critical Appraisal” (1969) 15 McGill Law Journal 124.

This previous decade has seen considerable developments in Singapore in two specific aspects intimately related to this role – first, the Prosecution’s duty to disclose evidence which it has in its possession but which it does not intend to admit as part of its case at trial (commonly known as “Prosecution unused material”), and second, the Prosecution’s discretion to call witnesses at a trial.2One of the most comprehensive study done on the role of prosecutors as Ministers of Justice and the two related aspects of the role in England and Australia is David Plater’s PhD thesis “The Changing Role of the Modern Prosecutor: Has the Notion of the ‘Minister of Justice’ Outlived its Usefulness” (April 2011), <https://eprints.utas.edu.au/10743/2/David_Plater_whole.pdf> (“Changing Role of the Modern Prosecutor”). This author fully commends this magisterial work to interested readers. All of these developments have been, and continue to be an integral part of the continuing progress and maturity of our criminal justice system.

This part of this article considers the duty to disclose unused material. In particular, it offers: a) a summary of the current law in this area in Singapore, which comprises statutory and common law obligations depending on the type of unused material in question, b) a discussion, with the full benefit of hindsight, on why there will be cases where the Prosecution assesses its disclosure obligations differently from the courts, despite prosecutors having exercised all due diligence and good faith in assessing, and c) some broad suggestions on how to further enhance matters moving forward

Duty to Disclose Unused Material

Current Law

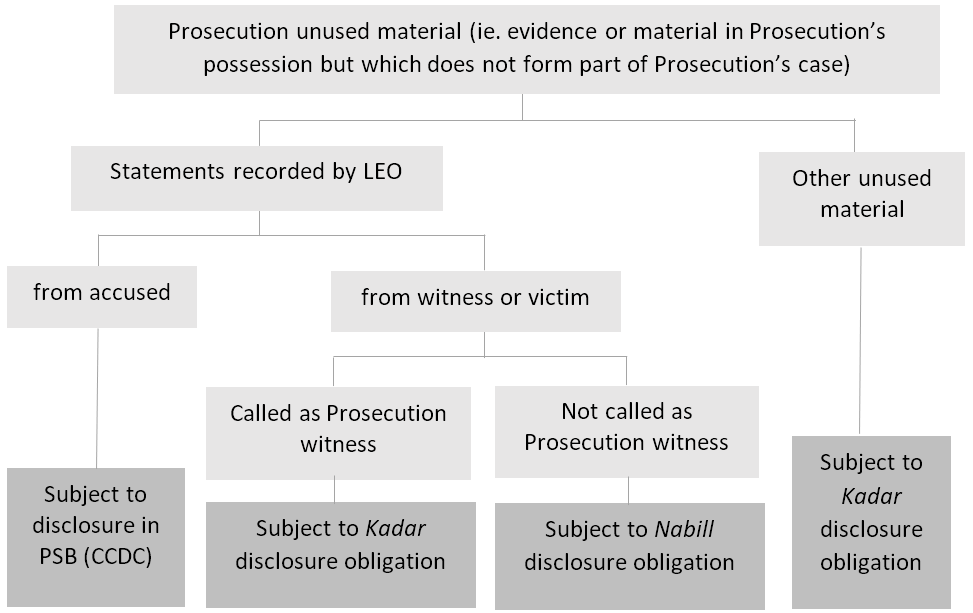

The current law in Singapore on prosecutors’ duty to disclose unused material can be quite readily stated. It comprises of three sub-components, and which is applicable, broadly speaking, turns on which type of unused material is being considered.

The first component is based on the Criminal Case Disclosure Conference (CCDC) scheme, which was introduced as part of the overhaul of our Criminal Procedure Code (CPC)3Cap 68, 2012 Rev Ed, Parts IX and X. ten years ago in 2010. Simply put, in a case where an accused claims trial to his charge(s) and his case falls under the scheme, the Prosecution will first have to extend to the accused the Case for the Prosecution. This includes the charge(s) against the accused, a summary of the facts in support of the charge(s), and statements from the accused recorded by a law enforcement officer (LEO), which the Prosecution intends to adduce as part of its case at trial.4Ibid, s 162(1). In exchange, the Defence has to provide its Case for the Defence, which includes a summary of his defence to the charge(s) and the supporting facts.5Ibid, s 165(1). The Prosecution must then disclose to the Defence in what is colloquially known as the Prosecution’s Supplementary Bundle (PSB), among other things, all other statements given by the accused to a LEO but which the Prosecution does not intend to adduce as part of its case at trial.6Ibid, s 166(1). These statements are one type of Prosecution unused material.

The second component arises from the 2011 Court of Appeal case of Muhammad bin Kadar v PP (Kadar).7(2011) 3 SLR 1205. See also Muhammad bin Kadar v PP (2011) 4 SLR 791, where the Prosecution sought clarification from the court on whether its duty to disclose extended to calling for and scrutinising material pertaining to the case that it had not already been made aware of. There, the Court held that the Prosecution has a common law duty to disclose to the Defence any unused material it has in its possession, which takes the following form (and which is not already subject to disclosure under the CCDC scheme):8Ibid at (113)-(116).

- any unused material that is likely to be admissible and that might reasonably be regarded as credible and relevant to the guilt or innocence of the accused, and

- any unused material that is likely to be inadmissible, but would provide a real (not fanciful) chance of pursuing a line of inquiry that leads to material that is likely to be admissible and that might reasonably be regarded as credible and relevant to the guilt or innocence of the accused.

The court elaborated that “might reasonably” means prima facie from an objective perspective and that prima facie in this specific context connotes a higher threshold than just a possibility. The Court added in summary that the duty does not apply to material which is neutral or adverse to the accused, but includes only material that tends to undermine the Prosecution’s case or strengthen the Defence’s case. Notably, this duty (Kadar disclosure obligation), requires a prosecutor to undertake a multi-layered assessment of various aspects of an unused material such as its admissibility and credibility, as well as whether it is favourable, neutral or adverse to the Prosecution and Defence’s case. Disclosure under this obligation should also generally be carried out before the trial begins,9Ibid at (113). and a failure to discharge this duty may cause a conviction to be overturned.10Ibid at (120).

The third component is based on the very recent Court of Appeal case of Muhammad Nabill bin Mohd Faud v PP (Nabill).11(2020) 1 SLR 984. In that case, the Court held that the Prosecution has an additional common law duty to disclose to the Defence a statement (or part(s) of a statement) given by a material witness and recorded by a LEO, where that witness is not a Prosecution witness at trial (Nabill disclosure obligation).12Ibid at (39). In that relation, a material witness refers to a witness who can be expected to confirm or contradict an accused’s defence in material respects.13Ibid at (4). Disclosure under this obligation should likewise generally take place before the trial begins.14Ibid at (50). Prior to this case, such statements would have been governed by the Kadar disclosure obligation.

As noted by the Court, both common law disclosure obligations are subject to any exception for non-disclosure recognised by law,15Ibid at (42). but there are also important differences between them.16Ibid at (41). Quite apart from the Nabill disclosure obligation applying only to a specific type of unused material, that obligation also does not require prosecutors to assess the admissibility and credibility of that material, nor whether it is favourable, neutral or adverse to the Defence. In that sense, the assessment is unidimensional, in that disclosure is required of any statement from a non-Prosecution witness who can be expected to confirm or contradict the Defence’s case in some relevant way. Separately, the Court left open the question of disclosure of material statements from Prosecution witnesses, but added that there is no reason why such statements should not (as a default) be subject to the Kadar disclosure obligation.17Ibid at (54)-(56).

Accordingly, the applicable test for prosecutors’ duty to disclose unused material now depends on which type of unused material is under consideration. Where the CCDC scheme applies, the general position may be summarised as such in the following diagram:

Diagram 1

Practical Challenges to Always Correctly Complying with Disclosure Obligations

At a general philosophical level, there is little doubt that the courts, the Prosecution and other lawmakers are in agreement that prosecutors, as Ministers of Justice, play a central role in ensuring all relevant material is placed before the Court to assist it in its determination of the truth. But as the courts and lawmakers have consistently and rightly recognised as well, in formulating the actual rules governing the Prosecution’s role, there is also need to have regard to the practical realities prosecutors face, and an appropriate balance should be struck.18See, for example, Kadar, supra n 7 at (86), Nabill, supra n 11 at (41(b)),

With the full advantage of hindsight, it is now possible to suggest some of the key practical challenges that prosecutors may face in trying to correctly assess and carry out its duty to disclose unused material, in particular its Kadar disclosure obligations, in every case.

Main sources of practical challenges

Given the limited space, only two main sources of potential challenge are discussed here. The first source is the fact that as mentioned above, the Kadar test requires prosecutors to engage in a multi-layered assessment of different dimensions of an unused material – its admissibility, credibility and relevance, each at a stipulated threshold, and these concepts and thresholds are inherently technical and complex, and all of which perforce come with some measure of vagueness. In this regard, three observations may be offered:

- Admissibility, for instance, is notoriously known as a difficult concept.19Chen Siyuan, “The Prosecution’s Duty of Disclosure in Singapore: Muhammad Bin Kadar v Public Prosecutor (2011) 3 SLR 1205” (2011) 11(2) Oxford University Commonwealth Law Journal 207 at 213-214 and Denise Wong, “Discovering the Right to Criminal Disclosure” (2013) 25 SAcLJ 548 at (74). One often has to navigate a web of complex evidence rules (and case law) to try and assess whether a piece of evidence is admissible. Credibility or reliability of a piece of real, documentary or testimonial evidence is also something which reasonable persons may come to different conclusions on. It is thus not at all out of place that the Prosecution, trial court and appellate court at times assess admissibility and reliability of a piece of evidence differently, despite all acting in good faith.20See, for example, Gopu Jaya Raman v PP (2018) 1 SLR 499.

- Moreover, any difficulty is compounded by the fact that prosecutors are to assess these aspects of a piece of unused material at a specific threshold (“might reasonably”, “likely” etc), which may be hard to ascertain with sufficient precision what they mean in practice.21Timothy Endicott, Vagueness in Law (Oxford University Press, 2000) at 50. For instance, although the court in Kadar equated “might reasonably” with the “prima facie” test, and also stated that these impose a higher threshold than just “a possibility”, practically speaking, it is by no means easy to see where or how the line should be drawn.

- Furthermore, while the Court in Kadar made known that prosecutors should assess objectively whether an unused material might reasonably be credible and relevant to the guilt or innocence of the accused, it was not stated whether that refers to a fully objective test, that is, from the perspective of a hypothetical “average” defence counsel, or that it is an objective-subjective test, where the hypothetical defence counsel is imbued with certain characteristics. This is crucial because what might reasonably be considered credible and relevant to a pugnacious defence counsel (who would spare no effort to put the Prosecution to strict proof and pursue all possible lines of inquiry to try and exonerate an accused), might be starkly different from that to a less pugnacious counsel.

On top of the first, another source of potential challenge is that in a case, Prosecutors may only be able to accurately assess whether an unused material might reasonably be relevant to the Defence’s case or provide a real chance of pursuing a line of inquiry that leads to such material, if they possess the same information and instructions that the defence counsel representing the accused has. But in reality, prosecutors will rarely, if ever, have that at the pre-trial stage. To be sure, where a case falls under the CCDC scheme, as part of the Case for the Defence, the Defence has to inform the Prosecution of its case. Nevertheless, it only has to provide a summary of the defence and the supporting facts, and not every detail underlying the premises and sub-premises of the defence. But an unused material may well be relevant to one of these underlying building blocks to the defence. In addition, aspects of the Defence’s case may shift in the time between the accused’s arrest and the trial’s conclusion.

The Court in Kadar had alluded to this potential obstacle22Kadar, supra n 7 at (115). and others have also pointed this out as a significant reason as to why,23See especially David Plater & Lucy De Vreeze, “Is the ‘Golden Rule’ of Full Prosecution Disclosure a Modern ‘Mission Impossible’?” (2012) 14 Flinders Law Journal 133 at 161-166, Darryl Brown, “Evidence Discovery and Disclosure in Common Law Jurisdictions” in Darryl Brown, Jenia Turner & Bettina Weisser, The Oxford Handbook of Criminal Process (Oxford University Press, 2018) at 549 and “Criminal Discovery in Singapore: A Report prepared by the Criminal Practice Committee of the Law Society of Singapore” (23 June 1998) at 19-20, citing David Corker, Disclosure in Criminal Proceedings, 1st ed (Sweet & Maxwell, 1996). where a disclosure test requires prosecutors to assess relevancy or materiality to the Defence’s case, there will inevitably be cases where the Prosecution assesses its obligations differently from the Defence and the courts. It is true of course that prosecutors, as legally qualified persons, would have had training, for instance, in mooting exercises in their university course, to think of the strongest arguments on both sides of a case. In fact, law students are regularly made to represent both sides of the same case, at different rounds of a moot. The critical difference is that in those exercises, the mooter has access to identical information, regardless of which side they are tasked to represent.

Additionally, the vast majority of prosecutors in Singapore would not have had training or experience in defending accused persons as defence counsels, and hence naturally would not possess the same level of ability to think or strategise outside the box on potential lines of inquiry that might in some way help to exculpate an accused. This is not intended to be a criticism of our prosecutors whatsoever, but a neutral statement of the reality.

Available Solutions and Potential Limitations

The courts did have foresight of these potential challenges. They have offered two solutions to mitigate them:

- where the relevance of an unused material becomes known to the Prosecution only later on at trial, that is when the obligation to disclose arises,24Nabill, supra n 11 at (50). and

- when the Prosecution has any doubt whether it has to disclose an unused material under the law, it should bring it to the court’s attention so that it can rule on it, though the more recent exhortation is that when the Prosecution has any such doubt, it should simply disclose the unused material to the Defence.25Kadar, supra n 7 at (115), Nabill, supra n 11 at (48), and PP v Wee Teong Boo (2020) 2 SLR 533 at (131).

Nonetheless, the extent to which these solutions can mitigate the difficulty prosecution faces may be limited. As regards the first point, the reality is that appearing in court as an advocate during a trial is probably one of the most cognitively taxing tasks that any lawyer may undertake.26Isaiah Zimmerman, “Stress and the Trial Lawyer” (1983) 9(4) Litigation 37. In theory, as each thread of the Defence’s case is revealed during the trial, a prosecutor should be able to identify whether it has any unused material that becomes caught by the Prosecution’s disclosure obligations. In that sense, this neutralises the second source of practical challenge raised above. In practice however, through no fault of his or her own, a prosecutor may not realise that disclosure obligations have arisen vis-à-vis a piece of unused material, given that throughout the trial most, if not all, of his or her mental energy is constantly directed at thinking through what questions need to be posed to witnesses, and how the Prosecution’s case may be proved. This challenge is exacerbated manifold in complex cases where there are numerous issues the Prosecution needs to consider, or where there are quite literally cartons of evidence of which one piece, or a small part thereof, may become subject to disclosure in the middle of the trial.

The second solution, likewise theoretically speaking, is an ideal one in overcoming the two abovementioned sources of challenges – when in doubt, just disclose. The practical reality, again, is that because at the pre-trial stage the Prosecution will rarely have access to the same information and instructions that a defence counsel has in a case, there will be cases where a prosecutor would not even know what he or she does not know about the Defence’s case. Such “unknown unknowns”27A phrase coined by the then-United States Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld. may relate to the breadth of the Defence’s case, in terms of the types of issues, arguments or authorities the Defence may in fact raise, or the depth of the Defence’s case, in terms of how far the Defence may intend to chase down a particular point. Because of the potential existence of such unknown unknowns, if the Prosecution wishes to never fail to correctly comply with its disclosure obligations, would the practical solution not be to disclose (or bring to the Court’s attention) virtually all unused material that it has to the Defence in every case? Yet, the Prosecution would quite understandably struggle with this position because currently as a matter of law, it is clearly not required to go as far as to disclose so much unused material in every case.

The upshot to all of the above is this: At one level, the Prosecution will have to expend substantial manpower and resources to think through all reasonable possibilities, to try to correctly comply with its disclosure obligations in every case. Even then, there will invariably be a not insignificant number of cases where the Prosecution is not able to make the assessment correctly, despite prosecutors having acted with all due conscientiousness and good faith in those cases.28The Prosecution has candidly admitted as such (Nabill, supra n 11 at (44)). See also Lim Hong Liang v PP (2020) SGHC 175 at (14).

Suggestions Moving Forward

To be clear, the practical challenges prosecutors face in complying with its disclosure obligations here are by no means unique to Singapore. Other jurisdictions that impose variants of disclosure tests or obligations on the Prosecution vis-à-vis unused material have also been saddled with practical challenges, and there is a host of literature and studies available, empirically-based or otherwise, examining these issues.29See, for example, Mike Redmayne, “Criminal Justice Act 2003: (1) Disclosure and its Discontents” (2004) Criminal Law Review 441, Hannah Quirk, “The significance of culture in criminal procedure reform: Why the revised disclosure scheme cannot work” (2006) 10 International Journal of Evidence & Proof 42, Joyce Plotnikoff & Richard Woolfson, ‘A fair balance’? Evaluation of the operation of disclosure law (Home Office, 2001), Attorney-General for England & Wales, Review of the efficiency and effectiveness of disclosure in the criminal justice system (Cm 9735) (November 2018), and HM Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate, Disclosure of unused material in the Crown Court: Inspection of the CPS’ handling of the disclosure of unused material in volume Crown Court cases (January 2020).

To conclude this section, several broad suggestions moving forward for our lawmakers to consider are proffered. The overarching proposal is that the Prosecution’s duty should be to disclose all unused evidence it has in its possession relating to the case (for example, in the investigative file), to the Defence at the pre-trial stage, save those (or part(s) thereof) that are protected from disclosure by the law, for instance, because it is privileged or covered by public interest immunity. This duty should be codified.

There are several reasons in support of this recommendation. Firstly, our courts have helpfully tried to ensure the Prosecution is not overburdened in carrying out all its disclosure obligations, by stipulating a number of constraints in when the obligations arise.30Which, as seen above, may be in terms of building in thresholds at which to assess certain evidential dimensions of an unused material, or by limiting the type of unused material to which the obligations apply. But as explained, on hindsight, given the potential difficulties in fully complying with these obligations, the Prosecution is probably ultimately less burdened in terms of time and resources if it were simply required to disclose all unused material, without having to assess anything about the unused material, except whether any is protected by privilege or immunity. Moreover, as the Supreme Court of Canada has pointed out in R v Stinchcombe, fuller disclosure at the end of the day may in fact save time and reduce delays by leading to more guilty pleas and withdrawal of charges.31(1991) 2 SCR 326 at 334.

Secondly, there is likely a considerable difference between requiring prosecutors to assess the value of unused material in relation to the Defence’s case, and merely requiring them to assess whether there is any unused material for a case which should be protected by privilege or immunity. The former, as suggested above, is something which prosecutors are neither fully informed nor equipped to do. The latter, which would involve considerations of informants’ interests and other sensitive matters, is on the other hand something completely within the realm of knowledge and expertise of prosecutors and the police. So not only would prosecutors be in fact able to make the latter assessment in every case, it would in all likelihood overall consume less time and resources if the Prosecution only had to make this assessment, as opposed to both this and the assessment regarding the relevance of unused material to the Defence (or more).

Thirdly, the suggested proposal is but an extension of the Nabill disclosure obligations. The difference is that the proposal does not limit disclosure to only material witnesses’ statements. It also does not require prosecutors to assess the relevance of an unused material to the Defence. It was considered whether the proposal should still require some form of assessment of materiality to the Defence. An alternative could be that prevailing in Canada, which is that prosecutors should disclose all unused material except those which are “clearly irrelevant” (or which are protected by privilege).32Ibid at 339. However, all such tests of relevance or materiality will at least to some extent attract the second source of practical challenge as described above. In this author’s considered view, it is more prudent to leave any such assessment to the Defence.33It might also be wondered whether the Canadian “clearly irrelevant” test imposes such a low threshold that it would in practice mean disclosure of virtually all unused material. If so, the Canadian test and the test proposed here probably have negligible differences. There may be eminently valid concerns that the Defence (particularly unrepresented accused persons) may not have the resources to go through all the unused material disclosed, especially in complex cases where there is a lot of such evidence.34See the insightful arguments made in Brian Fox, “An Argument Against Open-File Discovery in Criminal Cases” (2013) 89(1) Notre Dame Law Review 425, though, in this author’s view, are unlikely to apply in Singapore’s context. However, with respect, the more appropriate solution then is not to impose the onus of the assessment on the Prosecution (which would inflict on it potentially insurmountable challenges), but rather, to increase the resources available to defence counsels as well as the amount of legal aid available (and discussions to achieve this are already ongoing),35Parliamentary Debates Singapore: Official Report, vol 95, “Review of the Case of Parti Liyani v Public Prosecutor (2020) SGHC 187” (4 November 2020) (Mr K Shanmugam, Minister for Home Affairs and Minister for Law). to more adequately equip the Defence to perform the task.

Further, other than the concern of overburdening the Prosecution in assessing its disclosure obligations, there is little reason why disclosure obligations should be restricted to a specific type of unused material. Instead, as emphasised by the court in Nabill: 36Supra n 11 at (44).

“it would be an intolerable outcome if the court were deprived of relevant evidence that might potentially exculpable the accused person simply because the Prosecution made an error in its assessment of the significance of certain evidence”.

This statement surely applies to any kind of evidence, and not just a specific type. Indeed, since the ultimate goal is accuracy in truth finding, as the Court went on to add, the fact that such an error by the Prosecution is made in good faith does not change the analysis. As a matter of principle, this must be correct. And if one accepts the argument raised above that it is overall less burden to the Prosecution if it simply has to disclose all unused material save those protected under the law, then the fairly obvious corollary is that that should be its duty.

Finally, and most importantly, if the Prosecution discloses all its unused material to the Defence, except those protected by privilege or immunity, that would significantly further boost the legitimacy of the outcome of a criminal trial (in particular, convictions), and consequently, of the criminal justice system in Singapore as a whole. No one can go on to question, pursuant to a conviction, that there might be injustice arising from the Defence not having access to evidence in the Prosecution’s possession.

It is worth pointing out that a number of states in the United States also have laws requiring the prosecution to disclose all unused material (that is, no need to assess materiality or relevance).37See especially Darryl Brown, “Discovery in State Criminal Justice” 3 Reforming Criminal Justice 147 at 155 and the footnotes cited, online: <https://ssrn.com/abstract=2951166>. So Singapore would certainly not be alone should the overarching proposal suggested be adopted here.

There have been two main concerns relating to calls for increased Prosecution disclosure of unused material. The first is that it may enable an accused to more easily tailor his evidence at trial. This concern has been persuasively dealt with for instance, by the respective apex courts in Nabill38Supra n 11 at (52). and in Stinchcombe,39Supra n 30 at 335. and needs no further elaboration here.

The second concern is that increased disclosure means an increased risk of an accused person tampering with or endangering the security and safety of witnesses.40Parliamentary Debates Singapore: Official Report, vol 82 at col 2366 (2 March 2007) (Assoc P Ho Peng Kee, Senior Minister of State for Home Affairs) and Parliamentary Debates Singapore: Official Report, vol 87 at cols 413 and 563-564 (18 May 2010) (Mr K Shanmugam, Minister for Home Affairs). This is certainly a powerful concern. The suggestion is thus that in addition to codifying the duty as proposed above, it should also be introduced a new offence specifically for witness or evidence tampering enabled by or witness intimidation arising from access to information through Prosecution’s disclosure of unused material, and harsh presumptive or mandatory minimum penalties should be prescribed for the offence.41Or alternatively, harsh presumptive or mandatory minimum penalties to existing obstruction of justice-related offences, that involve witness or evidence tampering enabled by or witness intimidation arising from access to information through Prosecution’s disclosure of unused material. There is no reason why anyone should be allowed to undermine the potential benefits brought about to our criminal justice system by the introduction of a fuller duty of disclosure. Therefore, the costs of such undermining conduct should be borne entirely by the perpetuator.

Of course, the above merely outlines the proposal in broad terms. There will undoubtedly be numerous operational details that need to be worked out. Some examples include:

- The scope of unused material that should be protected by privilege or public interest immunity.42See, as a starting point, Jeffrey Pinsler, Evidence and the Litigation Process, 7th ed (LexisNexis, 2020) at Ch 5, Part C, Murray Segal, Disclosure and Production in Criminal Cases (Thomson Reuters Canada, 1996, loose-leaf) at Ch 3.3, and Changing Role of the Modern Prosecutor, supra n 2 at Ch 6, Parts 2 and 10.

- What exactly falls under unused material in the Prosecution’s possession (eg. unused material in the police or third-party possession but which was not brought to the Prosecution’s attention).43See, as a starting point, Murray Segal, Disclosure and Production in Criminal Cases (Thomson Reuters Canada, 1996, loose-leaf) at Ch 3, and Changing Role of the Modern Prosecutor, supra n 2 at Ch 6, Part 11.

- How the disclosure scheme interfaces with unrepresented accused persons (there is the CCDC scheme which applies whether an accused is represented by counsel or not, and there is also the Criminal Case Management System scheme which is presently only available to accused persons represented by counsel).44Attorney-General’s Chambers (Singapore), “Criminal Case Management System Request Form”, <https://www.agc.gov.sg/contact_us/criminal-case-management-system-ccms>.

- Should disclosure be carried out by extending to the Defence copies of unused material, or by inviting the Defence to inspect, and make copies where necessary, the unused material for instance at the relevant investigation agency?

Either way, it is suggested that any statutory enhancements to the disclosure scheme as proposed be implemented in incremental stages, as was the case for the CCDC scheme and the recent introduction of video-recorded investigation statements. This is so that there will be sufficient time to assess the workability and efficacy of the scheme, and opportunities to fine-tune its aspects along the way. The ultimate aim should not be to find a scheme that is perfect or has universal acclaim,45Such a disclosure scheme does not exist in the first place. but rather, one that works best for Singapore at the given time.

In writing this part of this article, I have benefited from the research assistance provided by Phone Myat Thu. All errors remain my own.

Endnotes

| ↑1 | See, for example, Justice Steven Chong, “The role and duties of a prosecutor – the lawyer who never ‘loses’ a case, whether conviction or acquittal” (10 November 2011) at (8), <https://www.supremecourt.gov.sg/Data/Editor/Documents/J%20Steven%20Chong%20Speeches/The%20Role%20and%20Duties%20of%20a%20Prosecutor%20(10.11.11).pdf>, Chief Justice Murrell, “Prosecutors as Ministers of Justice – Speech delivered at the inaugural annual ACT DPP Dinner” (2 August 2019), <https://courts.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/1396270/Speech-Prosecutors-as-ministers-for-justice.pdf>, Howard Shapray, “The Prosecutor as a Minister of Justice: a Critical Appraisal” (1969) 15 McGill Law Journal 124. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | One of the most comprehensive study done on the role of prosecutors as Ministers of Justice and the two related aspects of the role in England and Australia is David Plater’s PhD thesis “The Changing Role of the Modern Prosecutor: Has the Notion of the ‘Minister of Justice’ Outlived its Usefulness” (April 2011), <https://eprints.utas.edu.au/10743/2/David_Plater_whole.pdf> (“Changing Role of the Modern Prosecutor”). This author fully commends this magisterial work to interested readers. |

| ↑3 | Cap 68, 2012 Rev Ed, Parts IX and X. |

| ↑4 | Ibid, s 162(1). |

| ↑5 | Ibid, s 165(1). |

| ↑6 | Ibid, s 166(1). |

| ↑7 | (2011) 3 SLR 1205. See also Muhammad bin Kadar v PP (2011) 4 SLR 791, where the Prosecution sought clarification from the court on whether its duty to disclose extended to calling for and scrutinising material pertaining to the case that it had not already been made aware of. |

| ↑8 | Ibid at (113)-(116). |

| ↑9 | Ibid at (113). |

| ↑10 | Ibid at (120). |

| ↑11 | (2020) 1 SLR 984. |

| ↑12 | Ibid at (39). |

| ↑13 | Ibid at (4). |

| ↑14 | Ibid at (50). |

| ↑15 | Ibid at (42). |

| ↑16 | Ibid at (41). |

| ↑17 | Ibid at (54)-(56). |

| ↑18 | See, for example, Kadar, supra n 7 at (86), Nabill, supra n 11 at (41(b)), |

| ↑19 | Chen Siyuan, “The Prosecution’s Duty of Disclosure in Singapore: Muhammad Bin Kadar v Public Prosecutor (2011) 3 SLR 1205” (2011) 11(2) Oxford University Commonwealth Law Journal 207 at 213-214 and Denise Wong, “Discovering the Right to Criminal Disclosure” (2013) 25 SAcLJ 548 at (74). |

| ↑20 | See, for example, Gopu Jaya Raman v PP (2018) 1 SLR 499. |

| ↑21 | Timothy Endicott, Vagueness in Law (Oxford University Press, 2000) at 50. |

| ↑22 | Kadar, supra n 7 at (115). |

| ↑23 | See especially David Plater & Lucy De Vreeze, “Is the ‘Golden Rule’ of Full Prosecution Disclosure a Modern ‘Mission Impossible’?” (2012) 14 Flinders Law Journal 133 at 161-166, Darryl Brown, “Evidence Discovery and Disclosure in Common Law Jurisdictions” in Darryl Brown, Jenia Turner & Bettina Weisser, The Oxford Handbook of Criminal Process (Oxford University Press, 2018) at 549 and “Criminal Discovery in Singapore: A Report prepared by the Criminal Practice Committee of the Law Society of Singapore” (23 June 1998) at 19-20, citing David Corker, Disclosure in Criminal Proceedings, 1st ed (Sweet & Maxwell, 1996). |

| ↑24 | Nabill, supra n 11 at (50). |

| ↑25 | Kadar, supra n 7 at (115), Nabill, supra n 11 at (48), and PP v Wee Teong Boo (2020) 2 SLR 533 at (131). |

| ↑26 | Isaiah Zimmerman, “Stress and the Trial Lawyer” (1983) 9(4) Litigation 37. |

| ↑27 | A phrase coined by the then-United States Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld. |

| ↑28 | The Prosecution has candidly admitted as such (Nabill, supra n 11 at (44)). See also Lim Hong Liang v PP (2020) SGHC 175 at (14). |

| ↑29 | See, for example, Mike Redmayne, “Criminal Justice Act 2003: (1) Disclosure and its Discontents” (2004) Criminal Law Review 441, Hannah Quirk, “The significance of culture in criminal procedure reform: Why the revised disclosure scheme cannot work” (2006) 10 International Journal of Evidence & Proof 42, Joyce Plotnikoff & Richard Woolfson, ‘A fair balance’? Evaluation of the operation of disclosure law (Home Office, 2001), Attorney-General for England & Wales, Review of the efficiency and effectiveness of disclosure in the criminal justice system (Cm 9735) (November 2018), and HM Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate, Disclosure of unused material in the Crown Court: Inspection of the CPS’ handling of the disclosure of unused material in volume Crown Court cases (January 2020). |

| ↑30 | Which, as seen above, may be in terms of building in thresholds at which to assess certain evidential dimensions of an unused material, or by limiting the type of unused material to which the obligations apply. |

| ↑31 | (1991) 2 SCR 326 at 334. |

| ↑32 | Ibid at 339. |

| ↑33 | It might also be wondered whether the Canadian “clearly irrelevant” test imposes such a low threshold that it would in practice mean disclosure of virtually all unused material. If so, the Canadian test and the test proposed here probably have negligible differences. |

| ↑34 | See the insightful arguments made in Brian Fox, “An Argument Against Open-File Discovery in Criminal Cases” (2013) 89(1) Notre Dame Law Review 425, though, in this author’s view, are unlikely to apply in Singapore’s context. |

| ↑35 | Parliamentary Debates Singapore: Official Report, vol 95, “Review of the Case of Parti Liyani v Public Prosecutor (2020) SGHC 187” (4 November 2020) (Mr K Shanmugam, Minister for Home Affairs and Minister for Law). |

| ↑36 | Supra n 11 at (44). |

| ↑37 | See especially Darryl Brown, “Discovery in State Criminal Justice” 3 Reforming Criminal Justice 147 at 155 and the footnotes cited, online: <https://ssrn.com/abstract=2951166>. |

| ↑38 | Supra n 11 at (52). |

| ↑39 | Supra n 30 at 335. |

| ↑40 | Parliamentary Debates Singapore: Official Report, vol 82 at col 2366 (2 March 2007) (Assoc P Ho Peng Kee, Senior Minister of State for Home Affairs) and Parliamentary Debates Singapore: Official Report, vol 87 at cols 413 and 563-564 (18 May 2010) (Mr K Shanmugam, Minister for Home Affairs). |

| ↑41 | Or alternatively, harsh presumptive or mandatory minimum penalties to existing obstruction of justice-related offences, that involve witness or evidence tampering enabled by or witness intimidation arising from access to information through Prosecution’s disclosure of unused material. |

| ↑42 | See, as a starting point, Jeffrey Pinsler, Evidence and the Litigation Process, 7th ed (LexisNexis, 2020) at Ch 5, Part C, Murray Segal, Disclosure and Production in Criminal Cases (Thomson Reuters Canada, 1996, loose-leaf) at Ch 3.3, and Changing Role of the Modern Prosecutor, supra n 2 at Ch 6, Parts 2 and 10. |

| ↑43 | See, as a starting point, Murray Segal, Disclosure and Production in Criminal Cases (Thomson Reuters Canada, 1996, loose-leaf) at Ch 3, and Changing Role of the Modern Prosecutor, supra n 2 at Ch 6, Part 11. |

| ↑44 | Attorney-General’s Chambers (Singapore), “Criminal Case Management System Request Form”, <https://www.agc.gov.sg/contact_us/criminal-case-management-system-ccms>. |

| ↑45 | Such a disclosure scheme does not exist in the first place. |