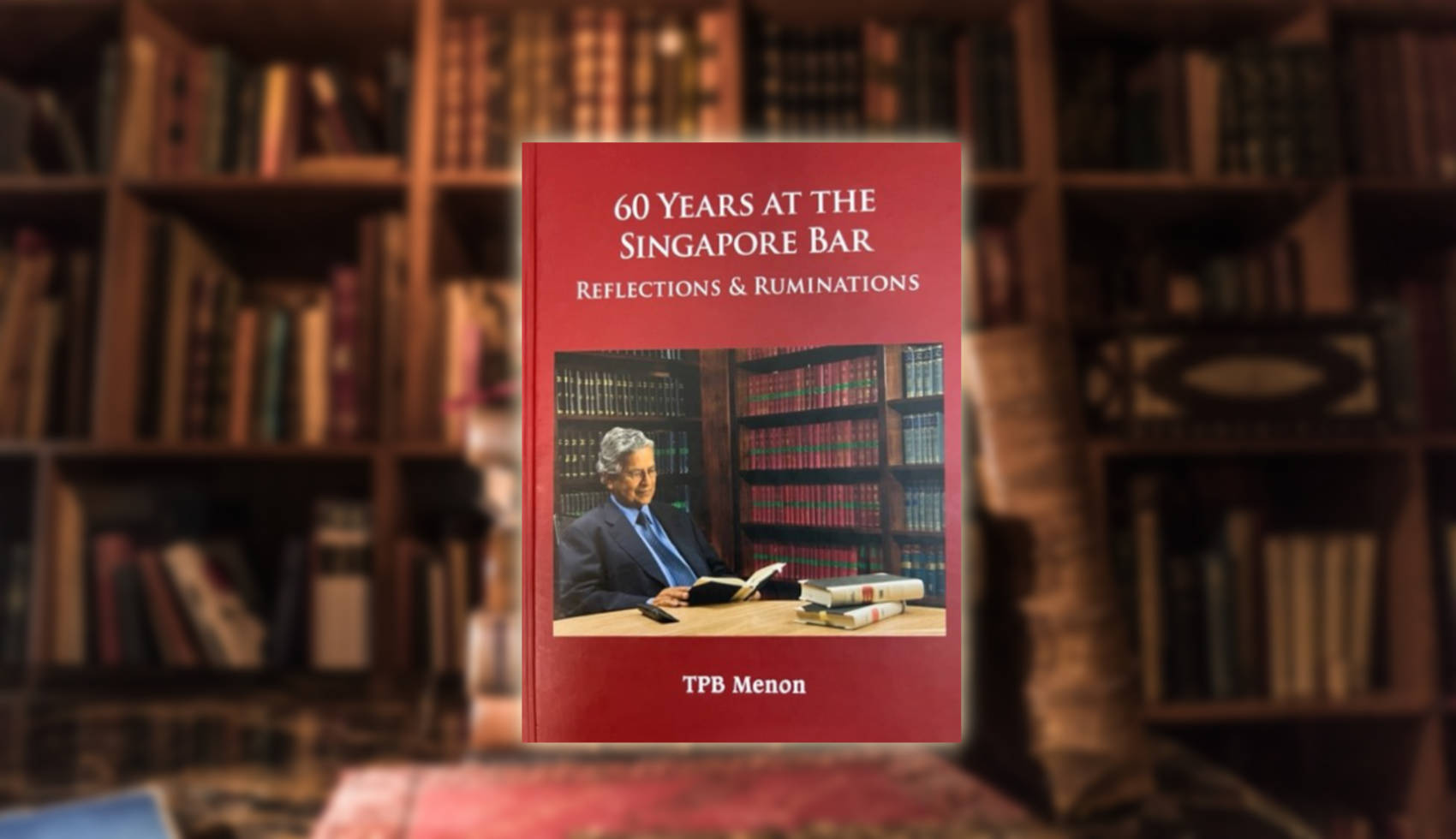

60 Years at the Singapore Bar – Reflections and Ruminations

by TPB Menon (Publisher Talisman)

“When God closes one door, he opens a window elsewhere”, Menon’s mother told him in encouragement after he informed her that the Legal Service Commission had turned down his application for a job after his graduation when all other applicants from his class were successful. As predicted a window did open elsewhere – elsewhere, where sometimes you don’t choose a job, but a job chooses you. Oehlers and Choa, with a chancery practice took Menon in to do his pupillage and soon he was inclining towards specialising diligently in property, trusts and equity law, in time becoming an acknowledged star of the Chancery Bar in Singapore. He has never looked back on his career – not even when former CJ Yong Pung How offered him a judicial post in the High Court, which he politely declined stating that he was comfortably settled in his practice. His refusal, Menon recollects, later cost him the Senior Counsel (SC) appointment as he was reliably told, consequent upon an application made by him. Yong CJ’s successor, Chan CJ in 2011 described Menon as “the most experienced property and trust lawyer in private practice.”

Menon’s recently published monumental autobiography in three parts (456 pages with 46 Chapters), adds his name to that of a few others as Singapore’s contemporary legal historian. It is a bold, compellingly told personal odyssey in the realms of law, its many ramparts and trenches as well as him representing and promoting the legal community’s interests and that of the public as he best thought. It is well documented and sprinkled with lively conversations, letters and anecdotes of the early years of the Law Faculty at the University of Malaya in Singapore (predecessor of the NUS); of having graduated in the Class of ’61 and the evolution of the Bar after independence into the first decade of this century. It is also very much from the perspective of the author having been a Council member of the Law Society for more than 20 years from 1964 and then its President from 1980-83. He helmed the Law Society’s many committees, including the Conveyancing Committee during which time he wrote to the Council of its “retrograde step” being taken (which had the backing of members after an EOGM meeting) in advocating that lawyers be allowed to do the work of Estate Agents, under a Proposal set out in The Solicitors Real Estate Scheme as the conveyancing fee was abolished, resulting in some loss of their fees. In 2005 the AG rejected the Scheme on the grounds of conflict and regulatory hurdles.

Much earlier in January 1985, on relinquishing his Presidency to a veteran, Harry Elias, the incoming President had already written to him, “I cannot quite imagine the Council of the Law Society without TPB Menon; your contributions over the years to the Law Society have been so immense that it is impossible to thank you sufficiently for your untiring effort in the many myriad activities of the Law Society.” But Menon’s contributions were not without personal disappointments which Harry Elias also noted in his letter.

However, as one service to the Law Society ended another onerous one replaced it. In 1991, notwithstanding that he had earlier declined to accept a judicial posting, Menon was nonetheless alongside his legal practice, appointed Chairman of the Law Society’s Disciplinary Tribunal by Yong CJ, an office he continued to hold for some 14 years, becoming its longest holder.

Menon had also headed the Strata Titles Board as President; was a member of the Market Surveillance and Compliance Panel (Energy Market); was on the Military Appeal Court’s panel of Judges; Deputy Chairman of the Board of Legal Education; and one time President of the ASEAN Law Association (ALA).

His varied experiences had enriched him with relevant insights into the workings of legal institutions and the law, allowing him to take an independent and spirited initiative and stand on many controversial issues of the day as narrated by him, supported with relevant documents, which authenticate and reveal his dedicated interest in promoting objectively, just and ethical laws and practitioners’ behaviour, never intent to see the bar lowered. Fittingly he was bestowed with a Public Service Medal in 1993 and later in 2004 with a CC Tan Award by the Law Society which latter award exemplifies the ideals of honesty, fair play and integrity.

The book begins with Parts A and B, in which he pays tribute to his traditional family and narrates his submission to a medieval ordeal by fire requested by his father over a minor accusation by a friend, to establish his honesty by which he has all along lived. He then goes on to chronicle briefly, his personal journey in law from his student days, the historical first intake of law students in 1957 into the Law Faculty, including three colleagues (Tommy Koh, currently Ambassador-at-large and a prodigious author, Thio Su Mien who both in their early years were Deans of the Faculty of Law, and a third colleague Chan Sek Keong who took office as the AG and later as Chief Justice (2006-2012)).

He further alludes to his interaction with the Law Faculty’s teachers and other students and being a part-time tutor in conveyancing. He developed a friendship with Professor Sheridan, in his mid-nineties now and living in the UK, whom he has occasionally visited. Sheridan, a scholar and educator, was recommended by Sir Ronald Braddell, a lawyer, historian and Colonial Adviser. Sheridan joined the Faculty at a very young age as its first Dean in 1957, shaping criteria for admissions, courses, legal curriculum and policy developments at the Faculty aligning it with local culture and needs, working with his efficient Chief Executive, Chua Boon Lan. However, his sudden resignation from the Faculty in October 1962 took the faculty by complete surprise as it came just after a three-year extension of tenure. Menon tells of Sheridan being consulted for a legal opinion by Ong Eng Guan (one time Mayor of Singapore and later a Minister in the Government nurturing a higher ambition). As a result, Sheridan had unexpectedly incurred the displeasure of then Prime Minister Lee, with the Deanship going to Professor Harry Groves, an American with a military background who was appointed under an Asia Foundation Grant the following year. Menon tells of Groves edifying himself with reports to the Asia Foundation in Kuala Lumpur and further misreporting with his “coloured reports” of the University as becoming unfavourable for foreigners and left the Faculty.

In particular Menon recollects his early personal ties with Justice Mohamed Suffian who became Malaysia’s 4th Lord President of the Federal Court from 1974-82. He served with him on the Board of Examiners of the Law Faculty and then the Council of the Asean Law Association (ALA), of which, each separately was President. Menon enjoyed Suffian’s broad knowledge of the law and his human side narrating anecdotes, one of which was that when asked at a Convention by delegates where he had disappeared to at the break for lunch his answer simply was that he had gone down to give his driver a lunch packet.

As for Menon not getting a job with the legal service after graduation, Menon learned soon afterwards from Mr Mallal publisher of the MLJ, and a friend of the then AG, that the reason was he had whilst a student written an article for The Fajar, a University Socialist Club publication which was regarded as left wing. Menon reproduces a photo image of the April 1960 article, “Is our University Colonial?” in which he believes he merely exposited harmlessly the ambiguity of the word “colonial”. The question had been posited by Mr Lee (who had a year earlier become Prime Minister) and in reference to his take on the word, in an otherwise wide ranging talk at Nanyang University on ”Language and Politics”.

Recalling the completion of his pupillage and additionally his Post Final Practical Law Course (PLC) Menon was ready to be admitted to the Bar, but faced another hiccup. It seemed his PLC training had come to nought. The legislation recognising his PLC course had been delayed. Fortunately, no objections arose to his call. The Chief Justice Sir Alan Rose (a man of jovial disposition whom Prime Minister Lee had brought in from Sri Lanka in 1958) welcomed him to the Bar.

Eric Choa gave Menon a job immediately in the firm. Soon afterwards, recognising the quick grasp of chancery practice including some hard lessons Menon had also learned from Wee Eng Lock, a “perfectionist conveyancer”, a fact which Mr Wee had made plain to Menon, Eric Choa decided to give Menon a somewhat difficult brief to handle in the High Court – this time to be an ordeal by battle. Disappointment came early when he lost the battle. Being a survivor and believing in his client’s cause Menon appealed. He consulted Punch Coomaraswamy a senior practitioner and subsequently an Ambassador, a Judge and Honorary Member of the Law Society, who recommended CC Tan, a respected senior lawyer from Tan Rajah and Cheah, and also one time politician and legislator. CC Tan won the appeal. Thereafter, CC Tan gently advised Menon over a cup of coffee in his office, that doing conveyancing work was not enough. He also had to have one foot firmly in the Court to be recognised by the Judges as a chancery lawyer. Menon went on determinedly to do exactly that, fulfilling the advice given and in fact doing much more by starting to actively participate in the profession’s work and of other tribunals and committees.

Menon’s engagement with the Bar Committee and later its successor, the Law Society, was also initiated by Punch Coomaraswamy. After losing his first election to R Ramason, a genial practitioner he succeeded the following year in 1964, and for more than 20 years after that. He was elected President of the Law Society in the years 1980-1983.

On being elected President, as was the custom, he went with his Deputy to pay a courtesy call on Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin, who was the first Asian lawyer to hold that office in 1963. Menon also wanted to raise with him the government’s intention to allow a foreign law office Freshfields from UK, to practice in Singapore, which he and the Council of the law Society did not support. On his election as President, the Chief Justice told him “Mr Menon, it is good to be popular, but the question is whether you can do the job”. On the issue of Freshfields’ intended admission here the Chief Justice said that the issue was for the Law Society to decide. As for himself he emphatically stated, “My job is to make sure that they (pointing to City Hall, next door which was then the seat of Executive power) do not sit here”. Wee CJ the longest serving CJ was honoured by the University of Oxford with an Honorary doctorate degree in law and retired in 1990 after 27 years of service.

Whether CJ Wee knew it or not, Menon’s intention as it appears from his autobiography was not to be popular but “to do the job” Wee CJ had spoken of and which he had already started to do courageously and meaningfully as his conscience dictated, serving the larger interest of the members of Law Society and the community.

The earnest engagement had in fact begun in 1967 when Toh Chin Chye, (the tough talking) Deputy Prime Minister, summoned the Bar Committee’s Council members (as it was then known) and castigated its members for not taking on the training of lawyers, which the Law Faculty had been doing with its own allocated funds and that the University would cease doing so.

Menon immediately began collaboration with Punch Coomaraswamy, who took the initiative to draft The Legal Profession Act of 1967 that helped to make an overall reform in the governance of the Law Society. First, structurally in respect of electing member representatives to the Society’s Council. This was done by creating three categories of lawyers, the Senior, Middle and Junior categories. Each category, with specified numbers, would elect its own members to the Council who wished to be on the Council, so that the legal profession was represented at different levels in the Council, a practice that continues. Second, the Board of Legal Education was established to conduct Post Graduate Practical Law Courses with Menon making sure that Ethics was taught as a subject, over the voices of some that it was unnecessary and quite rightly so for the law without ethics can be likened to a body without a soul. Third, the appointment of an Administrative Executive. Fourth, the inducting of tutors who were expert in their subjects from various disciplines of the profession and fifth, the conduct of admissions and for the making of other governing rules. Much later consequent upon a report submitted in 2001 by a Review and Redesign Committee of foreign experts, the Practical Law Course was modernised and continues to be, to meet evolving standards of teaching and legal practice.

Going back to the early years, in 1972, Menon, successfully led the Law Society to object to a proposal by the government to a lay member being made part of the Disciplinary Committee, putting up a paper to the government, stating that an outsider would add no value to the process and that it would breach the privilege of the lawyer to be judged by his own peers. He dispelled the government’s argument that the Bar should not sit on judgment of its own members by answering that any untoward finding would be corrected in the Supreme Court which had overall control of lawyers.

In 1973, he voiced his stand to the President of the Law Society Mr Karthigesu (later Karthigesu J) that the Council was succumbing to being dictated by many quarters, including civil servants, and the Council was becoming weakened and to table the letter for the Council’s discussion, but to no avail.

Perhaps one of the saddest and most heart-rending moments that he experienced was in 1973 – a matter in which the law as interpreted had numbed common sense and justice. An applicant for admission to the Bar had completed the last 10 days of his training as a pupil at home, with continued supervision by his Master from the office with assignments as he was recovering from injuries from an accident and not in the physical presence of his Master in his office as the Rules stipulated. The Master had vouched for the same and with an Opinion from Menon that for all practical purposes there was substantial compliance with the Rules. He also drew a parallel, that legal service officers elsewhere but not directly under the AG in his Chambers were nevertheless being admitted. The Application was nonetheless denied by the Court on the AG objecting. Later, on fulfilling the letter of the law the Applicant was admitted but was unable to secure a job. He ended his life.

In the mid-seventies on the issue of’ caning Menon was revulsed enough after reading a Straits Times article “Branding Bad Hats for Life” by PM Raman which quoted a blow by blow account of caning meted out to prisoners by the Director of Prisons, Quek Shi Lei, scarring them permanently for life, to write strongly, to the Council, as a Council member, to make representations to the authorities to end such inflicted miseries as well as advocating abolishing the mandatory death sentence, and later reasoning the inhumane and archaic nature of the death penalty.

There were other episodes of concern on which he had taken a strong stand.

In 1976, he was instrumental in blocking the application by a past President Graham Starforth Hill one of the leading lights of the Bar, from wanting to continue his law practice in Singapore whilst living in the UK in infringement of the Rules.

In about 1980, Menon led his Council in opposing the government’s announcement of declaring an Open Door Policy in admitting Freshfields, a foreign firm from the UK to practice in Singapore contending amongst other things, that there was no lack of foreign expertise amongst its lawyers, and engaging with the AG, the government and the press to reject the move. Freshfields was nevertheless admitted to practice locally in August 1980 under conditions not known to the Law Society, save that they should not engage in conveyancing work. The conditions not surprisingly were breached, resulting in their license to practice being cancelled in 1988.

In September 1980, soon after Menon was elected President of the Law Society, the AG Tan Boon Teik summoned him to his Chambers requesting his support and to influence his Council to support the admission of Hong Kong (HK) lawyers to the local Bar as the British were returning the Colony to China. Menon told him they had gone through this sort of discussion before in the Freshfields affair. In a tension filled conversation both lost their cool, with Menon leaving his office but then returning. He was piqued by the AG describing him as “a mere factotum of the Council”. Menon believed that he being the elected head of the Law Society, the AG should not be labelling him as such and dictating to him as to his role and that of the Council’s freedom to make its own decision. His view was that the previously held assumption in the UK that the AG was the head of the Bar no longer applied here under the Legal Profession Act. To his recall, not long afterwards an invited delegation of HK lawyers to the Istana for a function behaved like upper class “Brahmins”. Subsequently lawyers from HK were allowed to practice here in partnership or associateship with a local firm. The upshot – only one lawyer applied and was registered.

But law and lawyers follow where business goes. In contrast, in less than a generation after the faltered UK and Hong Kong experiences, an inflexion point set in, in the last decade, changing the legal and judicial landscape in Singapore in response to the unstoppable tide of globalisation with the need for simultaneous multi-jurisdictional transactions in international, commercial, banking and regulatory services to be processed as well as the need for a disputes resolution machinery in these areas to be addressed. Timely initiatives taken from 2013, by the Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon resulted in establishing the Singapore International Commercial Court (SICC) presided by a local Judge in which foreign Judges and others with necessary expertise on a subject may sit. Alongside, the Singapore International Mediation Centre (SIMC) was set up and foreign registered lawyers and their overseas firms admitted or allowed to amalgam with local ones, under compliance rules and to appear and practice in the SICC and SIMC. Both the new institutions and the earlier existing Singapore International Arbitration Centre have made Singapore a coveted and busy dispute resolution hub in Asia.

The final Part C of the book constitutes his “Comments on Cases” – a critique of some 20 or so cases, some with arresting titles (like God’s House Divided, (2011), David and Goliath (2004), The Law Made to Stand on its Head (1997),) on the Administration of Estates, Property and Trust law stretching back to his early days of practice. He believes that the law exposited in some of them including a recent one, Lee Suet Fern require judicial reconsideration. Then there have been the handful of recently decided landmark cases in the Court of Appeal on Constitutional issues which have stirred much public interest. Menon analyses the infamous section 377A case which criminalises sex between men under the Penal Code (2015) recently revisited and reaffirmed in 2022 (but now awaiting repeal under a Bill introduced in Parliament on 20 October 2022) and those described as The Elected Presidency (2017), and The Voice of the People (2019) shorn of much legalese for easier understanding and gives his take on them as to their correctness for the reader to discern.

The autobiography, in a read as you would talk Lord Diplock style, handsomely bound, and borne out of a lifetime of the author’s knowledge of law and experience makes for a rich and immersive reading for the legal profession and those interested in the law.