Furthering Access to Justice, the PDO Way

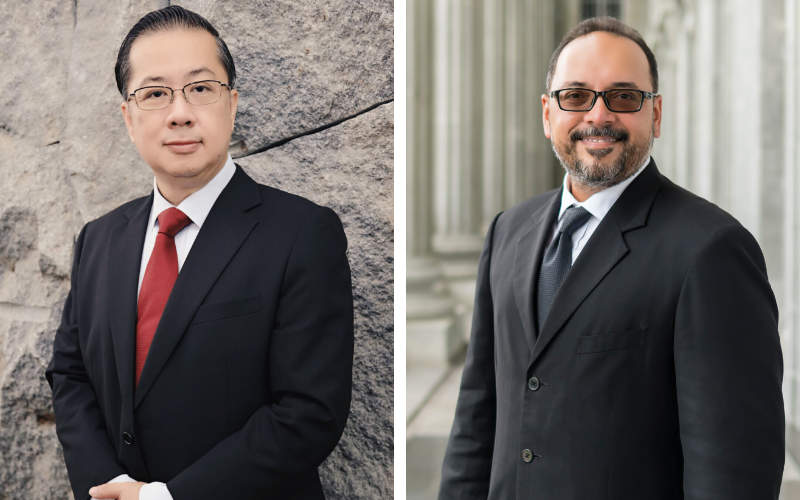

The Public Defender’s Office was launched in December 2022 to provide criminal defence aid for eligible accused persons facing non-capital charges and cannot afford legal representation. Eight months on, we speak with the Chief Public Defender, Mr Wong Kok Weng (WKW), and the Deputy Chief Public Defender, Mr Anand Nalachandran (AN), to find out how the journey has been thus far.

(Left to right) Wong Kok Weng, Anand Nalachandran

Good morning guys. Congratulations to both of you on your appointments. You have both come from very different paths before your present appointment. Can I find out how the transition for both of you has been?

WKW: I joined the Singapore Legal Service in January 1988 after graduating from the National University of Singapore. I was appointed a Deputy Public Prosecutor (DPP) in February 2000 and remained in the Attorney-General Chambers (AGC), Crime Division until I accepted the transfer to the Ministry of Law (MinLaw) in April 2022 to help set up the Public Defender’s Office (PDO).

I was the only one transferred over from Legal Service. The rest of our public defenders (PDs) were hired directly by MinLaw. At present, we have a total of 14 PDs (including Anand and myself).

Having been a prosecutor for over 20 years, this new role advocating for the defence was a big change for me. However, I saw the setting up of the PDO to help the needy as a good thing as it enhances access to justice. This mindset inspired me to make the change and to overcome the challenges of the transition.

AN: I practised as Defence Counsel for over 20 years before joining the public service earlier this year so I expected adjustments – but while some things are different, many things remain the same. Essentially, I believe in the objectives of the PDO – and to put it simply, it felt like the right thing to do and the right time to do it.

Can you tell us more about the PDO?

WKW: The PDO was established to provide legal advice and representation to eligible accused persons charged for committing non-capital offences but cannot afford a lawyer. Previously, such accused persons could only seek pro bono legal aid under the Criminal Legal Aid Scheme (CLAS) administered by Pro Bono SG (PBSG).

As PDs, we provide a voice to those who are unable to seek legal representation on their own and strive to seek the best legal outcome for them. This can be done through mitigating with the prosecutor to dispose of the case through diversionary measures or lowering the severity of the charges, or with the judge for a lower sentence. If that happens, the person on aid would have benefitted from our work. If it does not happen despite our best efforts, it does not mean that the PDO has failed. Of course, where there is a reasonable defence, we will defend the case rigorously at trial.

AN: The barometer of performance or success in criminal defence aid is not merely the outcome of the case. The PDO strives towards stringent processes for means and merits testing, as well as robust lawyering for eligible applicants granted criminal defence aid.

How does the PDO work alongside CLAS?

WKW: When we first formed the team to develop the various workflows and arrangements, we had to learn a lot from PBSG because they had been running CLAS for a long time. We held many meetings with them and considered some of their best practices and incorporated them into our processes. To date, our operations team continues to engage them regularly to make sure things run smoothly.

With the establishment of the PDO, Singaporeans and permanent residents who require legal representation may apply for criminal defence aid. The PDO will assess the means and merits of the applicants to determine their eligibility for aid. PBSG also assists us with merits testing for some applications. After an applicant is assessed to be eligible for aid, his/her application will be allocated either to the PDO or PBSG. More information on the application process can be found on the PDO’s website (https://pdo.mlaw.gov.sg). The main difference now is that the Chief Public Defender decides on whether an applicant has passed the means and merits tests and is eligible for Government funded aid, something which was previously under PBSG.

AN: CLAS has been around for decades and in certain aspects, PDO is not going to re-invent the wheel – but of course, there will be some differences in processes and systems.

How do you decide what cases are allocated to CLAS?

WKW: We will first consider the urgency of the case. One example would be certain remand cases whereby the remand period may outstrip the eventual sentence of the applicant. Another example would be minors reaching 21 years of age. Such cases are assigned to the PDO to ensure that legal representation is provided as early as possible. For non-urgent cases, we don’t discriminate between the PDO and CLAS. What I mean is that cases assigned to CLAS are not based on any distinction as to its nature or complexity.

AN: The main levels of filtering include eligibility – means and merits – and urgency. Thereafter, the allocation of cases is not based on what is perceived to be a better or worse case.

Is there a difference for the means/merits test between how CLAS had used to do it as compared to how you guys are doing it?

WKW: The means test criteria have changed. Previously, applications to CLAS are assessed based on the applicant’s disposable income and assets. Now, we consider an applicant’s monthly per capita household income (PCHI) and bank savings and investments to determine his/her financial circumstances. The PCHI threshold has been raised from $950 to $1,500 to increase coverage.

We have also established a PD Board comprising lawyers from private practice and myself, to allow for greater deliberation on the legal merits of applications involving offences that are punishable with imprisonment of more than seven years.

There is also a means test panel appointed by the Minister for Law that comprises private practitioners and community leaders, and they can review cases that do not, on first blush, pass the means test. These are often cases with a lot of extenuating circumstances such as a family member who is very sick and there are lot of bills to pay. So even though the income is above the PCHI, the means test panel can decide that a particular applicant has satisfied the means test.

AN: The threshold of the means test has shifted. So that is one big change. In terms of merits assessment, we now cover more offences. So our scope has really expanded in both aspects.

And are you still looking to hire?

WKW: We have started our operations with a modest pool of PDs and intend to scale up over the next few years. So yes, we are constantly looking out for new talents to join our team.

What are you looking for?

AN: Within the PDO, there are officers of varying levels of seniority and experience. We look for something different from a junior and from a senior. For a junior, we want someone with commitment for this type of work. For the middle tier, we need someone with experience and the ability to lead and manage juniors. Ultimately, I guess the idea is to find the candidate that fits the role that the PDO needs at that particular point in time.

WKW: Yes, I should add that a big part of our hiring is through the interview process. Of course, you can never be sure through one interview that this is the perfect fellow. So we look through their resumes, identify candidates with good qualifications, and preferably those who are involved in community engagements like pro bono work or volunteer activities.

AN: The fact that a candidate was already doing pro bono work in practice helps. Obviously, it is not determinative but it shows that the commitment is there. These lawyers have taken the available opportunities and now maybe want to elevate that to another level.

WKW: During the interview, we will talk to them and ask why they want to leave. In fact, many of the candidates that we see are doing well (from big firms), so we want to know why they want to switch to the public sector. We will ask questions to determine that they are coming in for the right reasons. We tell them upfront that we are not going to pay them what they are getting outside and they will have no shortage of clients as we get applicants every day. So they will have to deal with a workload that requires them to go to court every other day. We need to spell it out upfront and let them know what to expect. So if they are just thinking of money, then the PDO is really not the place. They must be motivated by something higher.

AN: We take candidates from mixed levels and backgrounds. Local universities and foreign universities. Big firms and small firms. Some with criminal practice backgrounds and some without. We look at what their motivations are, as the idea is always to try to find the right person with the right fit, to find somebody who believes in what we are trying to do.

Would you take someone without any background in disputes?

WKW: Yes. In fact, some of our junior officers only have prior experience in corporate work. I will always ask for their reasons for wanting to join the PDO. Some have shared that they want to be able to do more criminal law work but do not have many opportunities to do so in private practice, or that corporate work did not suit them.

AN: Opportunities in criminal practice, especially for young lawyers, may not be common. The PDO only came into existence last December so those who graduate now will have this opportunity, but those who graduated prior to that did not have this option.

WKW: I will add that you will need to know what your calling in life is. The kind of work we do at the PDO is to serve the public, so if you want to join us, you must have the proper mindset and commitment to bring your talent and skills here to do this kind of service.

Of course, private practice lawyers do serve, but they are ultimately constrained by the need for revenue and to keep the practice going. We are not so constrained, and you can focus on purely helping those on aid.

AN: Some lawyers do a lot of pro bono work and that is a personal choice and commitment. We are ultimately looking for people who are aligned with the PDO’s objectives.

What sort of career path does the PDO offer to young lawyers?

WKW: Well firstly, within the public service career structure, there are well-defined progression paths that allow officers to rise through the ranks if they have performed well and demonstrated the relevant competencies at the next higher level. Secondly, there are opportunities for lateral movements within MinLaw if they wish to be exposed to something different, say legal policy work. On top of that, we are looking at building up the capabilities of our officers through proper training milestones and programmes.

What distinguishes the PDO?

AN: I find that we are able to do things which I found difficult in practice because we are part of the larger public service. For example, applicants come with a legal problem but many also have other problems such as psychiatric, financial, social or family issues, and in practice there is a limit to how much you can help outside of the legal issues.

Here, there is the opportunity for us to identify the non-legal issues underlying the legal problems and we can help with referrals and connections for social support and assistance. So while we focus on the legal issues, we can provide referrals for longer-term solutions so that hopefully, we do not see applicants coming back. We don’t want repeat customers.

WKW: Indeed, we can refer cases to the social service agencies so this is not all that unique. For example, we recently had a case where an aided accused person faced charges arising from a dispute with his neighbour. He is wheelchair-bound and lives on his own. Due to the criminal proceedings, he discharged himself from hospital against medical advice. On assessing the circumstances, including the mobility issues, the assigned PD conducted the interviews at his home and convinced him to be re-admitted to the hospital for his medical conditions. Further, the PD wrote representations and the Prosecution agreed to issue a warning and withdrew the charges. This kind of story is not uncommon. The life circumstances of a legally aided accused person may throw up many problems, and we are in a unique position to be able to help in some way.

AN: I found this to be very compelling because we have the opportunity to provide a more holistic solution to a problem. And again, hopefully this is a better and longer-term solution.

WKW: Over the last eight months or so, I have seen this batch of PDs standing high. I think that we have picked the right people with the heart and empathy, and who are doing good work. I hope that as the PDO evolves over the years, this passion and desire to help vulnerable individuals will continue growing.

What do you miss from your previous roles?

WKW: I think what I missed about being a DPP is the people that I have worked with in AGC. I have worked there for the last 20 over years and I think it is an organisation that does a lot of good work. Over the years I have also seen AGC constantly evolving and always trying to do better and to do what is right. The emphasis is not to get a conviction by all means, but a legal outcome that is just and fair. A strong culture has grown around this notion of justness and fairness which is what keep the DPPs going. I enjoyed working in that culture as it resonates with my personal values. I also miss working with my former colleagues who have always shown me kindness and helpfulness.

Over the years, I also had very good mentors in Crime Division such as Lawrence Ang, Ong Hian Sun, Jennifer Marie and Bala Reddy who have taught me not only professional skills such as court craft but also personal values of humility, integrity and excellence.

AN: I did not expect to miss going to court and the Bar room this much. In a way, what we do here is not all that different from what Defence Counsel would do in private practice. We are still providing criminal defence, except that we deal with a specific demographic. So the work itself is not that different from what I used to do. I guess one difference is that my current role is more supervisory and involves less interaction with clients and less interface with the Court. I used to go to court regularly so I look forward to opportunities to go to court again – and there will be cases that we feel are appropriate for either one of us to attend.

Can you share your favourite part of your job and what some of the challenges you face?

WKW: Inspiring the young PDs to do their best when representing those on aid despite the workload and challenges. Whenever there is a beneficial outcome and I see the smile on their faces, I feel heartened. You can see the passion in these young PDs and I would like to keep that fire burning in them. Therein lies the challenge, in keeping that passion and spirit going. How can I inspire them as a leader? This is something I have to deal with and seek improvement on. On a macro level, the challenge is ensuring the work processes are efficient so as not to hold up court processes. We want to ensure that applications are processed quickly and PDs assigned expeditiously, so that each case can move along without unnecessary delay.

AN: I value the opportunity to make a positive impact – and perhaps therein lies the challenge. It is not that I did not feel that I was making a positive impact in practice, but this was an opportunity to help establish the PDO and make an impact on a larger platform. I wish I could tell you that there was a more insightful point of inflexion or introspection that prompted the move, but it was really just thinking that the PDO was a really good development and wanting to play a part. I thought this was a good opportunity to do something good.