Addressing Client Dissatisfaction – A Primer for Law Practices

Addressing the concerns of a dissatisfied client is a common and inevitable occurrence in legal practice. Client dissatisfaction may be due to a wide range of reasons. A recent report released by the UK Solicitors Regulation Authority revealed that the most common complaints to UK law firms concerned delay, failure to advise and excessive costs.1Solicitors Regulation Authority, Risk Outlook 2020/21 (23 November 2020) < https://www.sra.org.uk/sra/how-we-work/reports/first-tier-complaints-2019/> (accessed 18 March 2021). Although not all client complaints can be successfully resolved through an in-house client complaints procedure, the report noted that between 2012 and 2019, UK law firms resolved a higher proportion of complaints in-house, with the rate of resolution of complaints increasing from 72 per cent in 2012 to 80 per cent in 2019.2Ibid.

This article outlines how Singapore law practices can better address client dissatisfaction through both an internal and client-facing complaints procedure.

Where to Start – Internal Complaints Handling Procedure

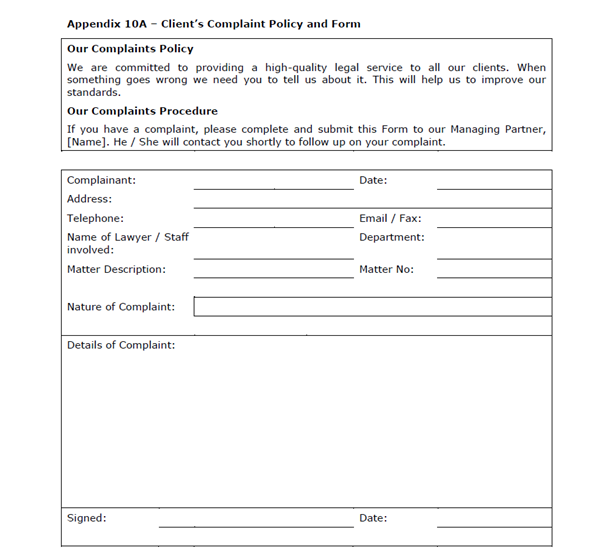

In 2017, the Law Society of Singapore published an updated version of its Practice Management Guide (the Guide),3<https://www.lawsociety.org.sg/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Practice-Management-Guide-2017.pdf> (accessed 18 March 2021). which provided, as part of a sample office guide, a sample internal policy for handling client complaints.4See Section 10.7 and Appendix 10A at pp. 116-118 of the Guide. The preamble to the sample policy noted that how law practices responded to client’s complaints was “an important indicator of [their] professionalism”. Following the old adage “[p]revention is better than cure”, the sample policy provided some pointers on how to prevent complaints in the first place:

“At the outset, we expect the lawyer to anticipate a complaint arising from the difficulties that the client has encountered in his or her dealings with the lawyer. At this stage, it may be possible to resolve the problem or misunderstanding. A nicely worded verbal or written apology and assurances that the difficulties will be addressed may persuade the client not to make the complaint “official”. Do not become defensive or emotional and do not try to avoid the client as this will make matters worse.

It is recommended that you bring your Supervising Partner into the picture as soon as you encounter any difficulties with your client in order to prevent these difficulties from accelerating into a complaint against you. This is also likely to assure your client that his problem is receiving attention from someone with higher authority than you in the Practice.”

The sample policy then outlined the next stage of the internal procedure if the lawyer was unable to resolve the client’s complaint informally:

“If you are unable to satisfy the client at this initial informal stage, you must:

a. Report the complaint to your Supervising Partner; and

b. Provide the Client with the Client Complaints Policy and Form (Appendix 10A).The Head of Department / Risk Management Partner is responsible for ensuring that all complaints received from the clients are duly investigated and dealt with. A copy of the Complaints form will be send to the Risk Management Partner who must be kept updated on the actions taken and status of the Complaint.”

The sample Client Complaints Policy and Form in the Guide (reproduced below) reassures the client of the law practice’s standards of service and that the law practice will follow up on the client’s complaint after the relevant details have been provided.

Moving to the Next Level – Good Practices

The sample policy in the Guide provides a good starting point for establishing an internal complaints handling policy. There are a number of good practices that law practices can adopt in refining their internal policy.5In identifying these good practices, the author had also reviewed a number of sources, including the complaints handling procedures published on the websites of a number of UK law firms. Other sources are identified in the subsequent endnotes. Three examples of such good practices are set out below.

1. Inform the client of the estimated timeline for processing the complaint

The law practice’s internal policy should state that it is good practice to inform the client of a specific timeline for the law practice to process the complaint. Such a practice will reassure the client that the complaint will be attended to promptly. The estimated timeline for processing the complaint should include the time taken to provide a written acknowledgement of the complaint. Assuming that the complaint is not complex and the law practice’s resources permit, a reasonable working timeline to provide a substantive response to the client may be around two to three weeks. The sample Client Complaints Policy and Form in the Guide can be adapted to include a suitable timeline.

2. Identify the right person to handle the complaint6Tracey Calvert, Anthony E Davis and Richard Harrison, “Review processes and client satisfaction: handling high-risk cases” in Hermann J Knott (ed.), Risk Management in Law Firms (Globe Business Publishing, 2014), para 5.2 at p 140.

It may not always be appropriate for the same person in the law practice to be designated to handle all client complaints. Much will depend on whether the complaint should be handled formally or informally. For example, the Law Society of England and Wales has given guidance that a complaint about a failure to return a phone call may be resolved by the recipient promptly calling back and apologising, whereas a formal written complaint to the partner responsible for handling complaints should be responded to by that partner.7Law Society of England and Wales, “Handling complaints” (Practice Note) (19 February 2021) at Section 6.1 <https://www.lawsociety.org.uk/en/topics/client-care/handling-complaints> (accessed 18 March 2021).

Law practices should consider providing in their internal policy as to when a lawyer having conduct of the client’s matter should resolve the complaint on his or her own where appropriate, and when the complaint should be handled by another lawyer or escalated to senior management.8Supra, n 6 and n 7.

On a related note, the importance of an independent person within the firm to investigate the complaint has been highlighted in the UK, although this is recognised as not always being appropriate or possible.9Supra, n 6 and n 7 (at Section 6.4). For UK sole practitioners, it has been suggested that an independent person outside the firm could be involved in investigating the complaint.10Rebecca Atkinson, Assessing and Addressing Risk and Compliance in Your Law Firm (The Law Society, 2020), para 1.1.3 at p 4.

3. Identify when “client dissatisfaction” can arise

Lawyers should not assume that clients are dissatisfied only when they submit a formal written complaint to the law practice. As noted by the Law Society of England and Wales, clients may express dissatisfaction informally and lawyers should “pick up on these cues and deal with the issue promptly, to avoid escalation of the matter”.11Supra, n 7 at Section 2.

As a reference point, the Law Society of England and Wales has defined a “complaint” broadly as “any expression of dissatisfaction, whether oral or written, which alleges that the complainant has suffered financial loss, distress, inconvenience or other detriment”.12Ibid. Some UK law practices have formulated a more neutral definition of a “complaint” by, for example, referring to concerns about the quality of work or level of service provided rather than what the client had suffered.

At the same time, not every expression of client dissatisfaction should trigger the internal complaints handling procedure.13Supra, n 10, para 1.1.2 at p 4. As mentioned above, lawyers and law practices should be proactive in preventing complaints in the first place. They should also take a common sense and practical approach to sieve out minor instances of client dissatisfaction through, for example, the lawyer having conduct of the matter attending to the client’s concerns promptly.14Ibid.

To guide its lawyers and staff, the law practice’s internal policy should therefore explain what client dissatisfaction is and when it would usually trigger the internal complaints handling procedure.

Client-facing Complaints Procedure

From a client-facing perspective, the sample Client Complaints Policy and Form in the Guide offers a good platform for law practices to consider other useful information that should be given to a dissatisfied client. Besides indicating the estimated timeline for processing the complaint as mentioned above, another point may be to assure the client that he or she will not be charged by the law practice for handling the complaint.15Supra, n 7 at Section 6.3.

It may also be useful to explain to the client whether, and to what extent, the complaints handling process would have an impact on the client’s matter.16Ibid.

In addition, the law practice may wish to invite the client to indicate his or her desired outcome from the complaint. This may help to focus parties’ efforts on resolving the complaint, instead of adopting a confrontational approach, especially where the issue is only about the quality or level of service. In this regard, the law practice may also wish to propose a meeting with the client to discuss, and try to resolve, the complaint. If this approach is taken, the law practice should also provide to the client information such as: (a) the estimated timeline of when such a meeting will usually be arranged; and (b) the steps to be taken by the law practice following the meeting.

The above-mentioned good practices, if adopted, should also be detailed in the law practice’s internal policy for consistency.

Conclusion

Handling client dissatisfaction effectively should be a priority for law practices, as it will help to conserve the law practice’s time and resources in the long run with fewer or no complaints being escalated to more formal avenues that are set out in the Legal Profession Act.17See Section 10.7.3 of the Guide. A proper complaints procedure “may help to quell the client’s feelings of dissatisfaction and therefore reduce the risk of further complaints, claims or damage to the firm’s reputation”.18Supra, n 6. Accordingly, law practices should educate their lawyers and staff on their internal complaints handling policies and procedures, so that everyone is on the same page in addressing the concerns of a dissatisfied client professionally and systematically.

Endnotes

| ↑1 | Solicitors Regulation Authority, Risk Outlook 2020/21 (23 November 2020) < https://www.sra.org.uk/sra/how-we-work/reports/first-tier-complaints-2019/> (accessed 18 March 2021). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ibid. |

| ↑3 | <https://www.lawsociety.org.sg/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Practice-Management-Guide-2017.pdf> (accessed 18 March 2021). |

| ↑4 | See Section 10.7 and Appendix 10A at pp. 116-118 of the Guide. |

| ↑5 | In identifying these good practices, the author had also reviewed a number of sources, including the complaints handling procedures published on the websites of a number of UK law firms. Other sources are identified in the subsequent endnotes. |

| ↑6 | Tracey Calvert, Anthony E Davis and Richard Harrison, “Review processes and client satisfaction: handling high-risk cases” in Hermann J Knott (ed.), Risk Management in Law Firms (Globe Business Publishing, 2014), para 5.2 at p 140. |

| ↑7 | Law Society of England and Wales, “Handling complaints” (Practice Note) (19 February 2021) at Section 6.1 <https://www.lawsociety.org.uk/en/topics/client-care/handling-complaints> (accessed 18 March 2021). |

| ↑8 | Supra, n 6 and n 7. |

| ↑9 | Supra, n 6 and n 7 (at Section 6.4). |

| ↑10 | Rebecca Atkinson, Assessing and Addressing Risk and Compliance in Your Law Firm (The Law Society, 2020), para 1.1.3 at p 4. |

| ↑11 | Supra, n 7 at Section 2. |

| ↑12 | Ibid. |

| ↑13 | Supra, n 10, para 1.1.2 at p 4. |

| ↑14 | Ibid. |

| ↑15 | Supra, n 7 at Section 6.3. |

| ↑16 | Ibid. |

| ↑17 | See Section 10.7.3 of the Guide. |

| ↑18 | Supra, n 6. |