Raise Your Ethics IQ … with the Professional Ethics Digest 2020

“The market value of a lawyer is inextricably linked with the non-negotiable calling card of integrity and ethical propriety. The Law Society is finalising a sequel to the 2019 Professional Ethics Digest to be released this quarter. That will contain additional relevant illustrations of the Professional Conduct Rules 2015 drawn from an anonymised version of members’ guidance given by the Advisory Committee of the Professional Conduct Council.”

Mr Gregory Vijayendran, SC, President of the Law Society, Opening of the Legal Year, 11 January 2021

Following the successful publication of the Professional Ethics Digest 2019 (the 2019 Digest)1The 2019 Digest covered guidances rendered by the Advisory Committee from November 2015 to April 2018. A soft copy of the 2019 Digest is available in the Members’ Library section of the Law Society’s website. in July 2019, the Law Society will be publishing the Professional Ethics Digest 2020 (the 2020 Digest) in late March 2021. The 2020 Digest comprises summaries of 27 guidances rendered by the Advisory Committee of the Professional Conduct Council (the Advisory Committee) between May 2018 and December 2019 that are of general application or interest to legal practitioners. These illustrations of the Legal Profession (Professional Conduct) Rules 2015 (PCR) are based on actual queries submitted by legal practitioners to the Advisory Committee for guidance.

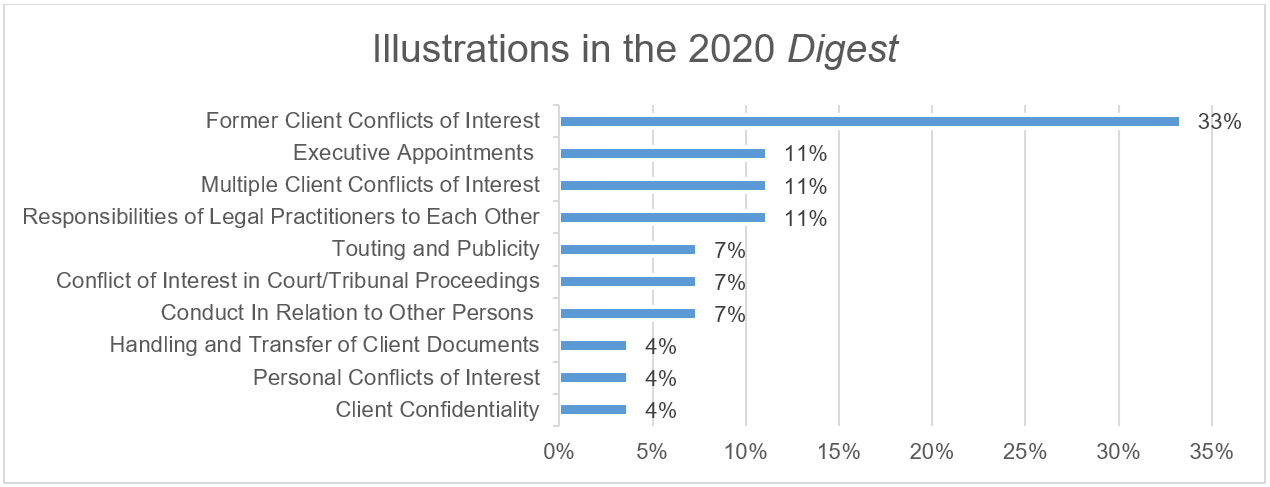

Overview of the Contents of the 2020 Digest

The diagram below provides a snapshot of the ethical issues covered in the 2020 Digest, with former client conflicts of interest clearly being the most common ethical issue during the period of coverage.

Whilst the illustrations in the 2020 Digest are naturally not representative of the frequency or importance of ethical issues encountered in practice, this article highlights five areas from the 2020 Digest that legal practitioners should pay special attention to.

Whilst the illustrations in the 2020 Digest are naturally not representative of the frequency or importance of ethical issues encountered in practice, this article highlights five areas from the 2020 Digest that legal practitioners should pay special attention to.

1. Former client conflicts of interest

The nine illustrations in the 2020 Digest on former client conflicts of interest (Illustrations 12 to 20) span a wide spectrum of practice areas, namely matrimonial, property, civil and commercial litigation as well as corporate. A common question concerned the application of rule 21(2) of the PCR, namely whether the legal practitioner in question had acquired the former client’s confidential information and whether such information might reasonably be expected to be material to the legal practitioner’s representation of the current client. Illustration 14 is particularly instructive in this regard.

Another important area is the standard of information barriers required under rule 21(4) of the PCR, which provides, inter alia, that “adequate safeguards” must be put in place to protect the former client’s confidential information. As Illustration 15 points out, recent Singapore case law and academic commentary have provided some general pointers on this issue, but there is to date no judicial authority that has definitively stipulated the standard of “adequate safeguards” required under rule 21(4)(a) of the PCR. Given the fact-specific nature of this inquiry (where factors such as the size and organisation of the law practice are likely to be relevant), legal practitioners should exercise caution in assessing the adequacy of their information barriers, in view of the “broader public interest” rationale that underpins rule 21 of the PCR.2See e.g. Harsha Rajkumar Mirpuri (Mrs) née Subita Shewakram Samtani v Shanti Shewakram Samtani Mrs Shanti Haresh Chugani (2018) 5 SLR 894 at (72).

2. Executive appointments

Similar to the 2019 Digest, questions on whether a legal practitioner can accept certain executive appointments under rule 34 of the PCR remain popular in the 2020 Digest. Legal practitioners should take note of the Advisory Committee’s view that practising solicitors should devote their professional time, energy and attention fully and solely to the practice of law, in keeping with the dignity of the profession. This is a common thread that runs through Illustrations 23 to 25 of the 2020 Digest.

3. Personal conflicts of interest

Recent case law has highlighted the thorny issues that can arise where a legal practitioner’s personal interest in the client’s matter is in conflict with the client’s best interests.3See e.g. Law Society of Singapore v Tan Chun Chuen Malcolm (2020) 5 SLR 946 and Law Society of Singapore v Govindan Balan Nair (2020) 5 SLR 988. Where an “adverse” interest exists under rule 22(3)(a) or rule 22(4)(a) of the PCR, the legal practitioner or law practice must comply with the procedure set out in the above-mentioned rules before the legal practitioner or law practice can act, or continue to act, for the client. This procedure requires the legal practitioner or law practice to: (i) make full and frank disclosure to the client of the adverse interest; (ii) advise the client to obtain independent legal advice (or otherwise ensure that the client is not under the impression that the client’s interests are being protected); and (iii) obtain the client’s written informed consent. Even where there is no adverse interest, rules 22(3)(b) and 22(4)(b) of the PCR prescribe that full and frank disclosure of the interest must be made and that the client’s written informed consent must be given.

Illustration 21 of the 2020 Digest provides a useful case study to consider the application of rule 22 of the PCR. Although the Advisory Committee had considered the enquiry under the rubric of rules 22(3)(b) and 22(4)(b) of the PCR, recent case law (as mentioned above) suggests that it should be reassessed under rules 22(3)(a) and 22(4)(a) of the PCR, in view of the broad meaning of an “adverse” interest which encompasses “any reason that would detract a legal practitioner from his duty to serve the best interests of his client”.4See Law Society of Singapore v Govindan Balan Nair (2020) 5 SLR 988 at (19). For a fuller exposition on the implications of the recent case law, legal practitioners should refer to the post-analysis at paragraphs 21.16 to 21.29 of the 2020 Digest.

4. Courtesy and fairness between legal practitioners

Illustrations 2 and 3 highlight a practical albeit unusual problem that some legal practitioners have encountered. Can a legal practitioner communicate directly with the opposing counsel’s client regarding court proceedings if the opposing counsel had been suspended from practice but is still on record representing the client?

Rule 7(3) of the PCR allows such direct contact in exceptional situations. For example, rule 7(3)(b) of the PCR provides where the legal practitioner has a reasonable basis to communicate directly with the opposing counsel’s client, and has taken reasonable steps to notify the opposing counsel of his or her intention, the legal practitioner may do so if the opposing counsel does not respond within a reasonable time after such notification. The Advisory Committee, however, cautioned that such communication with the opposing counsel’s client should be couched carefully, and that the legal practitioner should not be seen to be taking advantage of the circumstances.

A second scenario highlighted in Illustration 4 concerns the application of rule 29 of the PCR, which deals with making allegations against a fellow legal practitioner. The Advisory Committee noted that the reference to “another legal practitioner” in rule 29 is not limited to a legal practitioner acting for an opposing party, but can extend to a lawyer who had formerly advised the client of the legal practitioner making the allegation. The Advisory Committee also took the view that as rule 29 applies to pleadings (including a Defence), the response (or non-response) of the other legal practitioner to the allegations should be pleaded in the same document containing the allegations (which, in that case, was a Defence). This would ensure that the other legal practitioner is treated fairly and allow the Court to examine both the allegation and the response concurrently.

5. Touting and publicity

Legal practitioners should be mindful of the rules relating to touting and publicity found in Part 5 of the PCR, especially if they intend to publicise their law practice on a third party platform or together with third parties. Illustration 26 underscores various ethical considerations that the Advisory Committee took into account in giving guidance that publicising a law practice (alongside members of other industries or professions) through the medium of a deck of playing cards was not permissible. In particular, the potential to mislead recipients of the playing cards of the services provided by the law practice, as well as the impact of such a medium of publicity on the dignity of, and public confidence in, the legal profession, were critical to the Advisory Committee’s guidance.

Illustration 27 involved a law practice seeking to be featured (as one of a maximum of ten law practices) on an online marketplace platform in exchange for a fixed fee. The Advisory Committee expressed reservations about the nature and content of the publicity on the platform and cautioned the law practice to ensure that the users of the platform were not misled in compliance with Part 5 of the PCR. The Advisory Committee also advised the law practice to look cautiously into potential issues of touting, taking into account the relevant Law Society’s Practice Direction and Guidance Note.

Reader-friendly Features of the 2020 Digest

The 2020 Digest will be available as a downloadable pdf document from the Members’ Library section of the Law Society’s website as well as the new Ethics Resources page on the Law Society’s website. The 2020 Digest also comes with an index and various tables (of legislation, cases, and other sources referred to). It is envisaged that these additional features will greatly assist legal practitioners in navigating the 2020 Digest quickly.

Endnotes

| ↑1 | The 2019 Digest covered guidances rendered by the Advisory Committee from November 2015 to April 2018. A soft copy of the 2019 Digest is available in the Members’ Library section of the Law Society’s website. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See e.g. Harsha Rajkumar Mirpuri (Mrs) née Subita Shewakram Samtani v Shanti Shewakram Samtani Mrs Shanti Haresh Chugani (2018) 5 SLR 894 at (72). |

| ↑3 | See e.g. Law Society of Singapore v Tan Chun Chuen Malcolm (2020) 5 SLR 946 and Law Society of Singapore v Govindan Balan Nair (2020) 5 SLR 988. |

| ↑4 | See Law Society of Singapore v Govindan Balan Nair (2020) 5 SLR 988 at (19). |