Electronic Discovery and Cross-border Data Transfer

New Frontiers in Singapore, China, and Japan

Increasingly multi-national corporations in cross-border disputes are caught in a double bind – between the obligation to disclose information to an overseas authority under a legal request, and the duty to comply with domestic data transfer restrictions. Improper disclosures could attract serious criminal penalties. This article highlights the legal risks and case management practices relating to cross-border electronic data transfer (commonly known as “electronic discovery” or “eDiscovery”) involving Singapore, China,1 In this article, “China” and “PRC” are used interchangeably and refer to the People’s Republic of China, excluding the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau. and Japan.

Transfer Restrictions in Singapore, China, and Japan

Singapore, China, and Japan diverge considerably in their approaches to regulating cross-border data transfer. Singaporean and Japanese laws protects data privacy and cybersecurity, while recognising the business needs for cross-border transfer. Indeed, Japan has several data privacy initiatives to enhance the efficiency of cross-border dataflow.2 “New Initiatives for Ensuring Smooth Cross-Border Personal Data Flows” as published by the Japan’s Personal Information Protection Commission on 29 July 2016 at https://www.ppc.go.jp/files/pdf/280805_New_Initiatives_for_Ensuring_Smooth_Cross-Border_Personal_Data_Flows.pdf.

Chinese laws, by contrast, while protecting personal privacy, emphasizes national security interests and regulate data transfer with stringent but often vaguely worded laws. Many sets of implementation rules have been drafted but not yet commenced. The facts that China’s state-owned enterprises (“SOE”) dominates the economy and their data is often treated as state secrets heighten the compliance risks.

Singapore

Personal data privacy laws

In Singapore, the individual’s privacy right is well-recognized, as indicated in the recent public consultation by the Personal Data Protection Commission of Singapore (“Singapore Privacy Commission”).3 “Public Consultation for Approaches to Managing Personal Data in the Digital Economy” as published by the Singapore Privacy Commission on 27 July 2017 at https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/docs/default-source/public-consultation-5—act-review-1/public-consultation—approaches-to-managing-personal-data-in-the-digital-economy-(270717)f95e65c8844062038829ff0000d98b0f.pdf?sfvrsn=2. Singapore’s current regime comprises of the Personal Data Protection Act 2012 (“PDPA”) and the Personal Data Protection Regulations (“PDPR”), which became effective on 2 July 2014, the latter of which specifically expanded on, inter alia, requirements regarding cross-border data transfer. The PDPA defines “personal data” as data, whether true or not, about an individual who can be identified from that data, or from that data and other information to which the organization has or is likely to have access.4 Article 2 of the PDPA. Personal data may exist in electronic or other forms.5 Section 5.2 of the “Advisory Guidelines on Key Concepts in the Personal Data Protection Act” as revised by the Singapore Privacy Commission on 27 July 2017 at https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/docs/default-source/advisory-guidelines/advisory-guidelines-on-key-concepts-in-the-pdpa-(270717).pdf?sfvrsn=2.

Collection, use, and disclosure

The PDPA applies extraterritorially to all organisations, whether or not formed or recognised under the laws of Singapore or resident or having an office or a place of business in Singapore, unless specifically exempted.6 See Article 2 of the PDPA for the definition of “organisation” and Article 4 (1) of the PDPA for the application of the PDPA.

Under Article 13 of the PDPA, an organisation shall not collect, use, or disclose personal data unless the data subject gives, or is deemed to have given, his consent.7 Article 13(a) of the PDPA. Any collection, use, or disclosure shall be for purposes that a reasonable person would consider appropriate and has been informed of.8 Article 18 of the PDPA. Efforts shall be made to ensure that the personal data collected is accurate and complete,9 Article 23 of the PDPA. as well as secured to prevent unauthorized access, collection, and use, etc.10 Article 24 of the PDPA.

Transfer of personal data outside Singapore

The default rule is that no organization shall transfer any personal data outside of Singapore except in accordance with the PDPA or exempted by the Singapore Privacy Commission upon application.11 Article 26 of the PDPA. The PDPR expands on the requirement and allows cross-border data transfer, provided that the transferring organization takes appropriate steps to (i) ensure compliance with Parts III to VI of the PDPA; and (ii) ascertain that the recipient is bound by legally enforceable obligations of a jurisdiction with privacy protection standards comparable to that of Singapore.12 Article 9(1) of the PDPR. Criterion (ii) may be satisfied if the data subject consents to transfer to the said recipient in that jurisdiction.13 Article 9(3)(a) of the PDPR.

Anonymization/de-identification of data

According to the Advisory Guidelines on the Personal Data Protection Act for Selected Topics as issued by the Singapore Privacy Commission, data that has been anonymized is not personal data, and the general privacy requirements in Parts III to VI of the PDPA do not apply to the collection, use, or disclosure of such data.14 Section 3.4 of the Advisory Guidelines on the Personal Data Protection Act for Selected Topics as revised by the Singapore Privacy Commission on 28 March 2017 at https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/docs/default-source/advisory-guidelines—selected-topics/final-advisory-guidelines-on-pdpa-for-selected-topics-(28-march-2017).pdf?sfvrsn=2. Data would not be considered anonymized if there is a serious possibility that an individual could be re-identified.15 Section 3.3 of the Advisory Guidelines on the Personal Data Protection Act for Selected Topics. Examples of anonymization techniques include pseudonymization, aggregation, replacement, data suppression, data recoding or generalization, data shuffling, and masking.16 Section 3.9 of the Advisory Guidelines on the Personal Data Protection Act for Selected Topics. Organizations are responsible for their choice of techniques in anonymizing personal data.17 Section 3.10 of the Advisory Guidelines on the Personal Data Protection Act for Selected Topics.

Cybersecurity laws

The amended Computer Misuse and Cybersecurity Act (“CMCA”) became effective on 1 June 2017. Under section 8A, a new section of the amended CMCA, it is an offence to obtain, supply, or transmit personal information18 Note that “personal information” is not defined under the CMCA, and it is uncertain whether the definition of “personal data” in the PDPA could be relied on as reference in construing the same. that was obtained by an act done in contravention of some of the prohibitions under the CMCA, such as via unauthorized access to or modification of computer material.19 Article 8A of the CMCA. The amendment also applies extraterritorial effect to the provisions of the CMCA, expanding its scope to cover any person, whatever his nationality or citizenship, both outside and within Singapore.20 Article 11(1) of the CMCA.

China

State secrecy laws

China’s current Law on Guarding State Secret (中华人民共和国保守国家秘密法)21 In China, only the official Chinese versions of legislations have the force of law. All English translations is provided for the reader’s understanding and reference only. (“PRC State Secret Law”) and its Implementation Regulation became effective in 2010 and 2014, respectively.

“State secret” is defined broadly, as matters having a vital bearing on state security and national interests, such as “national economic and social development”.22 Article 9 of the PRC State Secret Law. Operational and technical information of central enterprises could also be classified as state secret.23 Article 3 of the Interim Requirements on the Protection of Trade Secrets of Central Enterprises (ä¸å¤®ä¼ä¸šå•†ä¸šç§˜å¯†ä¿æŠ¤æš‚行规定). Compliance with state secrecy laws in China is challenging because of its retroactive application, ambiguous procedures, and serious criminal penalties.

In the Xue Feng case, Xue was incarcerated in China for nearly eight years. Xue was found guilty for disclosing information to a U.S. company, which was classified retroactively as a “state secret” after he made the disclosure.24 See (1) http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-32180888; (2) https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-said-to-be-deporting-u-s-geologist-jailed-on-spy-charges-1428094957; (3) http://duihua.org/wp/?page_id=9603; and (4) https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704584804575644470575141314.

Under the PRC State Secret Law, no organisation or individual shall transfer state secret aboard without the approval of the governing department.25 Article 25(5) of the PRC State Secret Law. While the approval procedures are not clearly stated, the Implementation Regulation provides that individuals involved in the transfer of state secret must be PRC nationals.26 Article 29(2) of the Implementation Regulations of the PRC State Secret Law. China does not recognise dual nationality.27 Article 3 of the PRC Nationality Law (中华人民共和国国籍法).

Cybersecurity laws

Under the PRC Cybersecurity Law (中华人民共和国网络安全法), which became effective on 1 June 2017, any “personal information” and “important data” collected and produced by “critical information infrastructure operators” during their operation in China shall be stored within the jurisdiction, and any necessary cross-border provision arising from business needs shall be assessed pursuant governmental measures.28 Article 37 of the PRC Cybersecurity Law. The draft Measures for Security Assessment of Cross-Border Transfer of Personal Information and Important Data (个人信息和重要数据出境安全评估办法)),29 The draft Measures for Security Assessment of Cross-Border Transfer of Personal Information and Important Data was circulated for public consultation by the Cyberspace Administration of China on 11 April 2017, and it has been said that a revised draft has been presented for discussion on 19 May 2017 (see https://www.cov.com/-/media/files/corporate/publications/2017/05/china_releases_near_final_draft_of_regulation_on_cross_border_data_transfers.pdf). Since no official version of the revised draft has been made available, any discussion on the draft Measures in this article is based on the version released on 11 April 2017. if enacted in its current wording, will extend this requirement from “critical information infrastructure operators” to “network operators” or even all persons and entities, depending on its construction.30 Articles 2 and 16 of the draft Measures for Security Assessment of Cross-Border Transfer of Personal Information and Important Data.

“Personal information” is defined as all information, whether electronically recorded or otherwise, and whether taken alone or together with other information, that may identify a natural person.31 Article 76(5) of the PRC Cybersecurity Law and Article 17 of the draft Measures for Security Assessment of Cross-Border Transfer of Personal Information and Important Data. “Important data”, on the other hand, can be entirely anonymous — it is defined as data relevant to national security, economic development, and public interest of the society.32 Article 17 of the draft Measures for Security Assessment of Cross-Border Transfer of Personal Information and Important Data. In the draft Guidelines for Data Cross-Border Transfer Security Assessment (数据出境安全评估指南) circulated on 25 August 2017, industry-specific guidelines on the scope of important data have been set out.

Personal data privacy laws

In China, Article 40 of the Constitution of the PRC (中华人民共和国宪法) and several sets of laws and regulations expressly protect privacy. Both the PRC Criminal and Civil Law prohibit the unlawful sale or provision of personal information.33 Article 253-1 of the PRC Criminal Law (中华人民共和国刑法) and Article 111 of the PRC General Provisions of the Civil Law (中华人民共和国民法总则).

The National Information Security Standardization Technical Committee (also known as “TC260”) has also circulated a draft Personal Information Security Specification (个人信息安全规范) (draft “PI Security Specification”) and Guide for De-Identifying Personal Information (个人信息去标识化指南) on 29 May 2017 and 15 August 2017 respectively. Under the draft PI Security Specification, “personal information” and “personal sensitive information” have been defined extensively for the first time, the handling of which shall follow the principles of (1) consistent rights and responsibilities, (2) clear purpose, (3) choice and consent, (4) minimal and necessary uses, (5) openness and transparency, (6) security assurance, and (7) data subject participation.34 Article 4 of the draft Personal Information Security Specification.

Japan

Personal data privacy laws

The amended Act on the Protection of Personal Information (個人情報の保護に関する法律) (“APPI”) became fully effective on 30 May 2017, and clarified the definition of “personal information” to mean information relating to a living individual including those containing his name, address, or date of birth, and those containing an individual identification code.35 Article 2(1) of the amended APPI. Information relating to race, creed, social status, medical history, criminal record, the fact of having suffered damage by a crime, or other descriptions prescribed by cabinet order has been classified as “personal information requiring special care” (“PISC”).36 Article 2(3) of the amended APPI. The obtaining of PISC requires prior consent from the data subject.37 Article 17(2) of the amended APPI.

Third-party provision

Business operators shall not provide personal data to a third-party without prior consent of the data subject,38 Article 23(1) of the amended APPI. unless they have informed the data subject of the following and notified the Personal Information Protection Commission of Japan (“Japan Privacy Commission”): (1) one of the utilization purposes is third-party provision; (2) the categories of personal data to be provided; (3) the method of third-party provision; (4) the right of the data subject to request for the cessation of third-party provision; and (5) method for making the said request (“Opt-out Regime”).39 Article 23(2) of the amended APPI. Note that the Opt-out Regime is inapplicable to PISC.40 Article 17(2) of the amended APPI. Any third-party provision shall be recorded.41 Article 25 of the amended APPI.

Cross-border data transfer

For cross-border data transfer, the amended APPI provides that the data subject’s prior consent is required, except for transfer to a third-party with a system conforming to standards prescribed by the Japan Privacy Commission, or to a jurisdiction with privacy protection standards equivalent to that of Japan.42 Article 24 of the amended APPI. The said requirement has extraterritorial effect and applies to a business operator in a foreign jurisdiction who has acquired personal information in the course of supplying goods or services to a person in Japan.43 Article 75 of the amended APPI.

Anonymization/de-identification of data

In order to enhance dataflow, the amended APPI provides a new framework regulating “anonymously processed information”. The amended APPI, defines anonymously processed information as personal information that upon processing can neither be used to identify a specific individual nor to restore the personal information.44 Article 2(9) of the amended APPI. The said processing shall meet the standards as prescribed by the Japan Privacy Commission.45 Article 36(1) of the amended APPI. A business operator may provide anonymously processed information to a third-party, provided that it (1) discloses to the public in advance the categories of personal information contained in the anonymized data; and (2) notifies the receiving party of the anonymization under the rules of the Japan Privacy Commission.46 Article 37 of the amended APPI.

Cybersecurity laws

Japanese cybersecurity laws regulate data transfer. Under the Basic Act on the Formation of an Advanced Information and Telecommunications Network Society (高度情報通信ネットワーク社会形成基本法), actions shall be taken to ensure the security and reliability of advanced information and telecommunications networks and protect personal information.47 Article 22 of the Basic Act on the Formation of an Advanced Information and Telecommunications Network Society. The Basic Act on Cybersecurity (サイバーセキュリティ基本法) obliges critical information infrastructure operators, cyberspace related business entities, and other business entities to ensure cybersecurity and corporate with applicable government authorities.48 Articles 6 & 7 of the Basic Act on Cybersecurity. The Basic Act on the Advancement of Utilizing Public and Private Sector Data (官民データ活用推進基本法), which primarily aims to advance the appropriate use and effective circulation of data, also protects individuals’ rights to data privacy.49 Article 3 of the Basic Act on the Advancement of Utilizing Public and Private Sector Data.

Trade secret laws

The amended Unfair Competition Prevention Act (不正競争防止法) (“UCPA”) became effective on 1 January 2016. The amended UCPA defines “trade secret” as technical or business information useful for business activities, such as manufacturing or marketing methods, that is kept secret and that is not publicly known.50 Article 2(6) of the amended UCPA. No one shall use or disclose trade secrets obtained through wrongful means.51 Article 2(1)(iv) and Chapters 2 & 5 of the amended UCPA.

Risk Management Approaches

Each cross-border eDiscovery case has its own nuanced set of challenges: the storage location of the data; the variety of devices for preservation and collection; the data volume and file types for processing; the technical, linguistic, and other qualifications of experts handling and reviewing the information; the production requirements of requesting authorities and parties, etc. These impact on a party’s ability to meet cost and time constraints, and it is common for counsel to instruct eDiscovery specialists to conduct, with forensically sound practices, the collection, processing, review, and production. While addressing the relevant data laws and factors above, in our experience, clients and their counsel adopt broadly one of two approaches to manage risks where cross-border data transfer is necessary in their eDiscovery:

In-Country Solution

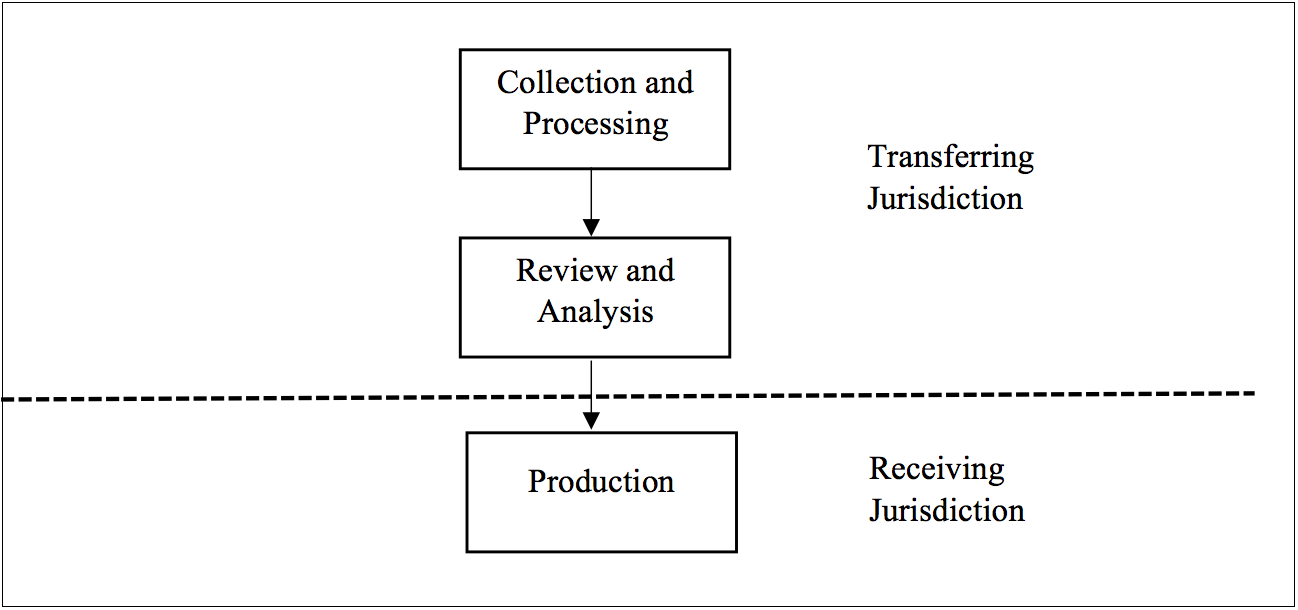

For projects where the data is located in a jurisdiction with transfer restrictions (“transferring jurisdiction”) and production of the same is required in another jurisdiction (“receiving jurisdiction”), a conservative approach is to conduct the collection, processing, and review within the transferring jurisdiction. Before transferring to and producing in the receiving jurisdiction, the disclosing party’s counsel, who are duly qualified in the transferring jurisdiction, would sign off on transfer of the reviewed documents for relevancy (with any applicable redaction and anonymization), and withhold documents subject to legal claims against disclosure. This approach is typically termed an “in-country solution” (see Exhibit 1), and data is hosted on servers local to the transferring jurisdiction. Where the risk level warrants a securer treatment, any or all the steps within the transferring jurisdiction could be conducted strictly within the disclosing party’s premises with offline mobile eDiscovery technologies.

Exhibit 1 – In-Country Solution

“Mix and Match”

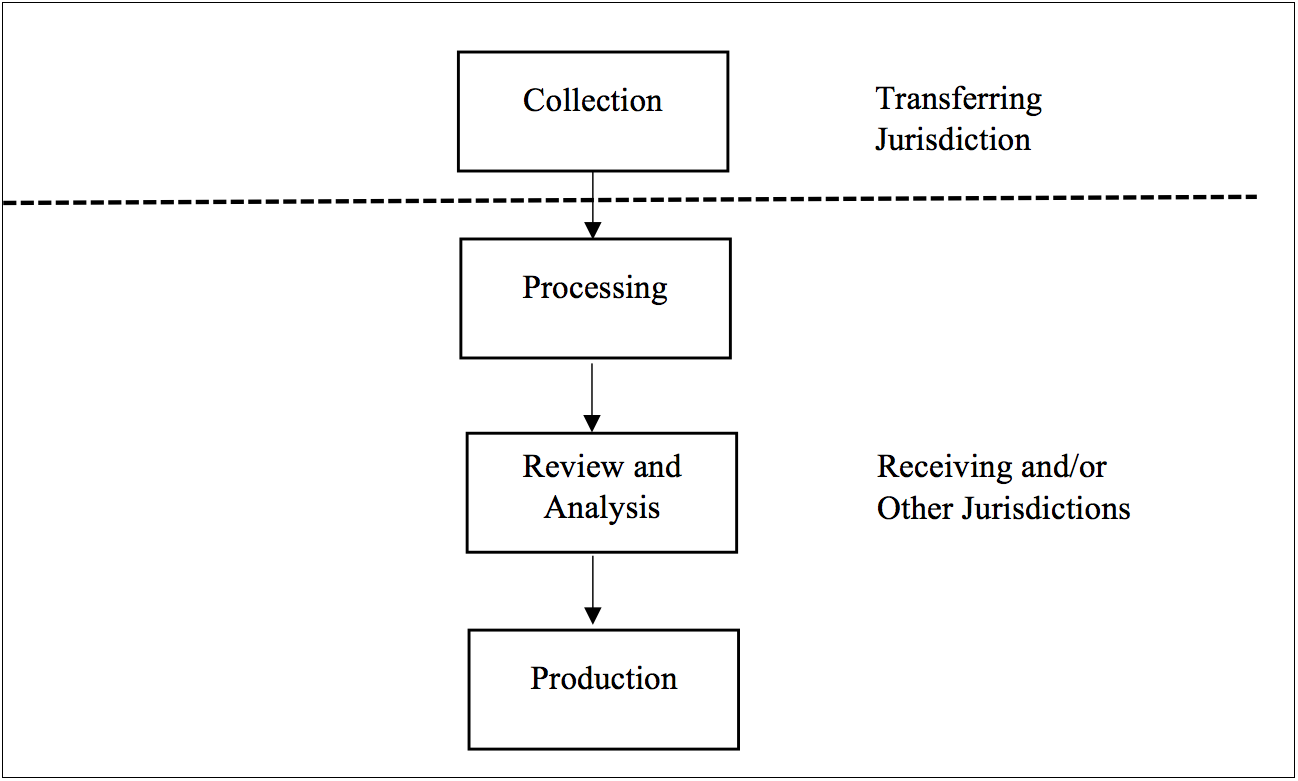

It is not uncommon in eDiscovery cases where only the data collection is completed in the transferring jurisdiction (see Exhibit 2). Some eDiscovery vendors could provide cost efficiencies if particular processing and review steps were completed offshore or near-shore before production in the receiving jurisdiction. With counsel advising and eDiscovery specialists assisting, certain disclosing parties might internalize some of the review, transfer, and other eDiscovery steps, especially if they have offices in both the transferring and receiving jurisdictions. Cloud-based eDiscovery technologies support the de-localization of data, which provide further cost efficiencies. However, the degree of flexibility in managing eDiscovery workflow and dataflow ultimately depends on the applicable laws. Certainly, local counsel’s advice on key concepts, rules, and exemptions are essential in preparing the eDiscovery case; for example, how does the applicable law treat data processing and what kinds of action constitute transfer, access, and use, etc.

Exhibit 2 – Out-Country Solution

Conclusion

Data transfer laws are complex and diverse, and further legislative reforms in Singapore, China, and Japan is expected. These trends will require extra vigilance in conducting eDiscovery, because any breach could result in severe penalties. When conducted with compliance and efficiency, eDiscovery solutions could help save costs and time, reduce human error, and help counsel find the needle in the proverbial – multi-jurisdictional – haystack.

Endnotes

| ↑1 | In this article, “China” and “PRC” are used interchangeably and refer to the People’s Republic of China, excluding the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “New Initiatives for Ensuring Smooth Cross-Border Personal Data Flows” as published by the Japan’s Personal Information Protection Commission on 29 July 2016 at https://www.ppc.go.jp/files/pdf/280805_New_Initiatives_for_Ensuring_Smooth_Cross-Border_Personal_Data_Flows.pdf. |

| ↑3 | “Public Consultation for Approaches to Managing Personal Data in the Digital Economy” as published by the Singapore Privacy Commission on 27 July 2017 at https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/docs/default-source/public-consultation-5—act-review-1/public-consultation—approaches-to-managing-personal-data-in-the-digital-economy-(270717)f95e65c8844062038829ff0000d98b0f.pdf?sfvrsn=2. |

| ↑4 | Article 2 of the PDPA. |

| ↑5 | Section 5.2 of the “Advisory Guidelines on Key Concepts in the Personal Data Protection Act” as revised by the Singapore Privacy Commission on 27 July 2017 at https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/docs/default-source/advisory-guidelines/advisory-guidelines-on-key-concepts-in-the-pdpa-(270717).pdf?sfvrsn=2. |

| ↑6 | See Article 2 of the PDPA for the definition of “organisation” and Article 4 (1) of the PDPA for the application of the PDPA. |

| ↑7 | Article 13(a) of the PDPA. |

| ↑8 | Article 18 of the PDPA. |

| ↑9 | Article 23 of the PDPA. |

| ↑10 | Article 24 of the PDPA. |

| ↑11 | Article 26 of the PDPA. |

| ↑12 | Article 9(1) of the PDPR. |

| ↑13 | Article 9(3)(a) of the PDPR. |

| ↑14 | Section 3.4 of the Advisory Guidelines on the Personal Data Protection Act for Selected Topics as revised by the Singapore Privacy Commission on 28 March 2017 at https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/docs/default-source/advisory-guidelines—selected-topics/final-advisory-guidelines-on-pdpa-for-selected-topics-(28-march-2017).pdf?sfvrsn=2. |

| ↑15 | Section 3.3 of the Advisory Guidelines on the Personal Data Protection Act for Selected Topics. |

| ↑16 | Section 3.9 of the Advisory Guidelines on the Personal Data Protection Act for Selected Topics. |

| ↑17 | Section 3.10 of the Advisory Guidelines on the Personal Data Protection Act for Selected Topics. |

| ↑18 | Note that “personal information” is not defined under the CMCA, and it is uncertain whether the definition of “personal data” in the PDPA could be relied on as reference in construing the same. |

| ↑19 | Article 8A of the CMCA. |

| ↑20 | Article 11(1) of the CMCA. |

| ↑21 | In China, only the official Chinese versions of legislations have the force of law. All English translations is provided for the reader’s understanding and reference only. |

| ↑22 | Article 9 of the PRC State Secret Law. |

| ↑23 | Article 3 of the Interim Requirements on the Protection of Trade Secrets of Central Enterprises (ä¸å¤®ä¼ä¸šå•†ä¸šç§˜å¯†ä¿æŠ¤æš‚行规定). |

| ↑24 | See (1) http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-32180888; (2) https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-said-to-be-deporting-u-s-geologist-jailed-on-spy-charges-1428094957; (3) http://duihua.org/wp/?page_id=9603; and (4) https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704584804575644470575141314. |

| ↑25 | Article 25(5) of the PRC State Secret Law. |

| ↑26 | Article 29(2) of the Implementation Regulations of the PRC State Secret Law. |

| ↑27 | Article 3 of the PRC Nationality Law (中华人民共和国国籍法). |

| ↑28 | Article 37 of the PRC Cybersecurity Law. |

| ↑29 | The draft Measures for Security Assessment of Cross-Border Transfer of Personal Information and Important Data was circulated for public consultation by the Cyberspace Administration of China on 11 April 2017, and it has been said that a revised draft has been presented for discussion on 19 May 2017 (see https://www.cov.com/-/media/files/corporate/publications/2017/05/china_releases_near_final_draft_of_regulation_on_cross_border_data_transfers.pdf). Since no official version of the revised draft has been made available, any discussion on the draft Measures in this article is based on the version released on 11 April 2017. |

| ↑30 | Articles 2 and 16 of the draft Measures for Security Assessment of Cross-Border Transfer of Personal Information and Important Data. |

| ↑31 | Article 76(5) of the PRC Cybersecurity Law and Article 17 of the draft Measures for Security Assessment of Cross-Border Transfer of Personal Information and Important Data. |

| ↑32 | Article 17 of the draft Measures for Security Assessment of Cross-Border Transfer of Personal Information and Important Data. |

| ↑33 | Article 253-1 of the PRC Criminal Law (中华人民共和国刑法) and Article 111 of the PRC General Provisions of the Civil Law (中华人民共和国民法总则). |

| ↑34 | Article 4 of the draft Personal Information Security Specification. |

| ↑35 | Article 2(1) of the amended APPI. |

| ↑36 | Article 2(3) of the amended APPI. |

| ↑37 | Article 17(2) of the amended APPI. |

| ↑38 | Article 23(1) of the amended APPI. |

| ↑39 | Article 23(2) of the amended APPI. |

| ↑40 | Article 17(2) of the amended APPI. |

| ↑41 | Article 25 of the amended APPI. |

| ↑42 | Article 24 of the amended APPI. |

| ↑43 | Article 75 of the amended APPI. |

| ↑44 | Article 2(9) of the amended APPI. |

| ↑45 | Article 36(1) of the amended APPI. |

| ↑46 | Article 37 of the amended APPI. |

| ↑47 | Article 22 of the Basic Act on the Formation of an Advanced Information and Telecommunications Network Society. |

| ↑48 | Articles 6 & 7 of the Basic Act on Cybersecurity. |

| ↑49 | Article 3 of the Basic Act on the Advancement of Utilizing Public and Private Sector Data. |

| ↑50 | Article 2(6) of the amended UCPA. |

| ↑51 | Article 2(1)(iv) and Chapters 2 & 5 of the amended UCPA. |