Engaging and Working with a Forensic Expert

Insights from a Forensic Scientist

Introduction

Forensic analysis has emerged as a powerful tool for the justice system. Its unique ability to uncover the most vital piece of evidence can make or break a case. It can provide an objective explanation to complement, corroborate, challenge or refute lay witnesses’ accounts. The value that forensic science brings to a case depends on factors such as the area of contention, availability and quality of evidence, type of forensic testing performed, evaluation of the significance of the evidence to the case, and the examiner’s level of expertise and experience.

A “hopeless” case involving signature manipulation: A forensic document expert’s assistance in a case involving a disputed contract “vindicated” the Defendant, who was adamant that he did not sign the document. Only the reproduced copy was available for examination, as the Plaintiff claimed that the original copy was already in the Defendant’s custody. The Defendant’s lawyer assessed the situation and advised his client that little could be done, there being no evidence to suggest that the document was fraudulent. Even the Defendant was puzzled that the signatures in the multi-page document bore a striking resemblance to his signatures. The Defendant decided to engage a forensic expert even though he did not expect forensic analysis to yield useful results. To his relief, the forensic findings provided unequivocal evidence that the signatures on the contract were cut-and-paste manipulations, casting doubt on the authenticity of the contract.

An effective expert is a tag-team partner who complements the legal practitioner and assists in clarifying the significance and limitation of scientific evidence. The input of the expert can have a positive impact on the case strategy. Thus, engaging a suitable and befitting expert, and establishing good communication and professional rapport with the expert may be the deciding factors for a successful legal proceeding.

Finding a suitable forensic expert can be a challenge for legal practitioners – more so in areasunfamiliar to them. What should you look for in an expert? When and how should you engage an expert? The expert may appear to have impeccable credentials but apart from his qualifications, what traits should you expect in an effective expert witness? Besides making the technical findings clear, are there other aspects an expert can assist your case? How do you get the most out of the professional advice, the expert report and the expert testimony?

This article addresses these questions and more from the perspective of a forensic scientist. Together with the article “Staying Non-partisan – The Duty of An Expert”,1Staying non-partisan – the Duty of an Expert, Law Gazette, April 2019. the authors hope to provide legal practitioners with an effective road map to the selection and engagement of forensic experts to make the best out of their cases in mediation, arbitration and court proceedings.

How to Find an Expert

Finding a suitable expert with the relevant qualifications and expertise for a case may be a daunting task for the uninitiated. Expert directories and expert hiring agencies are more frequently used options overseas. Locally, legal practitioners commonly rely on one or more of the following sources:

- Experts whom the legal practitioner has worked with previously, or were engaged by the opposing party in past cases;

- “Word-of-mouth” i.e. referrals from fellow colleagues, or other contacts;

- Judgments from cases in which expert witnesses have testified;

- Professional organisations and associations; and

- The Law Society Specialist Services Directory and the Internet.

What to Look for in an Expert?

How do legal practitioners determine whether a forensic expert has the necessary qualifications in the specific area required?

Professional Qualifications and Expertise

When a lawyer scrutinises the curriculum vitae of experts to evaluate their credentials, besides checking that the forensic scientist has relevant educational qualifications, professional training, relevant forensic casework experience and membership in reputable professional organisations, he should look out for other aspects of professional qualifications such as:

- Continuous learning through attendance at forensic conferences, seminars, workshops and other courses,

- Provision of lectures and training in his area of expertise;

- Active involvement in research and development projects, as well as presentations at professional meetings and publication of the findings in scientific journals.

Selecting a suitable expert

- Engage your expert at an early stage in your case.

- Check your expert’s qualifications and the relevance of his expertise to your case.

- Ensure that your expert is credible, independent, objective, confident articulate and approachable.

Traits of an Effective Expert2Forensic Science, Briefs for the Legal Practitioner, Chapter 17, The Forensic Experts Group, 2017.

The expert must remain truthful and objective. It is not coincidental that before providing their testimonies, expert witnesses are first sworn in and they pledge then to tell “the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth”. An impartial and credible expert will include all his findings, whether or not they support, or are “of no value”, or even detrimental to the engaging party.

The expert must be cognisant of his duty to the court and the rules of the court and the judicial system within which he works. He must be aware of relevant contextual information and perceptive of contending issues in the case at hand to ensure that the report is relevant to them. Equipped with this knowledge, he will be better disposed to set out the purpose of his report, and structure it in a way that will more effectively answer the pertinent questions of the case.

“A mere opinion anyone can give, but an opinion based on accurate and intimate knowledge, if logically presented and adequately illustrated, will not only bear the fierce light that beats upon the witness box but will be clarified and strengthened the more it is attacked.”

– Albert S. Osborn

Effective experts recognise that the discovery of scientific facts is inadequate if it fails to assist the Court in recognising their significance. In other words, a highly qualified and competent expert may amount to little if he is unable to clearly convey his findings and opinion in the expert report or articulate his explanations to the Court in a logical and convincing manner. An expert opinion based on accurate knowledge and supported by findings will not only withstand court scrutiny3Albert S. Osborn, Questioned documents (2nd edition, 1929)., but will also gain acceptance and be well-received by the Court.

When Should You Engage an Expert?

When should a legal practitioner engage a forensic expert? After receiving an opposing expert report that is unfavourable to the client? After exhausting all means of a settlement for the client? Read on and you may likely reconsider your options for your next case.

Time is of the essence! Often, a legal practitioner may begin searching for an expert only when the court trial is imminent, only to realise that the expert may not be able to take on the case at short notice. Or worse, he is unable to find the relevant expert with the required expertise within the short time frame. To avoid such a situation and to achieve the best possible outcome for your case, it is more effective to find and retain an expert in the early stages of a case.

Consulting an expert early allows the legal practitioner to determine, develop or modify his case strategy, and the expert to study the case and conduct the analysis in good time. It also leaves the legal practitioner sufficient time to digest and fully understand the forensic report and prepare adequately for the court trial.

A “very late” request: A request for forensic analysis was made just before the Appeal process. The Appeal Judge indicated that the evidence should have been adduced during the court trial, and not at such a late stage during the Appeal. It was only due to special circumstances surrounding the case that the new evidence was admitted. The forensic report turned out to be favourable to the party engaging the forensic expert.

Why Do You Need an Expert?

As was aptly expressed by former Senior Judge Kan Ting Chiu,4Forensic Science, Briefs for the Legal Practitioner, Foreword, The Forensic Experts Group, 2017. knowledge is power: “[A lawyer’s] competence in law needs to be matched by a working knowledge of science”. Understanding the science behind an expert report, as well as what you do with the report, will impact your case.

Understanding an Expert Report

Forensic reports often contain technical jargon that is familiar only to someone trained in the same field. Understanding an expert report can be challenging due to difficult terminology or concepts. Unless the legal practitioner has previously worked on cases involving the same forensic area, reading and understanding the expert report can be a daunting task. Moreover, when an untrained eye reads an expert report, important details can be missed. It is a tall order to expect the legal practitioner to competently and thoroughly interpret all elements of a forensic report.

Proactive Approach Using Science Instead of Law

Engaging an expert after you have received an expert report from the opposing party is a reactive response. For certain cases, you may wish to take a step back and consider the option of approaching your case from a scientific perspective instead of a legal perspective. Just like the old legal aphorism, “If you have the facts on your side, pound the facts. If you have the law on your side, pound the law.” Be mindful that to take this approach, a legal practitioner must have knowledge of the relevant forensic disciplines and their value, and in the early stages of the case, tap on the knowledge and experience of an expert to determine the weight that science carries in his case strategy.

Giving the Client Peace of Mind

When faced with a potential criminal charge, a client is usually advised by his lawyer to commence actions only at a later stage when charges have been formalised. However, the client may still be worried and agonising over what might ensue. At this early stage, an expert can provide professional advice and conduct a preliminary assessment of the case.

How Does the Expert Assist You?

Making a More Informed Decision

A qualified and experienced forensic expert is a repository of scientific knowledge, able to provide insights to help the legal practitioner make more informed decisions that enhance his case strategy. Experts generally perform an independent analysis of the case, issue an expert report, conduct a critical review of another expert’s report to provide a second opinion, provide professional advice during pre-trial case preparation, and testify in court. The request for forensic consultancy at the onset of and throughout a case is less common.

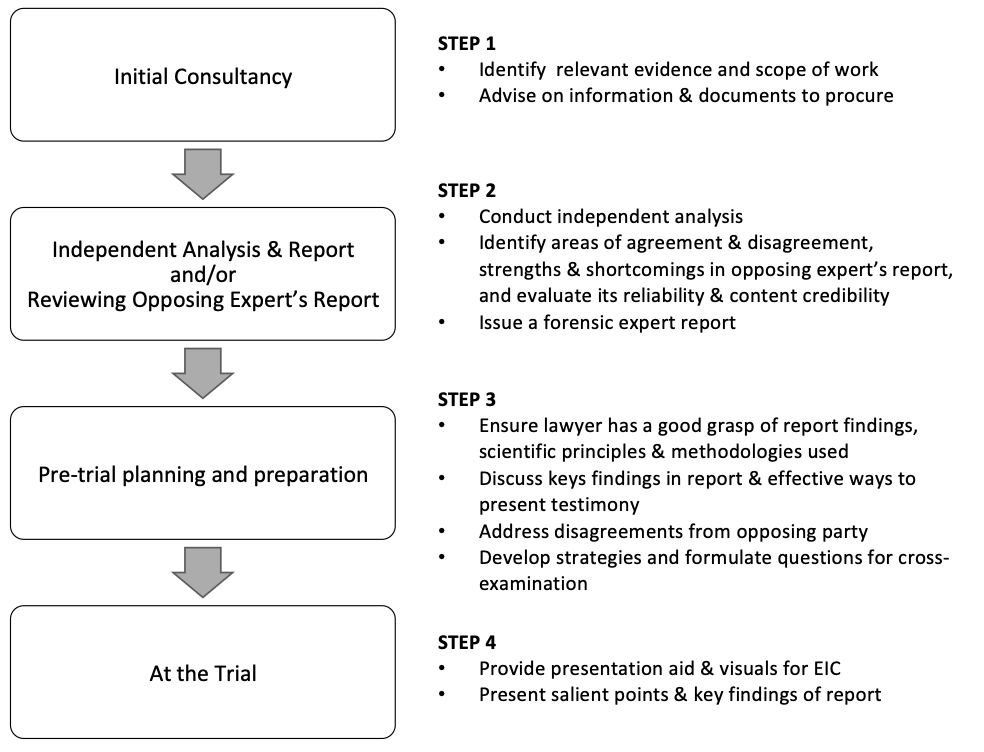

Initial Consultancy

The expert serves as a key resource person to advise the legal practitioner on the scope of forensic work, types of scientific evidence that may be useful, and relevant information and documents to procure for a preliminary assessment. Forewarned is forearmed: initial consultancy safeguards the legal practitioner from being caught unawares when an expert report is given at a late stage by the opposing party.

The preliminary assessment constitutes an introductory or exploratory phase where the expert identifies the overall strengths and weaknesses of the forensic evidence for the case. Initial findings are provided in a simplified concise form that indicates how probable a hypothesis may be. The initial consultancy may lead to the expert performing a comprehensive and more detailed analysis, preparing an independent analysis report or continuing with the consultancy as the resource expert.

Scouting for potential evidence: In a case involving numerous documents alleged to be fraudulent, forensic experts conducted a preliminary assessment to determine whether there were signs of tampering or irregularities and inconsistencies in the documents. The assessment enabled the experts to scope the work, select the relevant techniques for analysing the documents, and provide a quotation for the forensic report.

Helping the client reach a decision: In a road traffic accident case, forensic experts analysed the video recording recovered from the in-vehicle camera, calculated the speed of the vehicle, and advised the lawyer that the driver was driving at an excessive speed above the road speed limit when he collided with a cyclist. The driver subsequently decided to plead guilty to the charge of negligence.

Providing peace of mind: A client who was involved in a traffic collision was worried that he would be charged by the Traffic Police (TP) although he was quite certain that the other driver beat the red light. Despite his lawyer advising him to leave the matter aside till TP took further action, he approached forensic experts for professional advice and preliminary assessment of the case. The consultancy assisted in allaying the client’s worries.

Figure 1: How an expert can assist the legal practitioner

Preparing an Independent Expert Report

An expert is often engaged to provide an independent analysis of the case. Some cases require a site inspection to examine the scene or items that are in the custody and premises of the opposing party. Formal reports are written in anticipation that they will be tendered and admitted in court as evidence. To meet the standards, a forensic report must be objective, robust, transparent and balanced.

The report is communicated in concise, clear and unambiguous language. It may include a glossary of technical terms. Qualifiers, assumptions and limitations are clearly stated. Speculation must not be presented as fact, and opinions delineated from empirical factual findings.

For an expert report to maintain its objectivity, the legal practitioner should have no influence on the preparation of the report and should not vet or amend the wording – much less write the report for the expert. It is a no-no for an expert to provide draft reports to lawyers for comment and revision. At the onset of the engagement, both parties should have clarified and agreed on the purpose of the request, scope and extent of examinations, and key issues to address. If a new request is made, or if new evidence or information becomes available, the expert can perform additional examinations and issue a supplemental report or addendum.

Reviewing an Opposing Expert Report

It is paramount that your own expert be given the opportunity to review and advise you on every report that the opposing expert puts up, regardless of whether your expert has already issued a formal report. If you are confronted with an opposing report but have yet to engage your own expert, it would be wise to promptly engage one to independently assess the relevance and merits of the report.

The review process entails a thorough scientific evaluation of the report. Your expert will sift out the vital elements in the report and point out the significance and implications of the findings, and insofar as the report details allow, ascertain whether relevant evidence was adequately considered or overlooked. A good expert will critically evaluate the reliability and content credibility by checking their basis, the soundness of the methodology, lines of reasoning and coherence of the report. The review would identify and report areas of scientific agreement and disagreement, the strengths and limitations of the report, and any potential issues and shortcomings. The expert assists the legal practitioner in formulating questions and developing strategies for cross-examination.

Pre-trial Case Planning and Preparation

The teamwork and rapport between the legal practitioner and the forensic expert begins before the trial. Two types of pre-trial preparation are common: the first type entails discussion of key findings in the forensic reports issued by both experts, as well as planning how best to present court testimony, and address disagreements from the opposing party’s lawyer and expert. The second type pertains to expert consultancy on the case without the expert going on the witness stand. As a scientific resource person, besides assisting during pre-trial preparation, the forensic expert may also be present during the trial to provide professional advice to the legal practitioner, and mainly during cross-examination of the opposing expert.

Building Rapport

Since each case is unique, there is no one-size-fits-all approach or fixed sequence to maximise expert testimony in the courtroom. In most cases, pre-trial preparation between the legal practitioner and forensic expert is essential to laying the groundwork for an effective court trial. The lawyer and the expert should have a common understanding on how best to present the expert evidence and testimony in Court. This understanding and rapport between the legal practitioner and the expert may make the difference between a powerful testimony and a weak one. The forensic expert must be ever mindful of the importance of remaining scientifically independent while maintaining close interactions with the legal practitioner.

Having a good grasp of the report findings

During the pre-trial preparation meeting, the expert helps the legal practitioner understand the basic scientific principles and methodology of the forensic discipline and ensures that he has a good grasp of both experts’ findings and conclusions, and their significance, strengths and limitations. This crash course helps ensure that the legal practitioner has a working knowledge of the forensic findings. It prepares the legal practitioner to ask the correct and relevant questions for a logical, effective delivery of the expert testimony. Awareness of the weaknesses and limitations of the evidence also prevents the lawyer from being caught off-guard during the trial. He will be in a stronger position to maintain his line of questioning during cross-examination, anticipate responses, detect inconsistencies, and formulate appropriate re-examination questions to clarify and correct misguided notions brought up during cross-examination.

At the Trial

In most EICs, the legal practitioner would take the expert witness through a “step-by-step question-and-answer” approach whereby the former asks a question in order to state or clarify a finding to which the expert answers, and the process is repeated.

On the other hand, for complicated or complex cases, the expert may be given “free rein” to present in practically uninterrupted manner the salient points and key findings of his report. The expert may spend considerable time explaining the methodology used and the basis of his findings and conclusions during EIC.

Presentation aids and visuals greatly increase the effectiveness of the technical testimony and reduces the time and effort of the Court to understand and appreciate the evidence. The impact and usefulness of this approach should not be underestimated, even if the opposing party does not challenge the report findings. Nothing beats having the Court “see” the evidence during the presentation of the expert testimony.

Overcoming Challenges and Limitations

Trust, but Verify

In criminal proceedings, the defence expert is often engaged only at a much later stage of the case; many a time, close to the trial date. His role is often limited to explaining the prosecution expert’s report to the defence counsel and reviewing its entirety for accuracy and reliability. He is not able to perform first-hand examination of evidential items which are held in police custody. The defence expert is disadvantaged because he sees only the final report, and is obliged to view evidence through the lenses of others; there may be times when important details may have been missed out or misinterpreted.

Despite the possibility of shortcomings and areas of concern in an opposing expert’s report, defence counsels may not be keen or are unable to engage their own experts to conduct an independent analysis of the evidence as they may consider that the legal burden of proof lies with prosecution, and for the most part, their clients lack the necessary funds. This unfortunately deprives the justice system of much-needed checks and balances to weed out errors in forensic science. The Russian proverb “Trust, but verify” applies to this legal situation as science is not absolute, and no system is perfect.

Saving Resources for the Authority and Reducing Cost for the Client

Experts may also face the challenge of restricted or delayed access to essential documents such as police scene photographs, sketch plans, video recordings, statements of witnesses, and expert reports. For example, the Traffic Police charge $55 for a 5R-size TP photograph of the incident scene. A full set of photographs typically cost a few thousand dollars – a hefty sum that must be paid even before engaging a lawyer and an expert. It is no wonder that clients choose to purchase only a few photographs instead of the full set without realising that in doing so, they may be prejudicing their case.

A beneficial alternative is for the TP to consider providing soft copies of the scene photographs in a CD format. This option saves printing resources for the TP and will be much more viable and affordable for the client.

Professional Advice on Work Scope by SJE During PTC

In Single Joint Expert trials, considerable time may be spent agreeing on joint instructions. The expert may thus bear the cost and burden of seeking and providing clarifications and replies, toing and froing with both parties. Formal correspondence between the expert and parties can be long-drawn, incurring time and resources that neither party is willing to bear. As Singapore adopts a new approach to improve the delivery of expert evidence, we can learn from the challenges faced by overseas counterparts and take steps to modify and improve the approach.

For cases with contentious issues, it may be beneficial to involve the appointed expert at the pre-trial conference (PTC) to provide advice on the scope of analysis to both parties and the Court, taking into consideration the relevant contextual information and diametrically opposing issues.

Conclusions

An effective expert is competent, honest, credible, confident and able to provide expert testimony objectively and convincingly in court. Not only can the qualified expert independently examine physical evidence, report findings and conclusions, and testify in court, he can also provide the legal practitioner with initial consultancy on the potential use of forensics for the case, assist the lawyer in understanding an opposing expert’s report, and develop strategies with the lawyer in cross-examining the opposing expert.

Whilst being mindful of the requirement to remain scientifically independent and impartial, the forensic expert must also maintain a constructive professional relationship with the legal practitioner. This partnership begins long before the court trial. In fact, the legal practitioner should engage the forensic expert as early as possible, and both of them should make effort to foster communication and understanding, and build good working rapport.

In essence, a competent expert is an invaluable asset who will help the legal practitioner gain insight into the forensics involved in the case. Engaging a qualified and befitting expert at an early stage in your case can be pivotal to the success of the legal proceeding.

Endnotes

| ↑1 | Staying non-partisan – the Duty of an Expert, Law Gazette, April 2019. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Forensic Science, Briefs for the Legal Practitioner, Chapter 17, The Forensic Experts Group, 2017. |

| ↑3 | Albert S. Osborn, Questioned documents (2nd edition, 1929). |

| ↑4 | Forensic Science, Briefs for the Legal Practitioner, Foreword, The Forensic Experts Group, 2017. |