Developing the Inner Art of Lawyering

By the time you read this article, the law practice that you are or will be practising in would have received a complimentary copy of the Professional Ethics Digest 2019 (the Digest), published by the Law Society. The Digest compiles relevant illustrations of the application of the Legal Profession (Professional Conduct) Rules 2015 (PCR) based on actual queries submitted by lawyers to the Advisory Committee of the Professional Conduct Council.

As a newly admitted lawyer, the Digest is an important resource for you to understand better the ethical terrain of legal practice that you are or will soon be navigating in. In addition, the Digest is a critical step to developing the inner art of lawyering.

What is the inner art of lawyering, you may ask? For much of your legal education so far, the focus has been spent on developing the external art of lawyering, which includes advocacy techniques, drafting skills and substantive law expertise. These are necessary building blocks to shaping you as a lawyer who is able to advise and represent your clients competently. Equally important is to develop your internal ethical decision-making processes so that you can make optimal ethical decisions. Just as you will need to continually update and upgrade your legal knowledge and skills throughout your legal career, the inner art of lawyering is for the long haul and needs to be regularly refreshed.

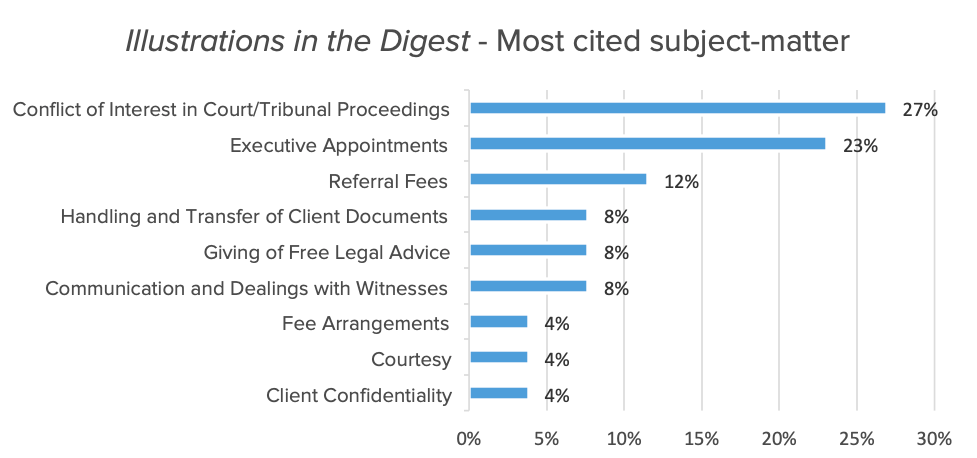

Using the Digest as a starting point, let’s look at some of the common ethical issues that you are likely to encounter in your early years of practice. In total, the Digest provides 26 illustrations which are categorised according to subject-matter as shown in the diagram below:

At a glance, the most common ethics query cited in the Digest concerns conflict of interest in court/tribunal proceedings, which is followed closely by queries on executive appointments and referral fees. Though by no means representative of the frequency or importance of ethical issues encountered in practice, the Digest provides a rough gauge of the more difficult ethical issues that you or your law practice is likely to face. We will look at four issues which will probably crop up more regularly in your early years of practice: conflict of interest, giving of free legal advice, client confidentiality and courtesy.

At a glance, the most common ethics query cited in the Digest concerns conflict of interest in court/tribunal proceedings, which is followed closely by queries on executive appointments and referral fees. Though by no means representative of the frequency or importance of ethical issues encountered in practice, the Digest provides a rough gauge of the more difficult ethical issues that you or your law practice is likely to face. We will look at four issues which will probably crop up more regularly in your early years of practice: conflict of interest, giving of free legal advice, client confidentiality and courtesy.

Conflict of Interest

For those of you in litigation practice, it pays to study Illustrations 3 to 9 in the Digest carefully. They include several cases involving possible former client conflicts under rule 21 of the PCR, when a lawyer or law practice acts or intends to act for a client whose interests are adverse to those of the law practice’s former client. Former client conflicts may also feature when a lawyer moves to another law practice (see Illustration 5).

At the heart of such conflicts is the fear of disclosure of the former client’s confidential information to the current client. Such conflicts may also trigger consideration of other ethical rules, such as the prohibition against being a witness on material issues in proceedings under rule 11(3) of the PCR (see Illustrations 6, 7 and 8).

If you are faced with a potential former client conflict, you should take a step-by-step approach in analysing your ethical obligations as outlined by the Advisory Committee (see e.g. Illustration 5). In particular, the Advisory Committee has helpfully observed that whether a party alleged to be in conflict possesses material confidential information belonging to the former client is a question of fact and a lack of supporting particulars in this regard would be considered in ascertaining whether a conflict of interest exists (see Illustration 8, para (a) under “Guidance”).

Apart from the Illustrations in the Digest, you should also be mindful that the Court of Three Judges had, in a recent disciplinary case, highlighted the potential sanctions for breaches of different categories of conflict of interest rules.1Law Society of Singapore v Ezekiel Peter Latimer (2019) SGHC 92.

Giving of Free Legal Advice

If you are involved in pro bono work in legal clinics, you would be aware that rule 47(3)(b) of the PCR provides that you cannot act for any person to whom you have given free legal advice, unless you act for that person in a pro bono capacity. You are also required to take reasonable steps under rule 47(2) of the PCR to ensure that if any information is publicised to the pro bono client, only your name, the fact that you are a legal practitioner and the name of your law practice can be disclosed. Business cards or marketing collaterals relating to your law practice cannot be distributed in the course of giving free legal advice at legal clinics.2See rule 47(3)(a) of the PCR.

The Digest highlights a typical ethical problem posed by a pro bono client seeking to retain the lawyer’s services on a paid basis following a consultation at a pro bono legal clinic. As the Advisory Committee observed, the broad principle underlying Rule 47 of the PCR is that lawyers should not be permitted to unfairly attract paid work through pro bono work in legal clinics (see Illustrations 16 and 17). In one query, the issue was whether a lawyer who gave free legal advice to a pro bono client could refer that client to another member of the lawyer’s law practice to act in the same matter. The Advisory Committee opined that based on the broad principle, such an arrangement would be prohibited. However, as the scope of rule 47(3) of the PCR had yet to be decided by the Courts, the Advisory Committee opined that the lawyer would have to make a judgment call on this (see Illustration 16).

Client Confidentiality

In an age where data protection and cybersecurity concerns are paramount, a lawyer’s duty of client confidentiality takes on added importance. As a newly admitted lawyer who has just started working in a law practice environment, you may not be finely attuned to the need for client confidentiality. However, the duty of confidentiality is a strict one and there is no excuse for breaching it unless any of the exceptions in rule 6(3) of the PCR applies. Hence, you should be vigilant that you do not inadvertently disclose client confidences through causal lapses e.g. discussing your client’s case in public places or revealing a client’s confidential information to friends, significant others or perhaps even spouses.3See Alvin Chen, “Disclosing Client Confidences to Your Spouse or Significant Other” (Singapore Law Gazette, February 2019) <https://lawgazette.com.sg/practice/ethics-in-practice/disclosing-client-confidences-to-your-spouse-or-significant-other/>.

The Digest examines a different facet of client confidentiality regarding disclosure of a client’s confidential information to enforcement agencies for the purposes of their investigations (see Illustration 1). This is another common scenario that arises in practice and you should be mindful of the competing tensions to cooperate with enforcement agencies and to avoid breaching your duty of confidentiality to your client. In particular, the question whether you are “required by law” under rule 6(3)(b) of the PCR to disclose confidential information to the enforcement agency needs to be carefully considered.

Courtesy

Last but not least, courtesy and fairness between fellow practitioners is a long-standing tradition of the Bar. At all times, you should bear in mind the principles set out in rule 7(1) of the PCR, namely:

- Accord proper respect due to your fellow practitioner as a member of a noble and honourable profession;

- Deal with your fellow practitioner in good faith and in a manner which is dignified and courteous, so as to properly and satisfactorily conclude or resolve the matters in the best interests of your respective clients; and

- Not to deal with your fellow practitioner in any manner that may adversely affect the reputation and good standing of the legal profession or the practice of law in Singapore.

Illustration 2 in the Digest raises an interesting issue of whether a law practice currently acting for a party to legal proceedings may disclose to the Court the law practice’s correspondence with that party’s former practitioner. The Advisory Committee opined that rule 31 of the PCR, which deals with communications between practitioners currently acting for their respective clients in a matter, did not apply to the scenario presented. However, given the responsibility of a legal practitioner to treat another with “courtesy and fairness” under rule 7(2) of the PCR, the Advisory Committee opined that the consent of the party’s former practitioner should be sought before any such disclosure was made to the Court.

Conclusion

There are many other useful illustrations in the Digest which will help newly admitted lawyers resolve knotty ethical issues encountered in practice. But even based on the few illustrations from the Digest that are cited in this article, some useful take-aways are:

- Take an analytical approach in approaching your ethical obligations.

- Understand the broad principle underlying the ethical rule in question.

- Be mindful of competing tensions when construing your ethical obligations in the context of wider legal obligations.

- Where a specific ethical rule is not applicable to your scenario, consider whether there are other wider ethical obligations that you owe to the other party.

Ethical lawyering is therefore not a mechanical process of citing and applying a specific ethical rule, but requires a considered and informed analysis and application of the principles and obligations in the entire PCR. It is only when the external art of lawyering is aligned with its inner art that one can truly say that one is on the road to becoming a successful lawyer.

Endnotes

| ↑1 | Law Society of Singapore v Ezekiel Peter Latimer (2019) SGHC 92. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See rule 47(3)(a) of the PCR. |

| ↑3 | See Alvin Chen, “Disclosing Client Confidences to Your Spouse or Significant Other” (Singapore Law Gazette, February 2019) <https://lawgazette.com.sg/practice/ethics-in-practice/disclosing-client-confidences-to-your-spouse-or-significant-other/>. |