Law by Design: What the Legal Profession Can Learn from Design Thinking

In 2013, a group of designers, lawyers and technologists at Stanford University came together with the aim of developing innovative solutions to advance access to justice. They founded the Legal Design Lab (the Lab), based out of Stanford Law School’s Center on the Legal Profession and Stanford University’s Institute of Design, embodying a multidisciplinary and collaborative approach to experimenting in legal design and technology. The Lab aimed to conceptualise and create new legal products and services that were primarily user-centric. In doing so, users would be engaged, empowered, and better equipped to make more informed decisions about the products and services that they utilised within the context of the legal ecosystem.1Legal Design Lab, ‘About’ <http://www.legaltechdesign.com/about/> (accessed 13 October 2019).

Recognising that many members of the public found navigating the legal system and court processes to be intimidating, the Lab employed design thinking principles to identify the main challenges that these individuals were facing. One of the tools that was developed was “Wise Messenger”, a platform to set up automated text messages – including reminders and other procedural notifications – from a court or other legal organisation, to their users.2Justice Innovation – Stanford Legal Design Lab <http://justiceinnovation.law.stanford.edu/> (accessed 14 October 2019). See also Wise Messenger <https://wisemessenger.co/> (accessed 14 October 2019). The Lab invited litigants to participate in an ongoing research study on whether procedural notifications by text messages could help improve attendance rates at court hearings and other related appointments.3Ibid. The automated text messages would be sent to participants as part of a randomised control trial, with the Lab using the data to examine the impact of text reminders on attendance. This is just one of the many examples of the Lab’s efforts to utilise design thinking to make the legal system “more accessible, user-friendly and just”,4Ibid. and one that works better for people through engaging and effective solutions.

A Primer on Design Thinking

While the concept of design-thinking is not entirely new and has been regarded as natural and even intrinsic to the problem-solving process,5Rim Razzouk & Valerie Shute, “What is Design Thinking and Why Is It Important?” (2012) 82:3 Review of Educational Research 330 at 330, cited in Susan Ursel, “Building Better Law: How Design Thinking the term itself appeared to have gained prominence in our contemporary lexicon sometime in 2008, when the CEO of global design firm IDEO, Tim Brown, published his seminal article on the subject in the Harvard Business Review. Emphasising the “human-centred ethos” that lies at the core of design thinking, Tim Brown defined it as a discipline that “uses the designer’s sensibility and methods to match people’s needs with what is technologically feasible and what a viable business strategy can convert into customer value and market opportunity”.6Tim Brown, “Design Thinking” Harvard Business Review (June 2008) <https://new-ideo-com.s3.amazonaws.com/assets/files/pdfs/IDEO_HBR_DT_08.pdf> (accessed 30 September 2019).

Perhaps more famously, design thinking came to embody Apple’s approach to developing its product families and laid the foundations for Steve Jobs’ consumer-driven strategy and vision for the company.7Interestingly, Apple had commissioned IDEO in 1980 to develop Apple’s first usable mouse. The prototype was designed by IDEO’s founder, David Kelly, and his team. Kelly would go on to launch Stanford’s design school shortly after, and today, IDEO remains one of the most successful design and innovation firms in the world.

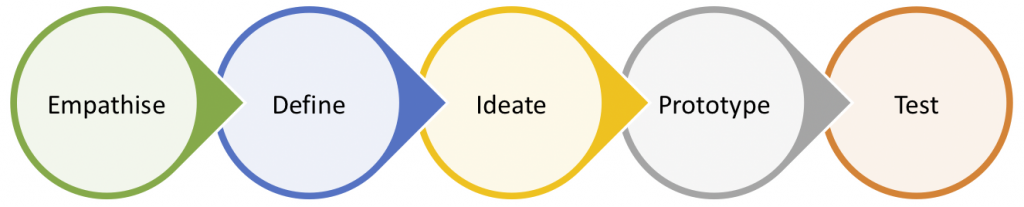

At its core, design thinking is a problem-solving approach. At the first stage of the design thinking process, innovators are tasked with identifying a problem or opportunity that motivates their search for solutions. This is also known as the “empathise” stage: innovators need to develop a sense of empathy towards their intended end-users by gaining insights into how they behave, feel and think, and why they demonstrate these particular behaviours, feelings and thoughts. Next, ideas for these possible solutions would need to be generated, developed and tested, bearing in mind business or resource constraints. This is done through numerous brainstorming sessions and is an ongoing process of refining existing ideas and even exploring new directions in the process. This leads to the creation of a prototype which needs to undergo rigorous testing across all the relevant stakeholder groups. At this stage, innovators should obtain and embrace feedback, and be open to restarting the design process and working on further refinements to the prototype.

After several rounds of refinements, the prototyped solution is ready to be implemented. However, the process does not end here – design thinking is a continuous, non-linear and ongoing process which requires innovators to constantly think of ways to improve the prototype even after implementation. This process has been described as the “perpetual loop of design thinking”,8Marshall Lichty, “Design Thinking for Lawyers” (18 October 2019) Lawyerist <https://lawyerist.com/blog/design-thinking-for-lawyers/> (20 October 2019). where there is a need to continually evaluate, learn, innovate and create to improve existing products and solutions.

Fig 1: A basic infographic depicting the key stages of the design thinking process

Beyond just a process, the principles of design thinking are applicable at multiple levels. For one, design thinking can be thought of as an organisational approach. Design thinking places an emphasis on innovating solutions that are desirable, feasible and viable.9Harvard University, “Designs on the law – The arrival of design thinking in the legal profession” (2019) 5:2 Adaptive Innovation <https://thepractice.law.harvard.edu/article/designs-on-the-law/> (accessed 15 October 2019). This ensures the solutions that are put forward – be it a product or service – are solutions that the consumer or end-user actually wants; a solution that is technically possible to develop and implement; and importantly, a solution that the organisation can afford to implement at a larger scale.

Finally, design thinking can also be regarded as a mindset. Design thinking places a strong emphasis on brainstorming and developing solutions with the end-user in mind and at the heart of the process. This governing ethos requires organisations that look to design thinking to cultivate a culture that encourages and supports the process and its “people-centric” nature. In this regard, empathy features strongly in the design thinking process. Innovators need to put aside their own assumptions and presuppositions and strive to better understand the needs, interests and frustrations of their end-users. It is only then that design thinking can achieve its aim of developing solutions that resonate and actually matter.

Clearly, design thinking has much to offer. But, how do the principles of design thinking apply to the law? Is it even possible to establish a nexus between the two, when the former places an emphasis on concepts such as empathy, ideation and experimentation, while the latter is often defined by strict procedures, expansive rules and regulations?10Ibid.

Embracing Design Thinking in the Legal Profession

A legal practitioner has to use, change and create legal ideas. Indeed, it has been suggested that the practice of law is akin to a design process, where lawyers are tasked with solving legal problems and designing solutions for their clients.11Susan Ursel, “Building Better Law: How Design Thinking Can Help Us Be Better Lawyers, Meet New Challenges, and Create the Future of Law” (2017) 34 Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice 28 at 58. One could even argue that the legal ecosystem is itself a highly designed system, or a series of systems, to facilitate various substantive and procedural aspects of the law. Susan Ursel, a senior partner with Canadian law firm Ursel Phillips Fellows Hopkinson, has advocated for lawyers and legal professionals to be more “deliberate” in engaging with the principles of design thinking in the practice of law.12Ibid. Ursel argues that law needs to be thought of as “a human designed and deliberate system of social organisation, in order to innovate”.13Ibid. See also Hague Institute for Innovation of Law (HiiL), “Why Do We Exist?” <http://www.hiil.org/about-us> (accessed 1 October 2019). However, it has been acknowledged that law, as a system, is not necessarily seen or practised as a creative process where design thinking would be a natural fit. As Mark Szabo, vice president of customer engagement agency Karo Group, observed:

“Lawyers are trained to understand a legal system, apply laws to specific sets of facts, and resolve the ambiguous space between the two. To accomplish this, they are trained to call upon past applications of law to facts, using legal precedent to guide the answer … the legal system places an extremely high value on reliability – the application of the past to determine a future course of action”.14Mark Szabo, “Design Thinking in Legal Practice Management” (2010) 21:3 Design Management Review 44.

Many would agree with Szabo’s assessment and at first blush, it would indeed appear to be the case that law would rather uneasily co-exist with the more free-flowing, indeterminate, and experimental nature of the design thinking process. Yet, design thinking may in fact build upon and play to the natural strengths of a lawyer or legal professional. At its core, design thinking is a solution-oriented process; lawyers, too, are problem-solvers and are called upon by clients to grapple with complex legal issues.

In fact, one can even argue that the design thinking process somewhat parallels the practice of law. Community lawyers, such as criminal law and family law practitioners, can uncover close similarities with the human-centredness that is inherent in the design thinking process; when emotions run high or an individual’s liberty or life is at stake, community lawyers must demonstrate empathy alongside grappling with the legal issues at play in a particular case. Civil or commercial lawyers would recognise the interdisciplinary nature of design thinking, where clients’ problems are often multi-faceted in nature and demand multiple sets of expertise and approaches from many angles of analysis. Inclusive solutions that would address the various dimensions of a legal problem may warrant not just legal inputs, but those of professionals in other relevant sectors, such as finance and accounting.

The practice of law today no longer functions in silos, and today’s lawyers need to consider and innovate solutions that often cannot be found within the bounds of case law and legal theory. It has even been observed that design thinking is no longer a “nice-to-have” for the legal profession, and that it increasingly features in various aspects of legal practice, such as legal drafting. Take for example the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): Articles 12, 13 and 14 mandate that privacy notices be drafted in clear and plain language that is easy to understand and accessible to the general public.15European Union, General Data Protection Regulation <https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679> (accessed 1 November 2019). These provisions arguably embody the core concept of design thinking that begins with the end-user in mind16Martijn Broersma, “Legal Design on a Blockchain” (2018) < https://medium.com/ltonetwork/legal-design-on-a-blockchain-845b89c40770> (accessed 1 November 2019). – in this case, members of the public who would be averse to technical, legal language. The process of drafting a privacy notice to satisfy the GDPR requirements is less a question of legal drafting; rather, it would likely require the application of design thinking principles to create a privacy notice that is accessible, concise and transparent.

Practical Applications of Design Thinking

Embracing design thinking in the legal profession is not a wildly radical concept. In fact, examples abound of law firms that have transformed and innovated through design thinking.

1. Trial advocacy

David Gross and Helen Chacon, litigators at Faegre Baker Daniels, a law firm based in Minnesota, championed design thinking as an offshoot of their ongoing work on trial strategy and visual advocacy. A chance meeting with the director of Stanford University’s Legal Design Lab, Margaret Hagen, introduced them to the world of design thinking for law.17Supra note 8. Gross and Chacon were invited to participate in a design sprint – a time-limited challenge where design thinking techniques are applied to solve a particular problem. The experience drove them to sign up for courses and training in design thinking – Gross even enrolled in a year-long programme at Stanford’s Design School while performing his day job as senior partner at the firm. They eventually developed a course on visual advocacy that is currently taught at the University of Minnesota Law School,18University of Minnesota Law School, ‘Visual Advocacy’ <https://www.law.umn.edu/course/6871/visual-advocacy> (accessed 28 October 2019). which equips students with strategies for visualising legal arguments and concepts to increase their persuasiveness as trial litigators.

2. Delivering legal services to clients

Other law firms have begun to embrace design thinking to re-design the delivery of legal services as well as enhance their firms’ value proposition to clients. In 2017, Baker McKenzie launched a new initiative, ‘Whitespace Legal Collab’.19‘Whitespace Legal Collab by Baker McKenzie’ <https://whitespacecollab.com/> (accessed 25 October 2019). With the aim of facilitating and encouraging multidisciplinary collaboration that would allow creative problem-solving to thrive, the initiative brought together academics, designers, executives, information technology experts and lawyers to prototype solutions at the interface of strategy, law and technology. Lawyers involved in the initiative through the various multidisciplinary and collaborative projects would also be able to develop capabilities to allow them to navigate increasingly complex, multijurisdictional and legal-related issues. The late Paul Rawlinson, former global chair of the firm, said that the initiative was part of the firm’s wider effort to “cultivate a new type of thinking when helping our clients develop solutions to complex challenges”.20Legal Business World, “Baker & McKenzie embraces Innovation: Whitespace Legal Collab Launch” (19 June 2017) <https://www.legalbusinessworld.com/single-post/2017/06/19/Baker-McKenzie-embraces-Innovation-Whitespace-Legal-Collab-Launch> (accessed 28 October 2019). The emphasis on collaboration and innovation would also enable the firm to harness technologies ranging from artificial intelligence to blockchain and quantum computing in developing solutions to address today’s multifaceted challenges. With clients becoming increasingly forward-looking and seeking solutions that are fit for their future, it is little wonder then that law firms today have to be proactive in cultivating new types of thinking to better serve their clients.

With an increasing emphasis being placed on enhancing legal service delivery, many law firms are looking to design thinking to gain deeper insight into their clients’ needs, and tailor their legal solutions accordingly. International law firm Seyfarth Shaw turned to design thinking to develop a new service model that would extend value to clients, and be accommodated and sustained within the firm’s existing business model.21The In-House Lawyer, “Back to the drawing board” (Winter 2018) <http://www.inhouselawyer.co.uk/mag-feature/back-to-the-drawing-board/> (accessed 1 November 2019). Recognising that while the costs of legal services was an important factor, it was not necessarily the determining factor for clients, who would also have other needs or interests that they would want addressed through the legal process. The firm created ‘client playbooks’, which mapped out individual clients’ needs, interests and touchpoints. This enabled the lawyers to better understand how to communicate more effectively with their respective clients and to package their solutions accordingly. Rather than viewing the lawyer-client relationship as a primarily transactional one, Seyfarth Shaw’s use of design thinking reframed the relationship as a journey – one that would not only be cost-effective, but also promote functional and technical value for their clients.22Ibid.

3. Improving firm’s internal processes

Beyond client engagement and improving legal service delivery, design thinking principles can also help a firm improve its own internal processes. A recent case study23Ibid. where design thinking was successfully applied within a law firm’s internal, organisational context was in the redesign of the associate review process at Hogan Lovells by IDEO. Associates at the firm were receiving their performance feedback on an irregular basis; this was compounded by the fact that the feedback received by the associates often lacked in specificity and substance, with little guidance provided on areas for improvement.24Katharine Schwab, Ideo redesigns the dreaded annual review” (29 May 2018), FastCompany <https://www.fastcompany.com/90173554/ideo-redesigns-the-dreaded-annual-review> (accessed 25 October 2019). Applying the principles of design thinking, IDEO first approached the associates to identify what they hoped to get from these performance reviews, and to provide their assessment of the gaps in the current performance feedback process. The next step in the process was to identify what Hogan Lovells sought to accomplish from its performance reviews and how managers and supervisors could also benefit from providing feedback to their associates.

The solution? Creating individual note cards with specific questions for each associate to facilitate 10-minute conversations between associates and their supervisors. The inclusion of targeted questions ensured that the feedback sessions were focused and more informal. This also allowed the associates to better engage with their supervisors. Through the application of design thinking principles, Hogan Lovells was able to re-think its internal processes pertaining to performance reviews and staff feedback, and facilitate more efficient talent development and employee engagement.

4. Design thinking for small and mid-sized firms

While these examples and case-studies involve larger law firms, this does not mean that design thinking is of limited utility to mid-size and smaller firms. Legal practice is also a business: whether a sole proprietor or leader of a mid-sized firm, they are similarly concerned with maintaining profit margins, optimising performance, as well as attracting and retaining new clients to sustain their businesses. Innovating and improving existing business strategies would also enable such firms to gain a competitive edge in the industry. Understandably, design thinking cannot be applied at a similar scale to that of the larger firms; however, design thinking does not demand a wealth of resources or even financial support to create impactful outcomes and solutions. As a simple example, a sole proprietor running a family law practice can apply design thinking principles to make his or her office setting less intimidating to clients. This can enhance the client experience and builds better lawyer-client relationships and client goodwill, which are undoubtedly valued by smaller firms.

The Future of Design Thinking in the Legal Profession

These examples demonstrate the many opportunities that design thinking represents for law. What does the future hold, then, for design thinking in the legal profession?

There is cause for optimism, as design thinking continues to gain momentum within the legal profession. From improving organisational processes and promoting efficient legal service delivery to enhancing access to justice, the process and principles of design thinking are arguably integral to the work of legal professionals. Today’s clients do not just demand legal knowledge from their lawyers; they are paying for legal services which require much more than knowledge. Likewise, today’s lawyers are not just selling their knowledge of the law; they are tasked with providing solutions that need to be forward-looking in their role as trusted advisors to their clients. Design thinking offers a framework that enables lawyers and law firms to place clients’ needs at the core, without losing sight of business considerations, as the examples above demonstrate.

Embracing design thinking thus requires a mindset shift for a legal professional; it necessitates rethinking processes and concepts to focus on the ‘users’ of legal services and the legal system as a whole. Importantly, design thinking cultivates a culture of innovation in the legal profession that not only benefits clients, but can also pave the way towards building better law for all stakeholders in the legal ecosystem.

Here is a selection of beginner-friendly resources to help you get started on design thinking:

Read

Brown, T. (2008). Design Thinking. Havard Business Review, (June 2008), 84–92.

The In-House Lawyer (2018). Back to the drawing board. Available at http://www.inhouselawyer.co.uk/mag-feature/back-to-the-drawing-board/

Allan, Craig. (2019). Design thinking – how to make it work for you. Law Society of Scotland, available at https://www.lawscot.org.uk/news-and-events/law-society-news/design-thinking-blog/

Kate Simpson (2017). Design thinking. Canadian Lawyer, available at https://www.canadianlawyermag.com/news/opinion/design-thinking/270476

Listen

The McKinsey Podcast: leading management consultancy McKinsey explores the application of design thinking in organisations

IDEO Futures: features interviews with guests from the creative and business industries

The Design of Business – The Business of Design: instructors Jessica Helfand and Michael Bierut from the Yale School of Management explores how design and business interface and intersect with one another

Learn

Introductory videos to design thinking

https://hbr.org/video/4443548301001/the-explainer-design-thinking

Selected free online courses on design thinking

Design Kit: The Course for Human-Centred Design (in collaboration with IDEO.org)

Design Thinking for Innovation (University of Virginia)

Inspirations for Design: A Course on Human-Centred Research (archived course by Hasso Plattner Institute, Potsdam University)

Endnotes

| ↑1 | Legal Design Lab, ‘About’ <http://www.legaltechdesign.com/about/> (accessed 13 October 2019). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Justice Innovation – Stanford Legal Design Lab <http://justiceinnovation.law.stanford.edu/> (accessed 14 October 2019). See also Wise Messenger <https://wisemessenger.co/> (accessed 14 October 2019). |

| ↑3 | Ibid. |

| ↑4 | Ibid. |

| ↑5 | Rim Razzouk & Valerie Shute, “What is Design Thinking and Why Is It Important?” (2012) 82:3 Review of Educational Research 330 at 330, cited in Susan Ursel, “Building Better Law: How Design Thinking |

| ↑6 | Tim Brown, “Design Thinking” Harvard Business Review (June 2008) <https://new-ideo-com.s3.amazonaws.com/assets/files/pdfs/IDEO_HBR_DT_08.pdf> (accessed 30 September 2019). |

| ↑7 | Interestingly, Apple had commissioned IDEO in 1980 to develop Apple’s first usable mouse. The prototype was designed by IDEO’s founder, David Kelly, and his team. Kelly would go on to launch Stanford’s design school shortly after, and today, IDEO remains one of the most successful design and innovation firms in the world. |

| ↑8 | Marshall Lichty, “Design Thinking for Lawyers” (18 October 2019) Lawyerist <https://lawyerist.com/blog/design-thinking-for-lawyers/> (20 October 2019). |

| ↑9 | Harvard University, “Designs on the law – The arrival of design thinking in the legal profession” (2019) 5:2 Adaptive Innovation <https://thepractice.law.harvard.edu/article/designs-on-the-law/> (accessed 15 October 2019). |

| ↑10 | Ibid. |

| ↑11 | Susan Ursel, “Building Better Law: How Design Thinking Can Help Us Be Better Lawyers, Meet New Challenges, and Create the Future of Law” (2017) 34 Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice 28 at 58. |

| ↑12 | Ibid. |

| ↑13 | Ibid. See also Hague Institute for Innovation of Law (HiiL), “Why Do We Exist?” <http://www.hiil.org/about-us> (accessed 1 October 2019). |

| ↑14 | Mark Szabo, “Design Thinking in Legal Practice Management” (2010) 21:3 Design Management Review 44. |

| ↑15 | European Union, General Data Protection Regulation <https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679> (accessed 1 November 2019). |

| ↑16 | Martijn Broersma, “Legal Design on a Blockchain” (2018) < https://medium.com/ltonetwork/legal-design-on-a-blockchain-845b89c40770> (accessed 1 November 2019). |

| ↑17 | Supra note 8. |

| ↑18 | University of Minnesota Law School, ‘Visual Advocacy’ <https://www.law.umn.edu/course/6871/visual-advocacy> (accessed 28 October 2019). |

| ↑19 | ‘Whitespace Legal Collab by Baker McKenzie’ <https://whitespacecollab.com/> (accessed 25 October 2019). |

| ↑20 | Legal Business World, “Baker & McKenzie embraces Innovation: Whitespace Legal Collab Launch” (19 June 2017) <https://www.legalbusinessworld.com/single-post/2017/06/19/Baker-McKenzie-embraces-Innovation-Whitespace-Legal-Collab-Launch> (accessed 28 October 2019). |

| ↑21 | The In-House Lawyer, “Back to the drawing board” (Winter 2018) <http://www.inhouselawyer.co.uk/mag-feature/back-to-the-drawing-board/> (accessed 1 November 2019). |

| ↑22 | Ibid. |

| ↑23 | Ibid. |

| ↑24 | Katharine Schwab, Ideo redesigns the dreaded annual review” (29 May 2018), FastCompany <https://www.fastcompany.com/90173554/ideo-redesigns-the-dreaded-annual-review> (accessed 25 October 2019). |