A Long Overdue Clarification of Wilful Blindness

Implications of Adili Chibuike Ejike and Gobi A/L Avedian

This article discusses the difficulty of the doctrine of wilful blindness and the welcome clarification in the Court of Appeal’s decision of Adili Chibuike Ejike and Gobi a/l Avedian. It highlights the key changes in the law resulting from the decision and the implications for the Prosecutor and Defence Counsel.

Introduction

This concept has long been fraught with difficulties and courts have sometimes conflated the concept of wilful blindness with the presumptions in sections 18(1) and (2) of the MDA. As an alternative to proving the fact of possession and knowledge or relying on the statutory presumptions, the Prosecution may also argue the accused’s wilful blindness as a basis for meeting the legal requirements of knowing possession and knowledge of the nature of the drugs.

It its simplest form, wilful blindness (also known as Nelsonian blindness)1Referring to Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson at the Battle of Copanhagen in 1801, who was said to have disobeyed his commander’s order to withdraw by holding his telescope to his blind eye to look at his commander’s signals – cited in Chan Wing Cheong, ‘Culpability in the Misuse of Drugs Act: Wilful Blindness, the Reasonable Person and a Duty to Check’ (2003) 25 Singapore Academy of Law Journal 110, Footnote 6. refers to the deliberate shutting of one’s eyes to an obvious situation.2Chan Wing Cheong, ‘Culpability in the Misuse of Drugs Act: Wilful Blindness, the Reasonable Person and a Duty to Check’ (2003) 25 Singapore Academy of Law Journal 110, 111. Essentially, if the accused had deliberately shut his/her eyes to knowledge of possession and knowledge of the nature of the drugs, the law can deem this as the equivalent of actual knowledge.

In Adili Chibuike Ejike and Gobi a/l Avedian, the Court of Appeal recently took the opportunity to clarify the issue. This has resulted in three notably implications:

- Wilful blindness refers to mental state short of actual knowledge but is taken to be its legal equivalent. The proof of an accused’s suspicions and a failure to enquire is no more than a means to show actual knowledge and should not be referred to as wilful blindness.

- Wilful blindness is distinct and separate from the presumption of knowledge in sections 18(1) and (2) of the MDA.

- The Prosecution may elect to rely on the presumption in section 18(1) or (2) of the MDA, or prove wilful blindness by making out the following three-part test:

| Wilful Blindness as to knowing possession | Wilful Blindness as to the knowledge of the nature of the drugs |

|---|---|

|

|

A Difficult Definition of Wilful Blindness

One reason for the confusion surrounding wilful blindness is the lack of a definition in the Penal Code. As illustrated below, judicial attempts to define wilful blindness have also led to some conflicting authority:

| Koo Pui Fong3Public Prosecutor v Koo Pui Fong (1996) 1 SLR(R) 734 (14). | This concept of wilful blindness does not introduce a new state of mind … it is simply a reformulation of actual knowledge … his wilful blindness being evidence from which knowledge may be inferred |

| Nagaenthran4Nagaenthran a/l K Dharmalingam v Public Prosecutor (2011) 4 SLR 1156 (30) | Wilful blindness is merely ”lawyer-speak” for actual knowledge that is inferred from the circumstances of the case. It seems to me that it is wholly in keeping with common sense and the law to say that an accused knew of certain facts if he deliberately closed his eyes to the circumstances, his wilful blindness being evidence from which knowledge may be inferred. |

| Tan Kiam Peng5Tan Kiam Peng v Public Prosecutor (2008) 1 SLR(R) 1 (129). | Wilful blindness cannot be equated with virtual certainty… as this would be to equate actual knowledge in its purest form … [it is] a combination of suspicion coupled with a deliberate decision not to make further inquiries |

| Mas Swan bin Adnan6Public Prosecutor v Mas Swan bin Adnan and another (2011) SGHC 107 (55). | Wilful blindness may be the legal equivalent of actual knowledge, but it is not the same as actual knowledge … [it is] an evidential tool towards establishing actual knowledge |

| Muhammad Ridzuan bin Md Ali7Muhammad Ridzuan bin Md Ali v Public Prosecutor and other matters (2014) 3 SLR 72 (76). | Wilful blindness refers to a person deliberately refusing to inquire into facts and from which an inference of knowledge may be sustained … Put simply, wilful blindness is the legal equivalent of actual knowledge. |

To compound this difficulty, there was some initial suggestion that wilful blindness could encompass negligence,8Dinesh Pillai a/l K Raja Retnam v Public Prosecutor (2012) 2 SLR 903. though this has since been resolved.9Tan Kiam Peng v Public Prosecutor (2008) 1 SLR(R) 1 (104)–(130). The difficulty around the concept of wilful blindness was also highlighted in the Penal Code Review Report, although the Review Committee took the view that the position had been reconciled in Nagaenthran.10Penal Code Review Committee, Penal Code Review Report (August 2018) 173-175, noting the pronouncements in Nagaenthran a/l K Dharmalingam v Public Prosecutor and another appeal (2019) 2 SLR 216 that s 18(2) of the MDA included both actual knowledge and wilful blindness, and that wilful blindness is merely ‘lawyer-speak’ for actual knowledge that is inferred from the circumstances. Notwithstanding the conflicting authorities, they appeared to suggest that wilful blindness could operate as either an evidential inference to prove actual knowledge or as the equivalent of actual knowledge.11See also Chan Wing Cheong, ‘Culpability in the Misuse of Drugs Act: Wilful Blindness, the Reasonable Person and a Duty to Check’ (2003) 25 Singapore Academy of Law Journal 110, 116 where the author suggests that wilful blindness is neither an independent fault element nor the legal equivalent of actual knowledge but an evidential matter to be considered in determining knowledge. Cf the ‘identity view’ stated in Toh Yung Cheong, ‘Knowing, Not Knowing and Almost Knowing: Knowledge and the Doctrine of Mens Rea’ (2008) 20 Singapore Academy of Law Review 680 (13).

Adili

This position is no longer the case since Adili, where the Court of Appeal clarified these concepts despite the fact that the issues were not raised by either party at trial. The accused was arrested in Singapore, having arrived there from Nigeria.12Adili Chibuike Ejike v Public Prosecutor (2019) 2 SLR 254. 1,961g of methamphetamine was found in the inner lining of his luggage, and he was charged with importation under section 7 of the MDA.

The trial proceeded on the basis that he was in possession of the luggage. This triggered the presumption under section 18(1) of the MDA that he was in possession of the drugs within the lining of the luggage. The Prosecution’s case was that he had not rebutted the presumption under section 18(1) of the MDA as he was wilfully blind. The Prosecution also relied on the presumption of knowledge under section 18(2) of the MDA.

The parties accepted that the accused was in possession of both the luggage and the drugs. The dispute centred around whether he knew the nature of the drugs. This required him to rebut the presumption under section 18(2) of the MDA on the balance of probabilities. The trial judge found the accused to be an unreliable witness due to inconsistencies in his version of events, and held that he had not rebutted the presumption under section 18(2) of the MDA. The accused was convicted.

The parties had accepted that the drugs were found in the accused’s luggage, and that the presumption under section 18(1) of the MDA applied to presume that he was in possession of the drugs in the luggage.13Public Prosecutor v Adili Chibuike Ejike (2017) SGHC 106 (3). The parties’ submissions and the trial judge’s findings focused primarily on the accused’s knowledge of the nature of the drug.14Public Prosecutor v Adili Chibuike Ejike (2017) SGHC 106 (23)–(41). Notwithstanding this, the Court of Appeal stated that the accused’s defence appeared to be that he was not even aware that the drugs were in the luggage. The focus should therefore be on section 18(1) of the MDA and knowing possession.15Adili Chibuike Ejike v Public Prosecutor (2019) 2 SLR 254 (29)–(30).

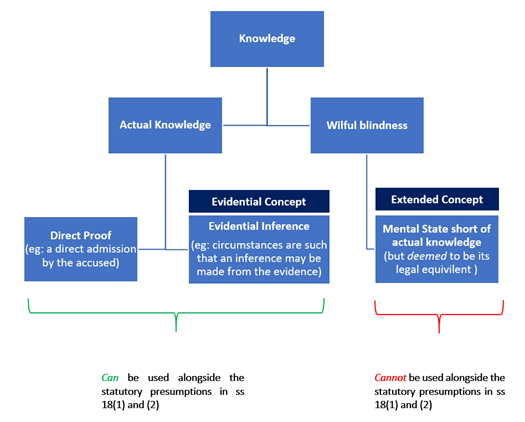

The Court of Appeal, recognising the confusion over the term ”wilful blindness”, took the opportunity to clarify the issue. The Court noted the term has been used in two distinct ways – the evidential sense and extended sense.16Adili Chibuike Ejike v Public Prosecutor (2019) 2 SLR 254 (45)–(47).

- The evidential sense of wilful blindness is no more than evidence to sustain a finding that the accused had actual knowledge based on his/her wilful blindness. The Court thus, based on the situation, infers that the accused had actual knowledge.17Similar to the ‘inference view’ stated in Toh Yung Cheong, ‘Knowing, Not Knowing and Almost Knowing: Knowledge and the Doctrine of Mens Rea’ (2008) 20 Singapore Academy of Law Review 680 (13). For avoidance of doubt, the Court of Appeal emphasised that that the term ”wilful blindness” should no longer be used to describe such a mental state.

- The extended sense of wilful blindness refers to a mental state that falls short of actual knowledge but is taken to be the legal equivalent of actual knowledge because of the circumstances.18Adili Chibuike Ejike v Public Prosecutor (2019) 2 SLR 254 (47). The Court stated that the phrase ”wilful blindness” should, going forward, only be used to describe this scenario.

The Court clarified that to make out wilful blindness, the following elements need to be made out by the Prosecution:19Adili Chibuike Ejike v Public Prosecutor (2019) 2 SLR 254 (51).

- The accused person must have had a clear, grounded and targeted suspicion of the fact to which he is said to have been wilfully blind;

- There must have been reasonable means of inquiry available to the accused person, which, if taken, would have led him to discovery of the truth, at least in the context of the fact of possession; and

- The accused person must have deliberately refused to pursue the reasonable means of inquiry available so as to avoid such negative legal consequences as might arise in connection with his knowing that fact.

A summary of these concepts is set out below:

| Evidential Concept | Extended Concept | |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Where the accused’s suspicion and failure to enquire is used as evidence to infer that the accused had actual knowledge | Where the accused’s mental state may fall short of actual knowledge, but the law inputs the legal equivalent of actual knowledge if the three elements indicated above are made out |

| Comments | Should not be referred to as wilful blindness

Is only evidential inference of actual knowledge |

Is wilful blindness as it falls short of actual knowledge but the law imputes this as the equivalent of actual knowledge |

This clarification is timely given the constant confusion over the issue. While it would have been useful to have wilful blindness itself defined in the Code, the Penal Code Review Committee declined to do so in 2018, stating that its determination is a fact sensitive exercise that requires flexibility.20Penal Code Review Committee, Penal Code Review Report (August 2018) (43). Indeed, in the Statutes (Miscellaneous Amendments) Bill, the newly inserted definition of ‘knowing’ under section 26D of the Penal Code was specifically amended to preserve the position set out in Adili, which the original draft of section 26D would have abolished. As articulated by Senior Minister of State for Law, Edwin Tong, this was to ensure ”further development of the doctrine of wilful blindness by the common law”.21Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Official Report (1 June 2020) vol 2 (Edwin Tong Chun Fai, Senior Minister of State for Law).

The Court of Appeal’s decision in Adili can therefore be taken to be the latest authoritative position on the issue, and as will be analysed in the following sections, there are implications of this redefined concept of wilful blindness interact with the statutory presumptions under sections 18(1) and (2) of the MDA. However, critical to the outcome in Adili is the second element of ”wilful blindness”, which requires that there must have been reasonable means of inquiry available to the accused person, which, if taken, would have led him to discovery of the truth. While Adili’s case applies this in the context of knowing possession, whether Adili had knowledge that the drugs were inside the luggage, the following sections analyse this along with knowledge of the nature of the drug and the applications of the respective statutory presumptions.

Implications of Adili

Wilful Blindness and Possession

The Court of Appeal held that the Prosecution had failed to prove that the accused was wilfully blind as to his knowledge that he was in possession of the drugs within the luggage. Central to this was the Court’s finding that because the drugs were carefully hidden within the lining of the accused’s luggage, there were no means of inquiry available to the accused.22Adili Chibuike Ejike v Public Prosecutor (2019) 2 SLR 254 (84)–(91). This element of a reasonable means of inquiry being available to the accused will pose an additional burden on the Prosecution in proving its case.

Drug syndicates involved in the international drug trade are unlikely to place the drugs in a manner allowing for them to be easily discovered by the accused (or for that matter, law enforcement officers). Common methods of concealment include hiding the drugs within sealed cans of food,23Obeng Comfort v Public Prosecutor (2017) 1 SLR 633 (3). inside electronic devices,24Obeng Comfort v Public Prosecutor (2017) 1 SLR 633 (3). and behind car panels.25Public Prosecutor v Mohd Zaini Bin Zainutdin and others (2019) SGHC (6). In all such cases, the means of inquiry would not have been readily open to the drug courier.

The issue of whether an accused can be said to be wilfully blind should turn on his/her subjective state of mind at the material time and whether or not his/her inquiry would lead to the truth. It is suggested that the availability of a reasonable means of inquiry should not be a requirement to make out wilful blindness. The Court of Appeal’s decision on this has been criticised by some, with the suggestion for a modification to the three-part test.26See the concerns raised by Member of Parliament Christopher de Souza in Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Official Report (8 July 2019) vol 94 at col 4 (Christopher de Sousa, Member for Holland-Bukit Timah); Rennie Whang, ‘The Doctrine of Wilful Blindness in Drug Offences’ (2020) 32 Singapore Academy of Law Journal 305 (20).

Wilful Blindness and the Presumption of Possession

Adili is also significant in terms of the interaction between wilful blindness and the statutory presumption of knowledge under s 18(1) of the MDA. The section reads as follows:

Presumption of possession and knowledge of controlled drugs

18.—(1) Any person who is proved to have had in his possession or custody or under his control —

[Emphasis added]

The Court of Appeal held that the phrase ”who is proved” requires proof of actual knowledge of the existence of the drug, note merely wilful blindness. This is because wilful blindness falls short of actual knowledge even though it is imputed as its legal equivalent. The Court emphasised that wilful blindness is thus irrelevant to whether the section 18(1) presumption is rebutted.27Adili Chibuike Ejike v Public Prosecutor (2019) 2 SLR 254 (71).

In short, section 18(1) of the MDA may only be relied on where prosecutors adduce proof of actual knowledge but not through the doctrine of wilful blindness. This article finds no fault with this concept and agrees that based on the bifurcation of actual knowledge and wilful blindness, a plain reading of section 18(1) of the MDA suggests that proof of the former is required.

Wilful Blindness and Knowledge of the Nature of the Drugs

While Adili was only concerned with section 18(1), the subsequent decision of Gobi has extended this concept to section 18(2). In Gobi, the Court of Appeal took the unusual step in hearing a concluded case under section 394J of the Criminal Procedure Code to determine if the new legal interpretation of wilful blindness arising from Adili would have implications for Gobi, whose appeal the Court of Appeal had already dismissed in 2019.

The Court of Appeal held that the wilful blindness and section 18(2) of the MDA were distinct concepts. As the Prosecution’s case against Gobi at trial was that the accused was wilfully blind as to the nature of the drugs in his possession, they could not then also rely on the presumption in section 18(2) of the Misuse of Drugs Act.28Gobi a/l Avedian v Public Prosecutor (2020) SGCA 102 (49). Given the conflation of these two concepts prior to Adili¸ the Prosecution has not properly put its case of wilful blindness to the accused at trial and an acquittal was justified on this basis.29Gobi a/l Avedian v Public Prosecutor (2020) SGCA 102 (119)-(120).

As a result of Adili and Gobi, wilful blindness is a separate and distinct concept from section 18(2) of the MDA. Prosecutors who seek to make out wilful blindness (whether in respect of possession or knowledge) must make out the three-part test (as summarised in the introduction to this article) beyond reasonable doubt.

Conclusion

Adili has clarified that wilful blindness a mental state that falls short of actual knowledge but the law imputes this as the equivalent of actual knowledge. This is wilful knowledge in the extended sense. An accused’s suspicion and a failure to enquire used to infer that the accused had actual knowledge has previously also been referred to as wilful blindness (albeit in the evidential sense) but should no longer be termed as such.

Given Adili and Gobi, wilful blindness is also now irrelevant as far as sections 18(1) and (2) of the MDA is concerned. Prosecutors may elect to prove wilful blindness as an alternative to relying on sections 18(1) or (2) of the MDA but need to make out the three-part test, including showing that the accused had a reasonable means of inquiry available to the accused person, which, if taken, would have led him to discovery of the truth.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and not representative of any institutions he may be affiliated with.

Endnotes

| ↑1 | Referring to Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson at the Battle of Copanhagen in 1801, who was said to have disobeyed his commander’s order to withdraw by holding his telescope to his blind eye to look at his commander’s signals – cited in Chan Wing Cheong, ‘Culpability in the Misuse of Drugs Act: Wilful Blindness, the Reasonable Person and a Duty to Check’ (2003) 25 Singapore Academy of Law Journal 110, Footnote 6. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Chan Wing Cheong, ‘Culpability in the Misuse of Drugs Act: Wilful Blindness, the Reasonable Person and a Duty to Check’ (2003) 25 Singapore Academy of Law Journal 110, 111. |

| ↑3 | Public Prosecutor v Koo Pui Fong (1996) 1 SLR(R) 734 (14). |

| ↑4 | Nagaenthran a/l K Dharmalingam v Public Prosecutor (2011) 4 SLR 1156 (30) |

| ↑5 | Tan Kiam Peng v Public Prosecutor (2008) 1 SLR(R) 1 (129). |

| ↑6 | Public Prosecutor v Mas Swan bin Adnan and another (2011) SGHC 107 (55). |

| ↑7 | Muhammad Ridzuan bin Md Ali v Public Prosecutor and other matters (2014) 3 SLR 72 (76). |

| ↑8 | Dinesh Pillai a/l K Raja Retnam v Public Prosecutor (2012) 2 SLR 903. |

| ↑9 | Tan Kiam Peng v Public Prosecutor (2008) 1 SLR(R) 1 (104)–(130). |

| ↑10 | Penal Code Review Committee, Penal Code Review Report (August 2018) 173-175, noting the pronouncements in Nagaenthran a/l K Dharmalingam v Public Prosecutor and another appeal (2019) 2 SLR 216 that s 18(2) of the MDA included both actual knowledge and wilful blindness, and that wilful blindness is merely ‘lawyer-speak’ for actual knowledge that is inferred from the circumstances. |

| ↑11 | See also Chan Wing Cheong, ‘Culpability in the Misuse of Drugs Act: Wilful Blindness, the Reasonable Person and a Duty to Check’ (2003) 25 Singapore Academy of Law Journal 110, 116 where the author suggests that wilful blindness is neither an independent fault element nor the legal equivalent of actual knowledge but an evidential matter to be considered in determining knowledge. Cf the ‘identity view’ stated in Toh Yung Cheong, ‘Knowing, Not Knowing and Almost Knowing: Knowledge and the Doctrine of Mens Rea’ (2008) 20 Singapore Academy of Law Review 680 (13). |

| ↑12 | Adili Chibuike Ejike v Public Prosecutor (2019) 2 SLR 254. |

| ↑13 | Public Prosecutor v Adili Chibuike Ejike (2017) SGHC 106 (3). |

| ↑14 | Public Prosecutor v Adili Chibuike Ejike (2017) SGHC 106 (23)–(41). |

| ↑15 | Adili Chibuike Ejike v Public Prosecutor (2019) 2 SLR 254 (29)–(30). |

| ↑16 | Adili Chibuike Ejike v Public Prosecutor (2019) 2 SLR 254 (45)–(47). |

| ↑17 | Similar to the ‘inference view’ stated in Toh Yung Cheong, ‘Knowing, Not Knowing and Almost Knowing: Knowledge and the Doctrine of Mens Rea’ (2008) 20 Singapore Academy of Law Review 680 (13). |

| ↑18 | Adili Chibuike Ejike v Public Prosecutor (2019) 2 SLR 254 (47). |

| ↑19 | Adili Chibuike Ejike v Public Prosecutor (2019) 2 SLR 254 (51). |

| ↑20 | Penal Code Review Committee, Penal Code Review Report (August 2018) (43). |

| ↑21 | Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Official Report (1 June 2020) vol 2 (Edwin Tong Chun Fai, Senior Minister of State for Law). |

| ↑22 | Adili Chibuike Ejike v Public Prosecutor (2019) 2 SLR 254 (84)–(91). |

| ↑23 | Obeng Comfort v Public Prosecutor (2017) 1 SLR 633 (3). |

| ↑24 | Obeng Comfort v Public Prosecutor (2017) 1 SLR 633 (3). |

| ↑25 | Public Prosecutor v Mohd Zaini Bin Zainutdin and others (2019) SGHC (6). |

| ↑26 | See the concerns raised by Member of Parliament Christopher de Souza in Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Official Report (8 July 2019) vol 94 at col 4 (Christopher de Sousa, Member for Holland-Bukit Timah); Rennie Whang, ‘The Doctrine of Wilful Blindness in Drug Offences’ (2020) 32 Singapore Academy of Law Journal 305 (20). |

| ↑27 | Adili Chibuike Ejike v Public Prosecutor (2019) 2 SLR 254 (71). |

| ↑28 | Gobi a/l Avedian v Public Prosecutor (2020) SGCA 102 (49). |

| ↑29 | Gobi a/l Avedian v Public Prosecutor (2020) SGCA 102 (119)-(120). |