Perhaps It is Time to Consider a Spandeck Approach to Developing Sentencing Frameworks

Since the formation of the Sentencing Council in March 2013, the number of sentencing guideline judgments have proliferated.

There are six common sentencing approaches:

- “five-step sentencing bands” approach;

- “two-step sentencing bands” approach;

- “sentencing matrix” approach;

- “multiple starting points” approach;

- “benchmark” approach; and

- “single starting point” approach.

The author submits that a “Spandeck” should be done, whereby the 2nd to 6th approaches should be unified under the “five-step sentencing bands” approach which should be the single sentencing approach hereon to develop the sentencing framework of any offence.

This article will explore the six sentencing approaches.

Since the formation of the Sentencing Council in March 2013,1See (2) of The Honourable Justice Chao Hick Tin, “The Art of Sentencing – An Appellate Court’s Perspective”, at the Sentencing Conference 2014: Trends, Tools & Technology (“CHT Speech 2014”). the number of sentencing guideline judgments2In this article, the term “sentencing guideline judgment” refers to a sentencing judgment which “provides the focal point against which sentences in subsequent cases, with differing degrees of criminal culpability, can be accurately determined… (and) therefore lays down carefully the parameters of its reasoning in order to allow future judges to determine what falls within the scope of the “norm”, and what exceptional situations justify departure from it.”: per Abu Syeed Chowdhury v Public Prosecutor (2002) 1 SLR(R) 182 (SGHC) (“Abu Syeed Chowdhury”) at (15); see also S Chandra Mohan and Tan Yock Lin, Criminal Procedure in Singapore and Malaysia (LexisNexis, Looseleaf Ed, 2012, 2019 release) (“TYL Looseleaf”) at (802) on pp. XVII 251 – 252. issued by the Singapore Courts have proliferated.3See Benny Tan Zhi Peng, “Assessing the Effectiveness of Sentencing Guideline Judgments in Singapore issued post-March 2013 and a Guide to Constructing Frameworks” (2018) 30 SAcLJ 1004 (16 October 2018) (“Benny Tan 2018”), at Appendix A where the learned authored identified at least 55 sentencing guideline judgments issued from March 2013 to March 2018; see also Kow Keng Siong, Sentencing Principles in Singapore (Law Practice Series) (SAL Academy Publishing, Second Edition, 2019) at (13.054) – (13.056) on pp. 427 to 437, where the learned authored set out 11 pages of case list of sentencing guidelines judgments. Also, in 2018, the Attorney-General heralded a shift in prosecution’s submissions by placing more weight on sentencing principles than precedents: see (25) of Speech by Attorney-General, Mr Lucien Wong, S.C., at the Opening of Legal Year 2018 (“AG Speech 2018”).

There are at least4There are also other approaches, albeit less common, such as the points-based multi-variable approach in Lim Teck Kim v PP (2019) 5 SLR 279 (SGHC), and the Contour Matrix approach in Takaaki Masui v PP and another appeal and other matters (2020) SGHC 265 (“Takaaki Masui”) at (262) – (283). six common sentencing approaches5The 2nd to 6th approaches were explained in Ng Kean Meng Terence v PP (2007) 2 SLR 449 (SGCA) at (26) – (34) and (39), whereas the 1st approach was used in Logachev Vladislav v PP (2018) 4 SLR 609 (SGHC). For an analysis and critique on these approaches, refer to Benny Tan 2018 at 1060 to 1063.:

- “five-step sentencing bands” approach;

- “two-step sentencing bands” approach;

- “sentencing matrix” approach;

- “multiple starting points” approach;

- “benchmark” approach; and

- “single starting point” approach.

The author submits that the 2nd to 6th approaches should be unified under 1st approach, i.e. the “five-step sentencing bands” approach, which should be the single sentencing approach hereon to develop the appropriate sentencing framework6This article differentiates between a “sentencing approach” and a “sentencing framework”. The former is the methodology to derive the latter. The latter is the sentencing guideline for Courts to apply to the case at hand. In other words, different sentencing frameworks may emanate from a single sentencing approach; cf the terminology used in Takaaki Masui at (102) – (103). of any given offence (assuming that offence is suitable for a sentencing framework to be developed7For the factors on when a sentencing guideline judgment is appropriate to be issued for a particular offence, see: Mohamed Faizal, Wong Woon Kwong and Sarah Shi, Criminal Procedure, Evidence and Sentencing (2018) 19 SAL Ann Rev 411 (16 July 2019) at (14.62); Huang Ying-Chun v PP (2019) 3 SLR 606 (SGHC) at (32) – (34); Ye Lin Myint v PP (2019) 5 SLR 1005 (SGHC) at (42); Takaaki Masui at (90), (91) and (93); PP v Wong Chee Meng and another appeal (2020) 5 SLR 807 (SGHC) at (51) and (55); Suventher Shanmugam v PP (2017) 2 SLR 115 (SGCA) at (4); PP v Tan Kok Ming Michael and other appeals (2019) 5 SLR 926 (SGHC); Edwin s/o Suse Nathen v PP (2013) 4 SLR 1139 (SGHC) at (1) and (31); Chiew Kok Chai v PP (2019) 5 SLR 713 (SGHC) at (28) and (31); Abu Syeed Chowdhury at (16) and (24).).

In this regard, a leaf may be taken from Spandeck8Spandeck Engineering (S) Pte Ltd v Defence Science & Technology Agency (2007) 4 SLR(R) 100 (SGCA). where the Court of Appeal took the bold and admirable step to unify and set out a single test to determine the imposition of a duty of care for all negligence claims, irrespective of the type of damages. This provided clarity and consistency to the law, and eliminated the perception that there were two or more applicable tests. Such clarity and consistency is also desirable in criminal sentencing.

Each sentencing approaches will be explained below, along with how the other five approaches may be integrated within the “five-step sentencing bands” approach or how they are deficient in comparison.9This is an extract of the author’s submissions as amicus curiae in HC/MA 9758/2020.

1. The “Five-step Sentencing Bands” Approach

The “five-step sentencing bands” approach was developed in Logachev10Logachev Vladislav v PP (2018) 4 SLR 609 (SGHC) (“Logachev”) at (76) – (84). which involves the offence of cheating at play under section 172A Casino Control Act.

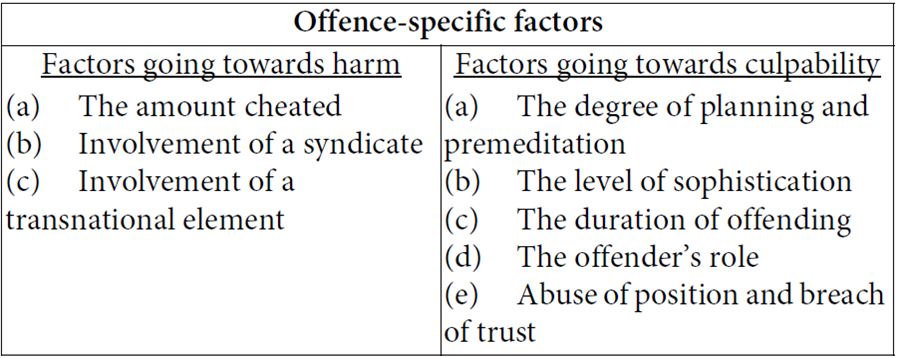

First step: Identify all the offence-specific factors and categorise them into different baskets. The categorization would usually be into the twin baskets of “harm” and “culpability” because these are the two principal parameters generally used to evaluate the seriousness of a crime.11See Logachev at (35): “In PP v Koh Thiam Huat (2017) 4 SLR 1099…, the High Court held (at (41)) that the two principal parameters which a sentencing court would generally have regard to in evaluating the seriousness of a crime were: (a) the harm caused by the offence; and (b) the offender’s culpability. Harm was a measure of the injury caused to society by the commission of the offence, while culpability was a measure of the degree of relative blameworthiness disclosed by the offender’s actions and was assessed chiefly in relation to the extent and manner of the offender’s involvement in the criminal act…” However, the author would not foreclose the possibility of other baskets given the wide range of criminal offences.See also (25) of the AG Speech 2018: “My officers have studied the issue and we will move towards placing more weight on sentencing principles than precedents when deriving the sentencing positions which we submit to the Court. The key focus is to anchor our sentencing positions based on the level of culpability and harm, which is then adjusted for any aggravating and mitigating factors.”

For example, in Logachev12See (37). the offence-specific factors were:

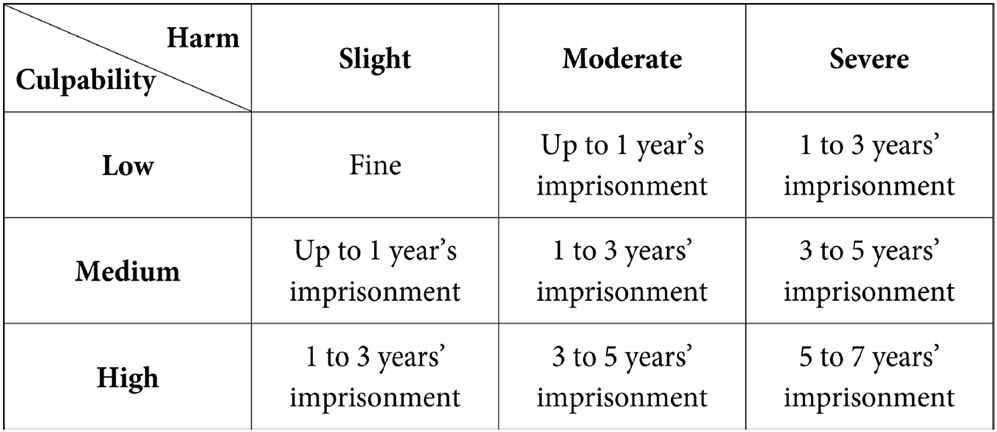

Second step: Split the full sentencing range prescribed in the provision, into various sentencing bands based on the baskets of offence-specific factors, bearing in mind sentencing precedents and parliamentary intention.

For example, in Logachev,13See (78). the sentencing bands were:

Thereafter, identify which particular band the case at hand broadly falls within, based on the offence-specific factors present in the case, to arrive at the indicative sentencing range. If possible, the author suggests that the Court should provide examples of the paradigm factors for each threshold of “harm” or “culpability”.14For example, the UK Sentencing Council’s Guideline for Revenue Fraud: https://www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk/offences/magistrates-court/item/revenue-fraud/

Third step: Granulate the case at hand into the indicative sentencing range, by identifying the appropriate starting point within the identified sentencing band based on the same offence-specific factors present in the case at hand but now applied with a finer weighing of these factors. This process may be aided by sentencing precedents and a consideration of which of these offence-specific factors are aggravating or mitigating factors.

Fourth step: Apply any adjustments to the identified starting point by considering offender-specific factors present in the case, which may be aggravating and/or mitigating factors. This results in the individual sentence for each offence.

For example, in Logachev,15See (37). the offender-specific factors were:

Fifth step: For multiple offences, consider the totality principle for any adjustments to aggregate sentence.16Logachev at (81) – (84). The author suggests enhancing this step by replacing it with the analytical framework in Shouffee17Mohamed Shouffee bin Adam v PP (2014) 2 SLR 998 (SGHC) at (81). which considers the totality principle and one-transaction rule.

2. The “Two-step Sentencing Bands” Approach

This approach was explained in Terence Ng18Ng Kean Meng Terence v PP (2007) 2 SLR 449 (SGCA) (“Terrence Ng”) at (39). as follows:

“First, the court should identify under which band the offence in question falls within, having regard to the factors which relate to the manner and mode by which the offence was committed as well as the harm caused to the victim (we shall refer to these as “offence-specific” factors). Once the sentencing band, which defines the range of sentences which may usually be imposed for a case with those offence-specific features, has been identified the court should then determine precisely where within that range the present offence falls in order to derive an “indicative starting point”, which reflects the intrinsic seriousness of the offending act.

Secondly, the court should have regard to the aggravating and mitigating factors which are personal to the offender to calibrate the appropriate sentence for that offender. These “offender-specific” factors relate to the offender’s particular personal circumstances and, by definition, cannot be the factors which have already been taken into account in the categorisation of the offence. In exceptional circumstances, the court is entitled to move outside of the prescribed range for that band if, in its view, the case warrants such a departure.”

The first step of the “two-step sentencing bands” approach is the same as the first three steps of the “five-step sentencing bands” approach, that is, using offence-specific factors to determine the indicative sentencing bands for the case at hand.

The second step of the “two-step sentencing bands” approach is the same as the fourth step of the “five-step sentencing bands” approach, that is, to apply the offender-specific factors to adjust the sentence within the indicative sentencing band.

If the offender is convicted of multiple offences, the fifth step of the “five-step sentencing bands” would also need to be applied after the “two-step sentencing bands” approach.

Hence, there is no practical difference between the two approaches.

3. The “Sentencing Matrix” Approach

This approach was explained in Terence Ng19See (33). as follows:

“The court first begins by considering the seriousness of an offence by reference to the “principal factual elements” of the case in order to give the case a preliminary classification (in practice, this is done by locating the position of the case in a sentencing matrix, with each cell in the matrix featuring a different indicative starting point and sentencing range …)”

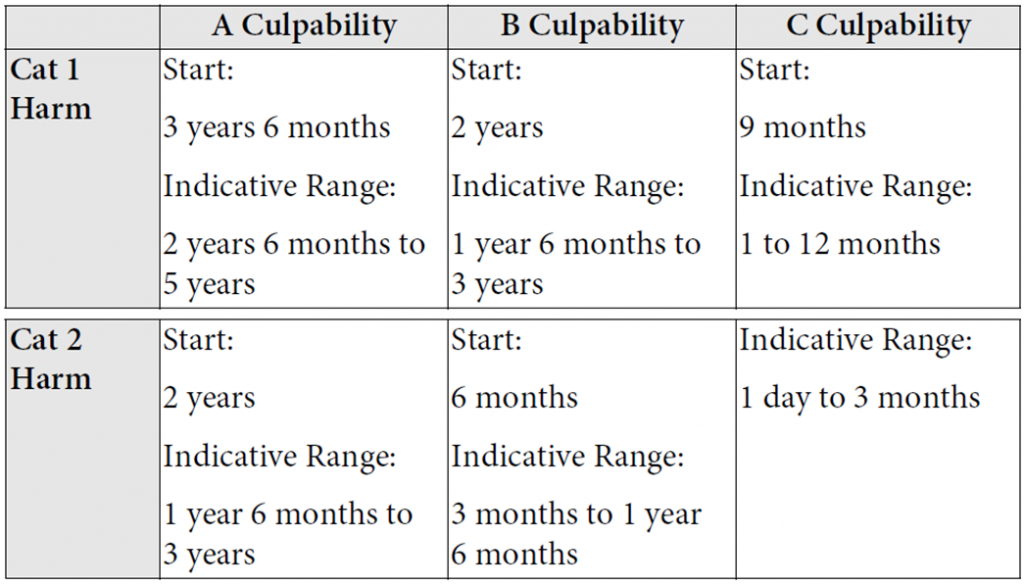

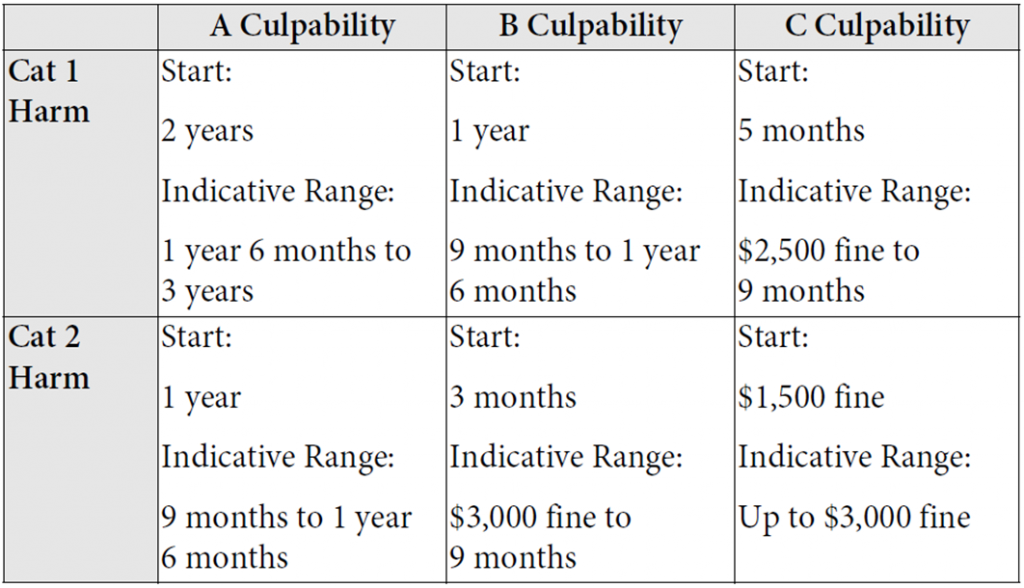

For example, in Poh Boon Kiat,20Poh Boon Kiat v PP (2014) 4 SLR 892 (SGHC) (“Poh Boon Kiat”) at (75) – (78). involving offences under the Women’s Charter, the sentencing matrices were:

Sections 140(1)(b), 140(1)(d) and 146

Sections 147 and 148

The above sentencing matrices are essentially the first two steps of the “five-step sentencing bands” approach, and they also employed the two baskets of “harm” and “culpability” factors.

In Terence Ng, the Court opined that the “two-step sentencing bands” approach (same as the “five-step sentencing bands” approach) distinguishes between offence-specific factors and offender-specific factors, whereas this is absent in the “sentencing matrix” approach.21See (37). However, the author highlights that in Poh Boon Kiat22See (79), the Court held that the sentencing matrices are only indicative starting points and the precise sentence is dependent on the circumstances by assessing “where in the range of circumstances constituting A, B or C Culpability and Category 1 or 2 harm the precise facts fall as well as any aggravating or mitigating circumstances which might be present in each individual case.” 23See (79). This essentially is the third and fourth steps of the “five-step sentencing bands” approach.

In Terence Ng, the Court also opined that the “sentencing matrix” approach examines only the “principal factual elements” of the offence, unlike the “two-step sentencing bands” approach which looks at “all” offence-specific factors.24See (37). However, the author respectfully differs.

Firstly, there is no meaningful difference in outcome between an approach that considers the “principal factual elements” versus one that considers all offence-specific factors. The latter approach is given effect by ultimately distilling “all” factors to their broader “principal factual elements”. Hence, it is difficult to identify any missing offence-specific factors in the “principal factual elements” identified in Poh Boon Kiat25See (74) to (76). which would have materially affected the sentencing matrices. Moreover, even under the “five-step sentencing bands” approach, the Courts have acknowledged that the offence-specific factors are not exhaustive.26See Logachev at (38) and (74).

Secondly, any difference is minimal, otherwise the “principal factual elements” approach is defective to begin with because it had failed to consider significant offence-specific factors.

Thirdly, any difference is ameliorated by the third step of the “five-step sentencing bands” approach which applies any non-principal elements to adjust the starting point within the identified sentencing range.

Hence, the “sentencing matrix” approach is substantively same as the “five-step sentencing bands” approach. The striking similarities perhaps explain why some learned authors have viewed case authorities applying the “sentencing matrix” approach to be also using the “two-step sentencing bands” approach.27For example, in Ho Hsi Ming, Shawn, “Analytical Framework for Sentencing: Harm, Culpability and Aggravating/Mitigating Factors”, Law Gazette (January 2019) (“DJ Shawn’s Article”), the learned District Judge had identified the Poh Boon Kiat and Koh Yong Chiah v PP (2017) 3 SLR 447 (SGHC) (“Koh Yong Chiah”) as falling within the “eclectic mix of cases” employing the “two-step sentencing bands” approach (which the author approximates to the “five-step sentencing bands” approach), even though Terence Ng at (33) had identified both cases as applying the “sentencing matrix” approach.

4. The “Multiple Starting Points” Approach

This approach was explained in Terence Ng28See (29). as follows:

“The multiple starting points approach involves the setting of different indicative starting points, each corresponding to a different class of the offence. Once an indicative starting point has been established by reference to the classification of the offence, it will then be adjusted in the conventional way (that is to say, by having regard to the aggravating and mitigating factors in the case)…”

For example, in Vasentha,29Vasentha d/o Joseph v PP (2015) 5 SLR 122 (SGHC) (“Vasentha”) at (47). which involve the offence of trafficking diamorphine, the sentencing framework was:

The above are indicative starting points which may be adjusted based on the offender’s culpability, and any aggravating and mitigating factors, which examples include30See (48), (51), (54) and (70).:

| Culpability | Indicia |

|---|---|

| Higher |

|

| Lower |

|

Aggravating Factors

|

Mitigating Factors

|

The Vasentha approach is similar to the “five-step sentencing bands” approach. The weight of diamorphine represents the “harm”. The above tables are a mixture of the “culpability” offence-specific factors, and the offender-specific aggravating and mitigating factors.31See also passages in (23), (34) and (42).

Although the “culpability” offence-specific factors were relegated to “adjustment” factors (to be applied after identifying the applicable sentencing band) instead of being featured directly in the sentencing bands, this is to give primacy to parliamentary intention.32See Opening Address by the Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon at the Sentencing Conference 2014 (9 October 2014) (“CJ Speech 2014”) at (8) – (9); see also Mehra Radhika v Public Prosecutor (2015) 1 SLR 96 (SGHC) at (27) – (28) which was followed in Chan Chun Hong v Public Prosecutor (2016) 3 SLR 465 (SGHC) at (37). Parliament intended sentences to be primarily determined by the weight of drug as evidenced by the sentencing structure in the Second Schedule and parliamentary debates.33The relevant portions of the parliamentary debates were reviewed in Vasentha at (14) and (18). As Parliament ascribed great importance to the weight of drug, this basket is given immediate effect first, by using it to formulate the sentencing bands in the second step, whereas the other offence-specific factors are used in the third step to determine the appropriate starting point within the indicative sentencing band. Hence, it is not invariably that the sentencing bands must comprise a table of two or more baskets of offence-specific factors where there is good reason for one basket to take primacy over the other(s).34See also Takaaki Masui at (127) – (133) where the Court observed that the “sentencing framework” approach (which is the equivalent of the “five-step sentencing bands” approach used in these submissions) may take the form of a single independent variable, or double variable, or multi-variable, depending on whether “there is more than one dominant or principal determinant of the indicative sentence”.

Accordingly, the “multiple starting points” approach contains the same substantive elements as the “five-step sentencing bands”. Again, the striking similarities perhaps explain why some learned authors have viewed these two approaches to be the same.35For example, in the DJ Shawn’s Article, the learned District Judge had identified Vasentha as “(o)ne model of the two-step sentencing bands framework” , even though the Court in Terence Ng at (29) had identified Vasentha as using the “multiple starting points” approach.

5. The “Benchmark” Approach

This approach was explained in Terence Ng36See (31). as follows:

“The benchmark approach calls for the identification of an archetypal case (or a series of archetypal cases) and the sentence which should be imposed in respect of such a case. This notional case must be defined with some specificity, both in terms of the factual matrix of the case in question as well as the sentencing considerations which inform the sentence that is meted out, in order that future courts can use it as a touchstone…”

For example, in Wong Hoi Len,37Wong Hoi Len v PP (2009) 1 SLR(R) 115 (SGHC) (“Wong Hoi Len”) at (20). the Court held that:

“… where an accused person with no antecedent pleads guilty to a charge under s 323 of the Penal Code [for voluntarily causing hurt] and the recipient of violence is a public transport worker, I am of the view that the starting benchmark for a simple assault should be a custodial sentence of around four weeks. The actual sentence meted out would, however, be dependent on the peculiar circumstances of each incident … . Careful attention must be given to the precise factual matrices …”

The above is a problematic sentencing framework.

Firstly, it myopically fixates on a seemingly “archetypal case” which does not address other archetypes. The benchmark caters to public transport workers, but what if the victims are public servants or other vulnerable persons – should the Court start afresh in sentencing, or apply an uplift or discount to the above benchmark and what are the calibration metrics?

Secondly, the one-off benchmark sentence is arbitrary. It does not show how the Court arrived at the four weeks, and how should the remaining 23 months sentencing range be applied.

Thirdly, the benchmark sentence of four weeks’ imprisonment is without upper limit, which does not assist in sentencing for variants of the same archetype. For example, where the attack on the public transport worker was due to provocation, or the public transport worker was in a vulnerable position or age, or the attack caused the vehicle to swerve dangerously. How should the sentence be calibrated from this benchmark of four weeks?

See [20] to [26], [44] and [49]. The above problems are avoided in the “five-step sentencing bands” approach. The Court in Wong Hoi Len38See (20) to (26), (44) and (49). had already identified various offence-specific and offender-specific factors, which can then be applied to the “five-step sentencing bands” approach to derive a sentencing framework that can house the benchmark of four weeks.

6. The “Single Starting Point” Approach

This approach was explained in Terence Ng39See (27) and (28). as follows:

“… this calls for the identification of a notional starting point which will then be adjusted taking into account the aggravating and mitigating factors in the case…”

For example, in Frederick Chia40Chia Kim Heng Frederick v Public Prosecutor (1992) 1 SLR(R) 63 (SGCA) (“Frederick Chia”) at (20), albeit this sentencing guideline was subsequently no longer followed: see Terence Ng at (28). (Frederick Chia), the Court held as follows:

“… for a rape committed without any aggravating or mitigating factors, a figure of ten years’ imprisonment should be taken as the starting point in a contested case, in addition to caning. The court should then consider in turn the mitigating factors which merit a reduction of the sentence… and whether there were other factors… which justify a longer sentence.”

The above single starting point of 10 years’ imprisonment, without any calibration of the full sentencing range prescribed, is similar to the benchmark sentence of minimum four weeks in Wong Hoi Len. As one learned commentator has noted,41Benny Tan 2018 at 1060. the “benchmark” approach is strictly not a standalone sentencing approach, and overlaps with the other sentencing approaches, especially the “single starting point” approach:

“For a start, the benchmark approach is in fact not truly a standalone approach. A benchmark sentence, as it is commonly understood, is simply a presumptive sentence for an archetypal case or a series of archetypal cases, defined based on a stipulated set of factual matrix for an offence. Seen in this light, the benchmark approach is simply the genus approach, under which the other four main approaches are species or subsets:

- The single starting point approach is simply a benchmark approach that sets a presumptive sentence without first considering any factual elements of the case…”

Therefore, the “single starting point” approach suffers the same deficiencies as the “benchmark” approach, and it is perhaps even more deficient as there is consistently no sentencing upper limit (unlike some42There are cases setting benchmark sentences with an upper limit, for example in PP v Fernando Payagala Waduge Malitha Kumar (2007) 2 SLR(R) 334 (SGHC) at (75) (identified in Terence Ng at (32)), for Section 420 Penal Code credit card cheating offences, where the Court issued benchmark sentences of 24 to 36 months for syndicated and/or counterfeit/forged credit card and/or sophisticated offences, and 12 to 18 months for sophisticated offences non-syndicated stolen/misappropriated credit card offences. Yet, even then, this is only one sentencing band which do not fully cover the full sentencing range prescribed as “imprisonment of a term which may extend to 7 years, and shall also be liable to fine”. Hence, it suffers the same deficiencies. benchmark sentences).

7. Benefits of the “Five-step Sentencing Bands” Approach Being the Single Approach for Developing Sentencing Frameworks

In Takaaki Masui,43Takaaki Masui v PP and another appeal and other matters (2020) SGHC 265 (“Takaaki Masui”) at (3). the Court opined that: “When constructing frameworks and guidelines, the form that each framework or guideline takes is secondary. What matters is its substantive content, and whether it adheres to and abides by the broad general principles of sentencing.”

The substance of the “five-step sentencing bands” approach is the most comprehensive, structured and principled, and it can cover most (if not all) offences. Using it as the single approach for developing sentencing frameworks would achieve all the goals44The goals of sentencing frameworks were expressed in the following authorities:(1) CHT Speech 2014 at (12): “… The principal benefits of guideline judgements, according to Ashworth (Ashworth, “Techniques of Guidance on Sentencing” (1984) Crim LR 519 at 521.), are that firstly, it forces the appellate court to consider interrelationships of sentences between the different forms of an offence. Secondly, instead of having to deal with a series of potentially conflicting appellate decisions, sentencers in the lower courts are given a specific framework to operate within. And finally, guidance is found in one judgment rather than a number of disparate sources…”(2) Terence Ng at (23): “As argued in Saul Holt, “Appellate Sentencing Guidance in New Zealand” 3 NZPGLEJ 1…, a good guideline sentencing judgment should strive to (at 38): (a) ensure consistency in sentencing; (b) maintain an appropriate level of flexibility and discretion for sentencing courts; (c) encourage transparency in reasoning; and (d) create a “coherent picture of sentencing for a particular offence” – that is to say, it must respect the statutory context by taking into account the whole range of penalties prescribed, including the mandatory minimum punishments set out in the relevant statute.”(3) Pang Shuo at (28): “A good sentencing framework thus provides the analytical frame of reference to allow the sentencing judge to achieve a reasoned, fair and appropriate sentence in line with other like cases while having due regard to the facts of each particular case. Such guidelines also promote public confidence in sentencing, and enhance sentencing transparency and accountability in the administration of criminal justice. Broad consistency in sentencing also provides society with a clear understanding of what and how the law seeks to punish and allows for members of society to have regard to this in arranging their own affairs and making their own choices (see Menon CJ’s extra-judicial comments during his opening address at the Sentencing Conference 2014 at (17)…”(4) Benny Tan 2018 at 1016 at (20): “(a) promote consistency in sentencing yet maintain an appropriate level of flexibility and discretion for sentencing judges; (b) encourage transparency in reasoning; and (c) create a coherent picture of sentencing for a particular offence, which presumably would include ensuring rationality and avoiding arbitrariness in sentencing.”(5) Takaaki Masui at (121), citing Terence Ng at (23) and Benny Tan 2018 at (20); see also Takaaki Masui at (94): “I believe that a prescribed sentencing framework will help sentencing courts to achieve a broadly consistent sentencing outcome. First, it will help the court to understand where a particular offender falls within the spectrum of the severity of offending. Second, it will enable the court, prosecutors and defence counsel to weed out precedent cases with sentencing outcomes that are wildly inconsistent with the general trend of similar cases. Third, it will cause sentencing courts to apply the same broad methodology, barring exceptional circumstances.” of a good sentencing framework.

Firstly, a single sentencing approach reduces confusion or dilemma for sentencing courts to consider which of the six approaches ought to be applied to develop a sentencing framework for the case at hand. The judges need not re-invent the wheel and can follow the five steps.

Secondly, the step-by-step and principled approach forces the judges to consider the full sentencing range prescribed and to express their reasoning in arriving at a particular sentence,45There is a judicial duty to give reasons when sentencing, especially for criminal cases where personal liberties are affected: see CJ Speech 2014 at (20) – (23) which mitigates the perceived arbitrariness of arriving at a magic number. This allows their judgments to withstand greater scrutiny and increase public understanding of the sentencing thought process, thereby engendering greater public confidence in the administration of criminal justice.46Importance of public confidence in sentencing and administration of criminal justice, see the following:(1) CHT Speech 2014 at (7): “As pertinently observed by Lord Bingham CJ in R v Howells (R v Howells (1999) 1 All ER 50 at (54)) that there is a public dimension to sentencing: “Courts should always bear in mind that criminal sentences are in almost every case intended to protect the public, whether by punishing the offender or reforming him and others, or all of these things. Courts cannot and should not be unmindful of the important public dimension of criminal sentencing and the importance of maintaining public confidence in the sentencing system”.”(2) Pang Shuo at (28): “A good sentencing framework thus provides the analytical frame of reference to allow the sentencing judge to achieve a reasoned, fair and appropriate sentence in line with other like cases while having due regard to the facts of each particular case. Such guidelines also promote public confidence in sentencing, and enhance sentencing transparency and accountability in the administration of criminal justice. Broad consistency in sentencing also provides society with a clear understanding of what and how the law seeks to punish and allows for members of society to have regard to this in arranging their own affairs and making their own choices (see Menon CJ’s extra-judicial comments during his opening address at the Sentencing Conference 2014 at (17)…”(3) AG Speech 2018 at (25): “…a key initiative which AGC will be undertaking this year in the administration of criminal justice, touching on the topic of sentencing positions. I understand the public disquiet and frustration when egregious conduct is not, to the public’s mind, adequately punished. My officers have studied the issue and we will move towards placing more weight on sentencing principles than precedents when deriving the sentencing positions which we submit to the Court. The key focus is to anchor our sentencing positions based on the level of culpability and harm, which is then adjusted for any aggravating and mitigating factors. In doing so, we will give full consideration to the range of sentencing options provided for under the law, to ensure sentencing parity and proportionality. We will work towards implementing this throughout the course of the year. The public should rest assured that we will continue to refine our approach towards criminal justice, with the view to ensuring that no misconduct goes unpunished, that all misconduct is justly punished, and that all persons are equally treated before the law.”(4) TYL Looseleaf at (703) – (800).

Thirdly, when the sentencing frameworks begin to speak the same currency (by adopting the same sentencing approach), it allows easier and more principled comparisons between sentencing frameworks for variants of the same offence (e.g. first-time offender or repeat offender of the same offence47See for example, PP v Lai Teck Guan (2018) 5 SLR 852 (SGHC) at (37) and (42) where the Court found that the Vasentha sentencing bands for first-time offenders of trafficking diamorphine was not suitable for repeated offences by way of applying a mathematical uplift, but nonetheless found the Vasentha sentencing bands useful for an indicative uplift which the Court used to then create new sentencing bands for repeated offenders.), or for different offences but similar in nature or criminality48See for example, Ghazali bin Mohamed Rasul v PP (2014) 4 SLR 57 (SGHC) at (50) where the Court compared the sentences of offences of similar criminality. (e.g. trafficking different types of drugs,49See for example, Loo Pei Xiang Alan v PP (2015) 5 SLR 500 (SGHC) at (17) where the Court found it possible to derive a “conversion scale” or “exchange rate” between trafficking diamorphine and trafficking methamphetamine for sentencing. or trafficking drugs versus importing drugs50See for example, K Saravanan Kuppusamy v PP (2016) 5 SLR 88 (SGHC) at (4) where the Court appreciated the nuanced differences between the structure of the prescribed punishments for importation versus trafficking under MDA but decided to proceed without distinction in their sentences because they have the same overall tenor.). This facilitates an incremental approach51See CHT Speech 2014 at (14); for the importance of incremental approach to sentencing see for example PP v Tan Kok Ming Michael and other appeals (2019) 5 SLR 926 (SGHC) at (104) where the Court declined to develop a sentencing framework, and instead, at (105) the Court drew upon existing case precedents to apply to the case at hand: “In line with the many sentencing precedents, I would adopt the approach of articulating, developing and clarifying the categories and factors for consideration by sentencing courts.”; Liew Zheng Yang v PP (2017) 5 SLR 1160 (SGHC) at (9) – (12) where the Court declined to develop a sentencing framework, and at (16) adopted the incremental approach: “Therefore I would approach the sentencing of this case in the usual way by examining the aggravating and mitigating factors which are germane to the charge of possession for the purpose of his own consumption, keeping in mind the existing sentencing precedents”; Takaaki Masui at (78); YL Looseleaf at (804) on p XVII 253 – 254 and (805) on p XVII 255 – 256. to developing new sentencing frameworks for other situations or offences. For example, the identified offence-specific and offender-specific factors of one sentencing framework may be extended to others.

8. Conclusion

It has been said that the Courts are still in the experimental, exploratory and discovery phase of finding the best way to structure sentencing discretion and issuing sentencing guidelines.52See Benny Tan 2018 at 1047 at (74). This may explain why the six sentencing approaches have overlapping features without bright line differentiation53See Benny Tan 2018 at 1060 at (1); see also DJ Shawn’s Article, where the article had identified Poh Boon Kiat and Koh Yong Chiah and Vasentha as falling within the “two-step sentencing bands” approach even though Terence Ng had identified those cases as falling under other approaches. and that the “five-step sentencing bands” approach arguably encompasses the best parts of the other sentencing approaches, which may be visualized as follows:

The Courts have been exploring the various sentencing approaches over the years, on a needs-basis as and when the cases gradually percolate54CHT Speech 2014 at (14). up to the appellate courts. The sentencing approaches are gradually being fine-tuned and culminating55This perhaps explains why the Court of Appeal’s general observation of sentencing approaches in (133) of PP v ASR (2019) 1 SLR 941 (SGCA) below, is quintessentially congruent with the substantive technique or spirit of the “five-step sentencing bands” approach: “Part of the reason why retribution may be “displaced” in this way is because it is hard to say with absolute quantitative precision what an offender deserves for his crime. That is why, where a sentencing framework is in play, the general practice is that the court first identifies the appropriate sentencing range on the basis of the harm caused and the offender’s culpability, and then, having regard to other sentencing factors, including outcome-focused sentencing objectives, chooses the appropriate sentence within that range. The range operates as a margin of reasonableness which ensures that the eventual sentence imposed remains broadly proportionate to the crime…” in the present “five-step sentencing bands” approach which is now much more refined and comprehensive enough to cover most (if not all) offences that are appropriate for a sentencing framework.

Therefore, it may be time for a “Spandeck”, to adopt the “five-step sentencing bands” approach as the single approach for developing sentencing frameworks hereon.

Endnotes

| ↑1 | See (2) of The Honourable Justice Chao Hick Tin, “The Art of Sentencing – An Appellate Court’s Perspective”, at the Sentencing Conference 2014: Trends, Tools & Technology (“CHT Speech 2014”). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | In this article, the term “sentencing guideline judgment” refers to a sentencing judgment which “provides the focal point against which sentences in subsequent cases, with differing degrees of criminal culpability, can be accurately determined… (and) therefore lays down carefully the parameters of its reasoning in order to allow future judges to determine what falls within the scope of the “norm”, and what exceptional situations justify departure from it.”: per Abu Syeed Chowdhury v Public Prosecutor (2002) 1 SLR(R) 182 (SGHC) (“Abu Syeed Chowdhury”) at (15); see also S Chandra Mohan and Tan Yock Lin, Criminal Procedure in Singapore and Malaysia (LexisNexis, Looseleaf Ed, 2012, 2019 release) (“TYL Looseleaf”) at (802) on pp. XVII 251 – 252. |

| ↑3 | See Benny Tan Zhi Peng, “Assessing the Effectiveness of Sentencing Guideline Judgments in Singapore issued post-March 2013 and a Guide to Constructing Frameworks” (2018) 30 SAcLJ 1004 (16 October 2018) (“Benny Tan 2018”), at Appendix A where the learned authored identified at least 55 sentencing guideline judgments issued from March 2013 to March 2018; see also Kow Keng Siong, Sentencing Principles in Singapore (Law Practice Series) (SAL Academy Publishing, Second Edition, 2019) at (13.054) – (13.056) on pp. 427 to 437, where the learned authored set out 11 pages of case list of sentencing guidelines judgments. Also, in 2018, the Attorney-General heralded a shift in prosecution’s submissions by placing more weight on sentencing principles than precedents: see (25) of Speech by Attorney-General, Mr Lucien Wong, S.C., at the Opening of Legal Year 2018 (“AG Speech 2018”). |

| ↑4 | There are also other approaches, albeit less common, such as the points-based multi-variable approach in Lim Teck Kim v PP (2019) 5 SLR 279 (SGHC), and the Contour Matrix approach in Takaaki Masui v PP and another appeal and other matters (2020) SGHC 265 (“Takaaki Masui”) at (262) – (283). |

| ↑5 | The 2nd to 6th approaches were explained in Ng Kean Meng Terence v PP (2007) 2 SLR 449 (SGCA) at (26) – (34) and (39), whereas the 1st approach was used in Logachev Vladislav v PP (2018) 4 SLR 609 (SGHC). For an analysis and critique on these approaches, refer to Benny Tan 2018 at 1060 to 1063. |

| ↑6 | This article differentiates between a “sentencing approach” and a “sentencing framework”. The former is the methodology to derive the latter. The latter is the sentencing guideline for Courts to apply to the case at hand. In other words, different sentencing frameworks may emanate from a single sentencing approach; cf the terminology used in Takaaki Masui at (102) – (103). |

| ↑7 | For the factors on when a sentencing guideline judgment is appropriate to be issued for a particular offence, see: Mohamed Faizal, Wong Woon Kwong and Sarah Shi, Criminal Procedure, Evidence and Sentencing (2018) 19 SAL Ann Rev 411 (16 July 2019) at (14.62); Huang Ying-Chun v PP (2019) 3 SLR 606 (SGHC) at (32) – (34); Ye Lin Myint v PP (2019) 5 SLR 1005 (SGHC) at (42); Takaaki Masui at (90), (91) and (93); PP v Wong Chee Meng and another appeal (2020) 5 SLR 807 (SGHC) at (51) and (55); Suventher Shanmugam v PP (2017) 2 SLR 115 (SGCA) at (4); PP v Tan Kok Ming Michael and other appeals (2019) 5 SLR 926 (SGHC); Edwin s/o Suse Nathen v PP (2013) 4 SLR 1139 (SGHC) at (1) and (31); Chiew Kok Chai v PP (2019) 5 SLR 713 (SGHC) at (28) and (31); Abu Syeed Chowdhury at (16) and (24). |

| ↑8 | Spandeck Engineering (S) Pte Ltd v Defence Science & Technology Agency (2007) 4 SLR(R) 100 (SGCA). |

| ↑9 | This is an extract of the author’s submissions as amicus curiae in HC/MA 9758/2020. |

| ↑10 | Logachev Vladislav v PP (2018) 4 SLR 609 (SGHC) (“Logachev”) at (76) – (84). |

| ↑11 | See Logachev at (35): “In PP v Koh Thiam Huat (2017) 4 SLR 1099…, the High Court held (at (41)) that the two principal parameters which a sentencing court would generally have regard to in evaluating the seriousness of a crime were: (a) the harm caused by the offence; and (b) the offender’s culpability. Harm was a measure of the injury caused to society by the commission of the offence, while culpability was a measure of the degree of relative blameworthiness disclosed by the offender’s actions and was assessed chiefly in relation to the extent and manner of the offender’s involvement in the criminal act…” However, the author would not foreclose the possibility of other baskets given the wide range of criminal offences.See also (25) of the AG Speech 2018: “My officers have studied the issue and we will move towards placing more weight on sentencing principles than precedents when deriving the sentencing positions which we submit to the Court. The key focus is to anchor our sentencing positions based on the level of culpability and harm, which is then adjusted for any aggravating and mitigating factors.” |

| ↑12 | See (37). |

| ↑13 | See (78). |

| ↑14 | For example, the UK Sentencing Council’s Guideline for Revenue Fraud: https://www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk/offences/magistrates-court/item/revenue-fraud/ |

| ↑15 | See (37). |

| ↑16 | Logachev at (81) – (84). |

| ↑17 | Mohamed Shouffee bin Adam v PP (2014) 2 SLR 998 (SGHC) at (81). |

| ↑18 | Ng Kean Meng Terence v PP (2007) 2 SLR 449 (SGCA) (“Terrence Ng”) at (39). |

| ↑19 | See (33). |

| ↑20 | Poh Boon Kiat v PP (2014) 4 SLR 892 (SGHC) (“Poh Boon Kiat”) at (75) – (78). |

| ↑21 | See (37). |

| ↑22 | See (79) |

| ↑23 | See (79). |

| ↑24 | See (37). |

| ↑25 | See (74) to (76). |

| ↑26 | See Logachev at (38) and (74). |

| ↑27 | For example, in Ho Hsi Ming, Shawn, “Analytical Framework for Sentencing: Harm, Culpability and Aggravating/Mitigating Factors”, Law Gazette (January 2019) (“DJ Shawn’s Article”), the learned District Judge had identified the Poh Boon Kiat and Koh Yong Chiah v PP (2017) 3 SLR 447 (SGHC) (“Koh Yong Chiah”) as falling within the “eclectic mix of cases” employing the “two-step sentencing bands” approach (which the author approximates to the “five-step sentencing bands” approach), even though Terence Ng at (33) had identified both cases as applying the “sentencing matrix” approach. |

| ↑28 | See (29). |

| ↑29 | Vasentha d/o Joseph v PP (2015) 5 SLR 122 (SGHC) (“Vasentha”) at (47). |

| ↑30 | See (48), (51), (54) and (70). |

| ↑31 | See also passages in (23), (34) and (42). |

| ↑32 | See Opening Address by the Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon at the Sentencing Conference 2014 (9 October 2014) (“CJ Speech 2014”) at (8) – (9); see also Mehra Radhika v Public Prosecutor (2015) 1 SLR 96 (SGHC) at (27) – (28) which was followed in Chan Chun Hong v Public Prosecutor (2016) 3 SLR 465 (SGHC) at (37). |

| ↑33 | The relevant portions of the parliamentary debates were reviewed in Vasentha at (14) and (18). |

| ↑34 | See also Takaaki Masui at (127) – (133) where the Court observed that the “sentencing framework” approach (which is the equivalent of the “five-step sentencing bands” approach used in these submissions) may take the form of a single independent variable, or double variable, or multi-variable, depending on whether “there is more than one dominant or principal determinant of the indicative sentence”. |

| ↑35 | For example, in the DJ Shawn’s Article, the learned District Judge had identified Vasentha as “(o)ne model of the two-step sentencing bands framework” , even though the Court in Terence Ng at (29) had identified Vasentha as using the “multiple starting points” approach. |

| ↑36 | See (31). |

| ↑37 | Wong Hoi Len v PP (2009) 1 SLR(R) 115 (SGHC) (“Wong Hoi Len”) at (20). |

| ↑38 | See (20) to (26), (44) and (49). |

| ↑39 | See (27) and (28). |

| ↑40 | Chia Kim Heng Frederick v Public Prosecutor (1992) 1 SLR(R) 63 (SGCA) (“Frederick Chia”) at (20), albeit this sentencing guideline was subsequently no longer followed: see Terence Ng at (28). |

| ↑41 | Benny Tan 2018 at 1060. |

| ↑42 | There are cases setting benchmark sentences with an upper limit, for example in PP v Fernando Payagala Waduge Malitha Kumar (2007) 2 SLR(R) 334 (SGHC) at (75) (identified in Terence Ng at (32)), for Section 420 Penal Code credit card cheating offences, where the Court issued benchmark sentences of 24 to 36 months for syndicated and/or counterfeit/forged credit card and/or sophisticated offences, and 12 to 18 months for sophisticated offences non-syndicated stolen/misappropriated credit card offences. Yet, even then, this is only one sentencing band which do not fully cover the full sentencing range prescribed as “imprisonment of a term which may extend to 7 years, and shall also be liable to fine”. Hence, it suffers the same deficiencies. |

| ↑43 | Takaaki Masui v PP and another appeal and other matters (2020) SGHC 265 (“Takaaki Masui”) at (3). |

| ↑44 | The goals of sentencing frameworks were expressed in the following authorities:(1) CHT Speech 2014 at (12): “… The principal benefits of guideline judgements, according to Ashworth (Ashworth, “Techniques of Guidance on Sentencing” (1984) Crim LR 519 at 521.), are that firstly, it forces the appellate court to consider interrelationships of sentences between the different forms of an offence. Secondly, instead of having to deal with a series of potentially conflicting appellate decisions, sentencers in the lower courts are given a specific framework to operate within. And finally, guidance is found in one judgment rather than a number of disparate sources…”(2) Terence Ng at (23): “As argued in Saul Holt, “Appellate Sentencing Guidance in New Zealand” 3 NZPGLEJ 1…, a good guideline sentencing judgment should strive to (at 38): (a) ensure consistency in sentencing; (b) maintain an appropriate level of flexibility and discretion for sentencing courts; (c) encourage transparency in reasoning; and (d) create a “coherent picture of sentencing for a particular offence” – that is to say, it must respect the statutory context by taking into account the whole range of penalties prescribed, including the mandatory minimum punishments set out in the relevant statute.”(3) Pang Shuo at (28): “A good sentencing framework thus provides the analytical frame of reference to allow the sentencing judge to achieve a reasoned, fair and appropriate sentence in line with other like cases while having due regard to the facts of each particular case. Such guidelines also promote public confidence in sentencing, and enhance sentencing transparency and accountability in the administration of criminal justice. Broad consistency in sentencing also provides society with a clear understanding of what and how the law seeks to punish and allows for members of society to have regard to this in arranging their own affairs and making their own choices (see Menon CJ’s extra-judicial comments during his opening address at the Sentencing Conference 2014 at (17)…”(4) Benny Tan 2018 at 1016 at (20): “(a) promote consistency in sentencing yet maintain an appropriate level of flexibility and discretion for sentencing judges; (b) encourage transparency in reasoning; and (c) create a coherent picture of sentencing for a particular offence, which presumably would include ensuring rationality and avoiding arbitrariness in sentencing.”(5) Takaaki Masui at (121), citing Terence Ng at (23) and Benny Tan 2018 at (20); see also Takaaki Masui at (94): “I believe that a prescribed sentencing framework will help sentencing courts to achieve a broadly consistent sentencing outcome. First, it will help the court to understand where a particular offender falls within the spectrum of the severity of offending. Second, it will enable the court, prosecutors and defence counsel to weed out precedent cases with sentencing outcomes that are wildly inconsistent with the general trend of similar cases. Third, it will cause sentencing courts to apply the same broad methodology, barring exceptional circumstances.” |

| ↑45 | There is a judicial duty to give reasons when sentencing, especially for criminal cases where personal liberties are affected: see CJ Speech 2014 at (20) – (23) |

| ↑46 | Importance of public confidence in sentencing and administration of criminal justice, see the following:(1) CHT Speech 2014 at (7): “As pertinently observed by Lord Bingham CJ in R v Howells (R v Howells (1999) 1 All ER 50 at (54)) that there is a public dimension to sentencing: “Courts should always bear in mind that criminal sentences are in almost every case intended to protect the public, whether by punishing the offender or reforming him and others, or all of these things. Courts cannot and should not be unmindful of the important public dimension of criminal sentencing and the importance of maintaining public confidence in the sentencing system”.”(2) Pang Shuo at (28): “A good sentencing framework thus provides the analytical frame of reference to allow the sentencing judge to achieve a reasoned, fair and appropriate sentence in line with other like cases while having due regard to the facts of each particular case. Such guidelines also promote public confidence in sentencing, and enhance sentencing transparency and accountability in the administration of criminal justice. Broad consistency in sentencing also provides society with a clear understanding of what and how the law seeks to punish and allows for members of society to have regard to this in arranging their own affairs and making their own choices (see Menon CJ’s extra-judicial comments during his opening address at the Sentencing Conference 2014 at (17)…”(3) AG Speech 2018 at (25): “…a key initiative which AGC will be undertaking this year in the administration of criminal justice, touching on the topic of sentencing positions. I understand the public disquiet and frustration when egregious conduct is not, to the public’s mind, adequately punished. My officers have studied the issue and we will move towards placing more weight on sentencing principles than precedents when deriving the sentencing positions which we submit to the Court. The key focus is to anchor our sentencing positions based on the level of culpability and harm, which is then adjusted for any aggravating and mitigating factors. In doing so, we will give full consideration to the range of sentencing options provided for under the law, to ensure sentencing parity and proportionality. We will work towards implementing this throughout the course of the year. The public should rest assured that we will continue to refine our approach towards criminal justice, with the view to ensuring that no misconduct goes unpunished, that all misconduct is justly punished, and that all persons are equally treated before the law.”(4) TYL Looseleaf at (703) – (800). |

| ↑47 | See for example, PP v Lai Teck Guan (2018) 5 SLR 852 (SGHC) at (37) and (42) where the Court found that the Vasentha sentencing bands for first-time offenders of trafficking diamorphine was not suitable for repeated offences by way of applying a mathematical uplift, but nonetheless found the Vasentha sentencing bands useful for an indicative uplift which the Court used to then create new sentencing bands for repeated offenders. |

| ↑48 | See for example, Ghazali bin Mohamed Rasul v PP (2014) 4 SLR 57 (SGHC) at (50) where the Court compared the sentences of offences of similar criminality. |

| ↑49 | See for example, Loo Pei Xiang Alan v PP (2015) 5 SLR 500 (SGHC) at (17) where the Court found it possible to derive a “conversion scale” or “exchange rate” between trafficking diamorphine and trafficking methamphetamine for sentencing. |

| ↑50 | See for example, K Saravanan Kuppusamy v PP (2016) 5 SLR 88 (SGHC) at (4) where the Court appreciated the nuanced differences between the structure of the prescribed punishments for importation versus trafficking under MDA but decided to proceed without distinction in their sentences because they have the same overall tenor. |

| ↑51 | See CHT Speech 2014 at (14); for the importance of incremental approach to sentencing see for example PP v Tan Kok Ming Michael and other appeals (2019) 5 SLR 926 (SGHC) at (104) where the Court declined to develop a sentencing framework, and instead, at (105) the Court drew upon existing case precedents to apply to the case at hand: “In line with the many sentencing precedents, I would adopt the approach of articulating, developing and clarifying the categories and factors for consideration by sentencing courts.”; Liew Zheng Yang v PP (2017) 5 SLR 1160 (SGHC) at (9) – (12) where the Court declined to develop a sentencing framework, and at (16) adopted the incremental approach: “Therefore I would approach the sentencing of this case in the usual way by examining the aggravating and mitigating factors which are germane to the charge of possession for the purpose of his own consumption, keeping in mind the existing sentencing precedents”; Takaaki Masui at (78); YL Looseleaf at (804) on p XVII 253 – 254 and (805) on p XVII 255 – 256. |

| ↑52 | See Benny Tan 2018 at 1047 at (74). |

| ↑53 | See Benny Tan 2018 at 1060 at (1); see also DJ Shawn’s Article, where the article had identified Poh Boon Kiat and Koh Yong Chiah and Vasentha as falling within the “two-step sentencing bands” approach even though Terence Ng had identified those cases as falling under other approaches. |

| ↑54 | CHT Speech 2014 at (14). |

| ↑55 | This perhaps explains why the Court of Appeal’s general observation of sentencing approaches in (133) of PP v ASR (2019) 1 SLR 941 (SGCA) below, is quintessentially congruent with the substantive technique or spirit of the “five-step sentencing bands” approach: “Part of the reason why retribution may be “displaced” in this way is because it is hard to say with absolute quantitative precision what an offender deserves for his crime. That is why, where a sentencing framework is in play, the general practice is that the court first identifies the appropriate sentencing range on the basis of the harm caused and the offender’s culpability, and then, having regard to other sentencing factors, including outcome-focused sentencing objectives, chooses the appropriate sentence within that range. The range operates as a margin of reasonableness which ensures that the eventual sentence imposed remains broadly proportionate to the crime…” |