Read a Good Book Lately?

We asked lawyers to recommend books that have resonated with them and share why they think a particular book is special. Read these “mini reviews” and add these titles to your reading list!

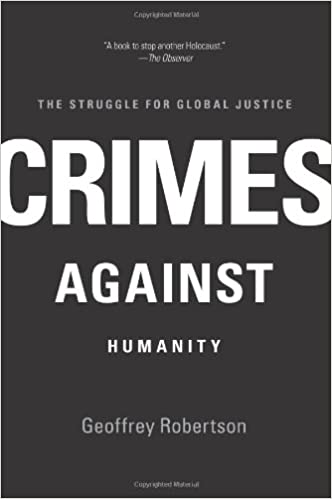

Crimes Against Humanity: The Struggle for Global Justice is now on its third edition, published in 2006 by Penguin Books with new, updated material. Its author, Geoffrey Robertson KC, is a celebrated criminal defence barrister who was conferred Australian Humanist of the Year 2014 for his work as a human rights lawyer and advocate. He is a prolific author, and Crimes Against Humanity has been described as “an epic work” by The Times (London).

Epic it is. Depending on the edition you hold, the tome runs into anywhere between 658 to 1000 pages, densely packed with information and meticulously referenced. And though Robertson may also be an academic and educator, this is by no means a textbook. Robertson’s personality cuts through every page of this work, where he offers his critical view of the actions (and in many cases, inaction) of international actors, leaders and human rights bodies. This is refreshing in a genre where many others hold back their criticisms for fear of reprisals – it is apparent that Robertson is unencumbered by such blasé considerations.

The result is a book that is informative yet critical, and therefore excellent whether as a first introduction to the subject or as an addition to the collections of those already familiar with the genre. Robertson starts with the trial of Charles I in 1649 as the first rejection of sovereign immunity as a blanket answer to accusations of war crimes. Charles had famously refused to recognise the authority of the tribunal over him – but this was not enough to save his head from the execution block. We do not dwell in early modern history for long, moving quickly to the Nuremberg trials, still regarded as the most important milestone in international human rights law. Significant as it may be, Robertson is nonetheless critical of aspects of the trials, offering his views on how the Allies could (and should) have led a lot better by example in their conduct of them. He then continues to trace other developments post-Nuremberg, including events in Chile, the Balkans, Kosovo and Iraq.

Closer to home, Robertson offers a cogent argument against the death penalty (in particular, the mandatory one) alongside critcisms of Lee Kuan Yew and “Asian values” as a justification for eroding individual liberties.

All in all, the book carries an important message – will the international community continue to turn a blind eye to atrocities, or is it time for us to consider it our duty to stop atrocities where they happen? The answer appears obvious, but inertia seems to be a great force. The recent Russian invasion of Ukraine is a case in point – it would be interesting if Robertson were to update this book with his analysis.

Chooi Jing Yen

Partner

Eugene Thuraisingam LLP

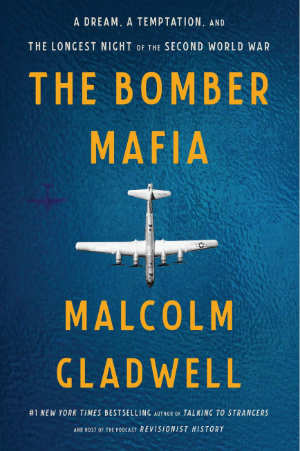

Malcolm Gladwell has the innate ability to juxtapose and weave uncanny facts, sometimes with liberal self-interpretation. Its arguable that some of The Bomber Mafia fits squarely into this categorisation. But there is absolutely no detracting the tight script, engaging and compelling manner in which he writes. This latest book is no exception.

Gladwell opens the book with Carl Norden and the dream of creating the most accurate bombsight which could be mounted in a bomber. Gladwell doesn’t dwell on the horrors or futility of war as we know it, which is itself evident. He instead interposes the storyline of the bombsight and technological advances with the countervailing theories of area bombing as opposed to target-specific bombing. Each has its own consequences. Would the former break the will of a besieged population? Or would greater impact be taking out specific targets such as a munitions factory or runway? In this connection he masterfully narrates the ideological differences between Generals Curtis LeMay and Haywood Hansell as instrumental characters in the book who vividly come to life in the pages. In between it all is the creation of the Air Corps Tactical School, the leaders of whom were labelled the “Bomber Mafia” – Proficimus more irretenti (we make progress unhindered by custom).

We are given an insight as to historical context and how the air force and its tactics were influenced from the American and Allied sides. Of particular interest is the role Frederick Lindemann (later Lord Cherwell), an intellectual of brilliance and eccentricity, had on Winston Churchill. We are introduced to the concept of “transactive memory” where memories are not just stored in our being and mind, but also those of people we love – you don’t have to remember how to work the remote because you know your daughter will for instance. Churchill stores all his thinking in the quantitative and immense world inside Lindemann’s mind, which opined to indiscriminately bomb cities to break the will of people. Which in turn affected the British bombing command and how it conducted its own raids.

The nuances are wonderfully itemised. Gladwell’s book is well researched and quite simply, extremely readable. It gives perspective to the course of the Second World War from an aerial perspective, what the possibilities could have been in each facet and the central question which is really – how humanity perceives war and life in equal measure. I enjoyed every page.

Zaheer K. Merchant

Director

QI Group of Companies

The Rule of Law, written by Senior Law Lord Thomas Bingham, weighs (at Part I) in on the hefty topic of the Rule of Law, beginning from its underpinnings in the Magna Carta, and then to the Rule of Law’s first proponent, A V Dicey. Part II of the book covers some of the main themes (such as “Law not discretion”), albeit not all, of which we have come to expect of the Rule of Law (not to be confused with “rule by law”), and to my mind, carries some of the essence of what is meant by the Rule of Law. Part III of the book deals with the application of the Rule of Law to terrorism and parliamentary sovereignty, which is more nuanced and contextualized within the landscape in the United Kingdom.

I commend this book to the reader, including those who are not versed in law, not only for the content bearing on the monumental subject matter, but because of the quality of the writing. It is classic English writing at the simplest best.

Glen Koh

Advocate and Solicitor

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind is a book on the biological and societal evolution of our species, the homo sapiens, by Yuval Noah Hariri.

Sapiens purports to explain the origin of virtually all major aspects of humanity — religion, human social groups, and civilization — in evolutionary terms. The book is well-written, sensible, engaging, and thought provoking.

Regardless of what you believe in, it will spark an internal awareness of where the human race has come from and where it may be headed towards. Don’t be distracted by many negative reviews on Hairiri or the book itself. If you enjoy history and science, you’ll appreciate the manner he has coalesced 10,000 years of human evolution into about 450 pages. It’s the sort of book that puts many things in perspective. Chapters 14 to 17 are compelling.

It is available at NLB as a physical book, ebook, and audiobook.

Anil N Balchandani

Red Lion Circle

I started reading Tolstoy’s War and Peace when I was a 15-year-old student. It took me about two years to finish it, since it was so long and epic! Since then, I became fascinated with the life of Leo Tolstoy himself and looked forward to reading his other works. However, I got around to reading this only in the beginning of 2022, when my psychologist daughter kindly helped load some books, including the 800-page Anna Karenina into my Kindle. It took me about six months of nightly bed-time readings to reach the last page of this long novel.

This turned out to be a most timely read indeed. Little did I realise then that in January 2022 the Russia-Ukraine war would break out soon. Many of the events in the book are set in the towns and countryside of Russia, including some parts which are in present-day Ukraine.

The themes in this great novel are matters such as relationships, family, marriage, desire and betrayal; as well as the lifestyles of the aristocracy, high society and workers in Russia at that time, set against the early spring of socialist ideas and the emancipation of women. It features several colourful protagonists, including the elegant but tempestuous Anna herself (a woman ahead of her time), the professional soldier Vronsky, the troubled intellectual Levin (whose traits are modelled after Tolstoy himself) and a host of various inter-connected characters with their own little universes and aspirations.

What stood out for me most in this novel is my observation of how little life has changed in essence in urban life between that time, i.e. the 1880s in Russia and 21st-century “still capitalist” societies. For example, save for the difference in technology, the calling for sledges for hire when the socialites leave a soiree on late winter nights is not very different from how one would call for a late night taxi nowadays. On a larger note, also comparable are the scenes in Russian high life at that time with pages from the Tatler now; the pseudo-intellectual and political discussions over drinks and cigars of that time still continue today; and the tensions between the rich aristocracy and the rights of workers then still goes on today in most societies. Also noteworthy is how little the conversations between married couples and lovers back then in Russia were not much different from the kinds of conversations one will find in American and Asian television sitcoms nowadays. How little human behaviour changes through the ages!

To me those observations of urban life were more interesting than the tragic and comic melodrama, intrigues and emotions of the main characters, which Tolstoy wrote about so masterfully. The novel has been made into hundreds of movies, operas, ballets and television series in various languages. I have since watched some on Netflix to help me better understand some bits of the complex side-plots in the novel.

Naresh Mahtani

Director

Adelphi Law Chambers LLC

Zen and the Art of Mediation is a book by Martin Plowman which brings two disciplines, Zen and Mediation to the discerning attention of the reading world once again. Zen is a Buddhist philosophy that emphasises meditation for direct enlightenment. Mediation as an alternative dispute resolution system has been in vogue in the legal market for many years and chooses to be ever increasingly popular in the commercial world of today. Putting further “icing” on the mediation “cake” the writer (both a mediator and Zen practitioner) very compellingly persuades us to take up mediation over litigation as the doable in dispute resolution.

Content-wise, the writer gives valuable perspectives and take-aways on how best to approach mediation. For the legal practitioner, the book is substantially on mediation, though the titular reference to Zen. Also, the writer promises early in the book, of non-adherence to religious dogma. References to Zen wisdom are in the context of how it can be applied (with a certain mindset) to dispute resolution and also in emphasising the helpfulness or practicality of following such wisdom when approaching mediation (for the writer). However, the writer does encourage the reader to meditate (this is explained in one of the chapters), but it ends there. There is no advice on how to burn incense or recite sutras. (Anyway, Zen as a spiritual practice is not dependent on any canonical scripture.)

So, Zen and the Art of Mediation is a book that is recommended for the legal practitioner, particularly those involved in dispute resolution. The writer has shared many of his own substantial practice experiences in mediation while writing the book – with an added emphasis on what not to do in mediation. The book was published in 2019 and is available both in Kindle and Paperback editions at online Amazon.com. The customer reviews are good – 4.6 out of 5 and the book is affordable.

For young lawyers, the book is a good headstart. For veterans, with a dollop of mediation accumulated over the years and being experts in their own right, may want a break and venture into other books on Zen as well. If so, Zen in the Art of Archery or Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance is recommended. With that, if you do get a copy of Zen and the Art of Mediation, experience the bliss of Meditation and Mediation, all – in all!

K Ravendra

Director

Vision Law LLC

A couple more fresh reads for 2023

1. Oliver Roeder, Seven Games

You will likely have played one or more of the seven games covered in this book – checkers, chess, go, backgammon, poker, scrabble and bridge. But how well do you know the history of each game and how they have evolved with the proliferation of information and the rise of AI? Oliver Roeder’s Seven Games offers fascinating insights into what games are, why games are special and the unique strategies of each game. As the author suggests, if games are about overcoming unnecessary obstacles, life is also a game after all?

2. Barack Obama, A Promised Land

Former US President Barack Obama provides in his memoir A Promised Land an immensely personal and frank rendering of the first term of his presidency (and the events leading up to it – remember “Yes We Can”?). You cannot help but be drawn into the cauldron of US domestic politics and international relations, revealing deep-rooted tensions which continue to resonate in today’s complex world. Obama’s account of the assassination of the most feared terrorist in 2011 reads like a thriller and dissects the art of making difficult decisions.

3. The Secret Barrister, Nothing But the Truth

The hard truth of what lawyering entails in reality emerges from the numerous vignettes of the life of a junior English barrister specialising in criminal law. This is in fact The Secret Barrister’s third book. You do not need to be a lawyer to empathise with the author’s ordeals of “the daily grind” of legal practice. Besides the humorous anecdotes, Nothing But the Truth delves into the role of lawyers and thorny issues on criminal justice. It is a gritty, no-holds-barred book that gives readers an opportunity to reflect on “crime, guilt and the loss of innocence”, and reminds all of us of the good but often unappreciated work that lawyers do.

4. Matthew Ball, The Metaverse: And How It Will Revolutionize Everything

If you have not heard of the metaverse in 2022, where have you been? The most talked-about revolutionary concept of the “next Internet” may have already arrived. In The Metaverse, Matthew Ball provides a solid foundation for the uninitiated into the inner workings of the metaverse. Lawyers will no doubt zoom in on the detailed working definition of the metaverse that he uses to develop his vision for the future. If you are not already into Fortnite or the Legend of Zelda, turn to The Metaverse to understand what all the fuss is about, and how the metaverse is likely to transform the economy and society.

5. Haruki Murakami, Novelist as a Vocation

Writing novels may not be your dream job, but there is much that you can apply to your day job from Japanese author Haruki Murakami’s disciplined approach as a professional writer. No pre-requisite of reading any of Murakami’s well-known novels is necessary for this masterclass. You will be surprised at how much ground he covers in exploring topics such as originality and how he writes his novels. As Murakami candidly admits, there is no universal success formula here, although he emphasises that intrinsic motivation and “mental toughness” are needed to sustain a writing vocation over the long haul. Sounds like good advice for staying and surviving in any other profession, and a good model for all types of writers.

Alvin Chen

Chief Legal Officer and Director, Representation and Law Reform

The Law Society of Singapore